Poetry Review – Under a Giant Sky: Richie McCaffery welcomes the British publication of a substantial body of work by Toon Tellegen, translated from the Dutch by Judith Wilkinson

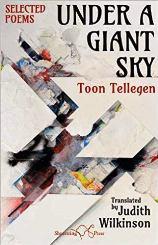

Under a Giant Sky

Toon Tellegen (translated by Judith Wilkinson)

Shoestring Press, 2019

ISBN: 978-1-912524-44-0

258 pp £15.00

Under a Giant Sky

Toon Tellegen (translated by Judith Wilkinson)

Shoestring Press, 2019

ISBN: 978-1-912524-44-0

258 pp £15.00

We don’t see nearly enough Dutch and Flemish language poetry in English translation and so it’s a cause for celebration to welcome Judith Wilkinson’s sizeable selection (240 pages) of her translations of the prolific output of Toon Tellegen, a doyen of Dutch poetry. The UK seems to have a curious cultural blind-spot when it comes to the art and writing of the Low Countries, often the butt of so many trite jokes that fall wide of the mark. But perhaps the tide is slowly beginning to turn at this most unlikely time of nationalistic isolationism. 2018 saw the publication by Carcanet of Paul Vincent’s translations of the poems of Belgian poet Leonard Nolens (An English Anthology) and 2019 gave rise to this title presently under review. We can only wonder what indispensable voice might be made available to us this Brexit year.

What is particularly striking about the sheer scale of Judith Wilkinson’s project to make a hefty tranche of Tellegen’s poetry available to us in English is that, chronologically arranged as it is, we get to see that he is a poet who seems to have emerged with his own distinctive quizzical voice and style fully formed. This is not to say that Tellegen hasn’t developed emotionally and aesthetically as he has grown older; but he seems to have hit upon a winning formula early and continues to interrogate the world and its inhabitants in his own quirky and wry way. Thematically and stylistically he reminds me of the Scottish poet Norman MacCaig, who, after writing poems in a neo-Romantic / Apocalyptic style in the 1940s that he then disowned, subsequently discovered a zen-like scepticism and a type of poem that stayed with him all his creative life. He only wrote one particularly long poem – ‘A Man in Assynt’ – and on the evidence of Under a Giant Sky, Tellegen only has one long poem in the form of ‘A Poem for Henry Hudson’. Like MacCaig’s poems, Tellegen’s seem to strive for a cosmic balance, as if very weighty subjects are always being assessed and kept in check by the verse. In ‘The Flower’ the mystery of the meaning of existence is lost in the cyclical power of nature, the poem itself acting almost as a mandala in words:

What should I do with my summer, the flower wonders.

Blossom! (…)

And with my autumn? Wilt! (…)

(…)

And with my winter, the flower wonders,

what should I do with my winter?

Tellegen’s power as a master minimalist, too, cannot be underestimated. He tries to make few words count in an age where they are almost unthinkingly and meaninglessly squandered. ‘One Swallow’ is all of five short lines and nineteen words long and goes like this:

You,

you were a swallow,

the first swallow,

and you made seven summers

without a single winter in between.

Tellegen’s typical poem is brief and understated with minimum scenery and background noise, interference or ornamentation. It is also often universally non-specific, except for occasional references to actual places like the Mariana Trench. At first what seems like a disarmingly simple, almost child-like poem or idea lulls the reader into false security. The rug on which the complacent reader stands is quickly pulled away and formulaic responses or thoughts (a bugbear of MacCaig too) are totally inverted or shown to be in some way bogus or absurd. In ‘Sleeping Beauty’ the stock legendary princess we all know about instead leaves a note instructing the prince that she’s not to be kissed awake under any circumstances. We’ve all heard of the fable of the emperor’s new clothes, but in Tellegen’s ‘The Emperor’ he is fully aware he’s naked and is playing a trick on his subjects. In ‘The Garden’, the lawn is suddenly personified and it tells us in no uncertain terms that it wishes to be neglected, is sick of being fussed with and altered by people. The poems themselves are often populated with binary oppositions: yes and no, day and night, leaving and staying, the self and the other:

I wanted to make the impossible possible.

I loved the impossible, loved nothing more passionately,

but I still wanted to make it possible,

(…)

but years later, when I wanted to make the possible impossible,

someone cried that I should hurry up and come inside,

why was I dilly-dallying like that,

there was still so much to do.

(from ‘The Impossible’)

Another recurrent tactic deployed by Tellegen is paralepsis, that is to say that his poems often hold their hands up and explicitly say ‘I am not going to talk about x’ and then all they talk about is x via negation. This is particularly evident in ‘On Death’ where the speaker insists they ‘don’t want to talk about death any more’ to such a degree that all the poem is therefore about is death. It is Tellegen’s unfaltering eye for the absurd in life and language that elevates these poems to high-art. In these poems people do not call or cry or shout for war, but whisper (‘The One Wants Peace’). He writes a sort of quietly subversive poetry that is often unheard in a vociferous world. Compare, for instance, Norman MacCaig’s poem ‘Power dive’, where some grotesque plutocrat is about to jump into his new swimming pool:

It was just before he hit the water

in his first dive that he glimpsed

the triangular fin cutting the surface.

with that of the anonymous ‘everyman’ figure in Tellegen’s ‘The Man’:

How elegantly he dives off a board into the wintry pool.

(…)

but time has stopped for him, for him alone.

He’s been suspended in mid-air for years,

stretched out, heading straight down.

MacCaig’s poem is witty, invites the reader to chuckle, Tellegen’s stops the reader in their tracks with a rather troublingly existential image. Quite often Tellegen breaks down the wall between reader and poet, as in ‘A Letter’ where we’re told that ‘you’ll never be able to find me / if you don’t read this’. The problem is that although many of the poems have the presence of a first person narrator, it is that of a puckish narrator who enjoys playing tricks and is always slightly beyond easy reach. In ‘A Wadeable Place’ we’re given warning that these poems might seem shallow and light at first, like the edge of a lake, but they’re also dangerous zones. The poems regularly defy simply conclusions, linear story-lines or even logic itself as we (mis?)understand it. In ‘Flying Backwards’ the speaker dreams of being able to fly backwards (a leitmotif that runs through much of Tellegen’s poetry) only to be told that it’s impossible:

No, she said, with strange anger, it is forever impossible.

And I went on flying, backwards,

with broad, long strokes.

In ‘Wings’ the speaker takes off and flies away in search of the wings they lack and yearn for. There is much subtly unsettling humour in Tellegen’s poems but there’s much more to them than that. In the midst of absurdity there is also much pain and pathos. There is a lost family that haunt these poems, dead brothers, a father who lived a life of quiet desperation and a long-suffering mother:

In the Museum of Domestic Bliss

I saw the famous shards.

But when I asked after the Mother,

the attendant gave me a grave look.

She’s temporarily on loan elsewhere, he said.

In lexically playful poems like ‘When I Wanted to Write to You’ the poet finds that some words in his vocabulary are missing, such as ‘not’ and so the poem becomes a search in material space for that lost word and the concept it conjures up. When you begin to realise that in Tellegen’s sometimes dreamlike world anything is possible ‘under a giant sky’ you begin to warm to his unique and often disconcertingly ludic style where the conceptual becomes physical and vice versa, where the past closes itself like a door (‘A Man Walked and Became a Skeleton’).

I noticed many echoes of the work of other poets while reading this book, which I see as a good sign. For example, in ‘The Discovery’ a man discovers the meaning of life and it plunges people into utter panic, perhaps reminding the reader of Philip Larkin’s ‘Days’. And it is days like these where we need more poetry in translation, especially from overlooked European allies such as the Netherlands. To be reminded of poets from a native canon of work by the writings of a poet operating in another language and tradition is to prove that there is much more that unites us than divides us.

Feb 20 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Toon Tellegen

Poetry Review – Under a Giant Sky: Richie McCaffery welcomes the British publication of a substantial body of work by Toon Tellegen, translated from the Dutch by Judith Wilkinson

We don’t see nearly enough Dutch and Flemish language poetry in English translation and so it’s a cause for celebration to welcome Judith Wilkinson’s sizeable selection (240 pages) of her translations of the prolific output of Toon Tellegen, a doyen of Dutch poetry. The UK seems to have a curious cultural blind-spot when it comes to the art and writing of the Low Countries, often the butt of so many trite jokes that fall wide of the mark. But perhaps the tide is slowly beginning to turn at this most unlikely time of nationalistic isolationism. 2018 saw the publication by Carcanet of Paul Vincent’s translations of the poems of Belgian poet Leonard Nolens (An English Anthology) and 2019 gave rise to this title presently under review. We can only wonder what indispensable voice might be made available to us this Brexit year.

What is particularly striking about the sheer scale of Judith Wilkinson’s project to make a hefty tranche of Tellegen’s poetry available to us in English is that, chronologically arranged as it is, we get to see that he is a poet who seems to have emerged with his own distinctive quizzical voice and style fully formed. This is not to say that Tellegen hasn’t developed emotionally and aesthetically as he has grown older; but he seems to have hit upon a winning formula early and continues to interrogate the world and its inhabitants in his own quirky and wry way. Thematically and stylistically he reminds me of the Scottish poet Norman MacCaig, who, after writing poems in a neo-Romantic / Apocalyptic style in the 1940s that he then disowned, subsequently discovered a zen-like scepticism and a type of poem that stayed with him all his creative life. He only wrote one particularly long poem – ‘A Man in Assynt’ – and on the evidence of Under a Giant Sky, Tellegen only has one long poem in the form of ‘A Poem for Henry Hudson’. Like MacCaig’s poems, Tellegen’s seem to strive for a cosmic balance, as if very weighty subjects are always being assessed and kept in check by the verse. In ‘The Flower’ the mystery of the meaning of existence is lost in the cyclical power of nature, the poem itself acting almost as a mandala in words:

Tellegen’s power as a master minimalist, too, cannot be underestimated. He tries to make few words count in an age where they are almost unthinkingly and meaninglessly squandered. ‘One Swallow’ is all of five short lines and nineteen words long and goes like this:

Tellegen’s typical poem is brief and understated with minimum scenery and background noise, interference or ornamentation. It is also often universally non-specific, except for occasional references to actual places like the Mariana Trench. At first what seems like a disarmingly simple, almost child-like poem or idea lulls the reader into false security. The rug on which the complacent reader stands is quickly pulled away and formulaic responses or thoughts (a bugbear of MacCaig too) are totally inverted or shown to be in some way bogus or absurd. In ‘Sleeping Beauty’ the stock legendary princess we all know about instead leaves a note instructing the prince that she’s not to be kissed awake under any circumstances. We’ve all heard of the fable of the emperor’s new clothes, but in Tellegen’s ‘The Emperor’ he is fully aware he’s naked and is playing a trick on his subjects. In ‘The Garden’, the lawn is suddenly personified and it tells us in no uncertain terms that it wishes to be neglected, is sick of being fussed with and altered by people. The poems themselves are often populated with binary oppositions: yes and no, day and night, leaving and staying, the self and the other:

I wanted to make the impossible possible. I loved the impossible, loved nothing more passionately, but I still wanted to make it possible, (…) but years later, when I wanted to make the possible impossible, someone cried that I should hurry up and come inside, why was I dilly-dallying like that, there was still so much to do. (from ‘The Impossible’)Another recurrent tactic deployed by Tellegen is paralepsis, that is to say that his poems often hold their hands up and explicitly say ‘I am not going to talk about x’ and then all they talk about is x via negation. This is particularly evident in ‘On Death’ where the speaker insists they ‘don’t want to talk about death any more’ to such a degree that all the poem is therefore about is death. It is Tellegen’s unfaltering eye for the absurd in life and language that elevates these poems to high-art. In these poems people do not call or cry or shout for war, but whisper (‘The One Wants Peace’). He writes a sort of quietly subversive poetry that is often unheard in a vociferous world. Compare, for instance, Norman MacCaig’s poem ‘Power dive’, where some grotesque plutocrat is about to jump into his new swimming pool:

with that of the anonymous ‘everyman’ figure in Tellegen’s ‘The Man’:

MacCaig’s poem is witty, invites the reader to chuckle, Tellegen’s stops the reader in their tracks with a rather troublingly existential image. Quite often Tellegen breaks down the wall between reader and poet, as in ‘A Letter’ where we’re told that ‘you’ll never be able to find me / if you don’t read this’. The problem is that although many of the poems have the presence of a first person narrator, it is that of a puckish narrator who enjoys playing tricks and is always slightly beyond easy reach. In ‘A Wadeable Place’ we’re given warning that these poems might seem shallow and light at first, like the edge of a lake, but they’re also dangerous zones. The poems regularly defy simply conclusions, linear story-lines or even logic itself as we (mis?)understand it. In ‘Flying Backwards’ the speaker dreams of being able to fly backwards (a leitmotif that runs through much of Tellegen’s poetry) only to be told that it’s impossible:

In ‘Wings’ the speaker takes off and flies away in search of the wings they lack and yearn for. There is much subtly unsettling humour in Tellegen’s poems but there’s much more to them than that. In the midst of absurdity there is also much pain and pathos. There is a lost family that haunt these poems, dead brothers, a father who lived a life of quiet desperation and a long-suffering mother:

In lexically playful poems like ‘When I Wanted to Write to You’ the poet finds that some words in his vocabulary are missing, such as ‘not’ and so the poem becomes a search in material space for that lost word and the concept it conjures up. When you begin to realise that in Tellegen’s sometimes dreamlike world anything is possible ‘under a giant sky’ you begin to warm to his unique and often disconcertingly ludic style where the conceptual becomes physical and vice versa, where the past closes itself like a door (‘A Man Walked and Became a Skeleton’).

I noticed many echoes of the work of other poets while reading this book, which I see as a good sign. For example, in ‘The Discovery’ a man discovers the meaning of life and it plunges people into utter panic, perhaps reminding the reader of Philip Larkin’s ‘Days’. And it is days like these where we need more poetry in translation, especially from overlooked European allies such as the Netherlands. To be reminded of poets from a native canon of work by the writings of a poet operating in another language and tradition is to prove that there is much more that unites us than divides us.