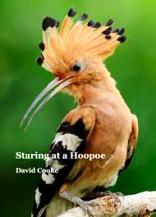

Poetry Review – Staring at a Hoopoe: William Bedford considers the interplay of appearance and reality in a new collection by David Cooke

Staring at a Hoopoe

David Cooke

Dempsey & Windle 2020

ISBN 9781913329082

£10.00

Staring at a Hoopoe

David Cooke

Dempsey & Windle 2020

ISBN 9781913329082

£10.00

In David Cooke’s new collection, Staring at a Hoopoe, there is an encounter between an old man whose eyes ‘are stoical,/but lit by a sense/that all is not determined’ and the eponymous hoopoe ‘whose piping/mnemonic call/is like a final summons’. ‘Caught in the moment’, we are told in an epigraph from Montale that this ‘joyful, slandered bird’ is ‘ambivalent’, though whether this is the bird’s view or the poem’s isn’t clear. Some form of ‘final summons’ is common to both bird and man.

The details of experience are at the heart of Staring at a Hoopoe – as with much of Cooke’s work – the poet constantly finding deeper meanings in those details. In ‘The Magus,’ for instance, there are hints of Aristotelean arguments about substance and accidence, but also modern epistemology asking whether ‘tables and chairs are clouds of atoms’, ‘glass is merely an icy river?’ ‘Such things are merely tokens’, the poem tells us, and yet the Magus ‘sees through them’ ‘with the warmth of a memory,/released in a whisper of butterflies’ wings’. The answer is clearly in that final whisper of wings.

In ‘Swallow,’ the details of flight are exact – ‘Heels raised,/arms stretched’ – though whether the poem is talking about a bird or a girl is deliberately unclear. What is clear, is that in flight

she breasts

the air,

craving its pull

a shift

in the elements

that may one day

release her.

Again, in ‘Swimmer,’ the detail is clear but the hint of something beyond the detail explicit: ‘Parting the water, he leaves/no trace beyond a brief ripple’ until at the end of the poem ‘There is only/ distance now between him/and the point he dreams of’. In a way, as in ‘Soul,’ this is all about ‘simple lyrics/ that told the truth’, though the truth is never simple, and often wordless, as in the jazz music that Cooke frequently uses as an analogy. ‘The Way Art Pepper Tells It’ is a fine example, the musician ‘Reinventing where he’s been,/ one shimmering note/at a time’, though finally ‘the way ahead’s unclear’, reminding us of the volume’s epigraph from Kierkegaard: ‘Life is understood backwards, but has to be lived forwards.’ That ‘forwards’ is inevitably to death, but even in ‘In Père Lachaise Cemetery,’ ‘The Sparrow’s voice still resonates beyond/each tragic circumstance’.

The traveller, archaeologist, linguist and cartographer Gertrude Bell provides the inspiration for a sequence – From Middlesbrough to Mosel – half-way through Staring at a Hoopoe. ‘The Bell Maps Have Shown the Way’ tells us ‘An accurate map denotes a journey,’ a familiar form of allegory. For Bell herself, the journey was into the unknown in every sense:

Her path at first was vague

from where she stood, and who

she was, towards whatever she might be,

the myth she represents.

In ‘Father and Daughter,’ there is still love despite the failure of understanding, the ‘eight-year-old tomboy’ growing up into the woman who ‘will send/ her soothing letters’ from ‘far-flung Arabia,’ letters which will ‘speak of all the things/ he can bear to know.’ The stepmother in ‘Florence’ tries ‘her best’ to school the father’s children, but ‘couldn’t curb his talented girl,/ who read much more than a daughter needs to/ and piped up insufferably’. Once at Oxford, the talented girl in ‘A Bluestocking’ clearly found it difficult to conform, quick to say ‘I disagree’, finding her way at last in Persian, where

the word for “paradise”

is intertwined with “garden”, just as soul

and body are in the poetry of Hafiz.

In her friendship with T.E. Lawrence, she ‘galloped like a man/in freedom and comfort across the dunes,’ only coming to defeat in ‘Old Maid’ in a love affair with a married man: ‘Self-assured and strident/ in so many ways,/ she couldn’t face “adultery”’. This seems a sad ending to a life of such courage, the sequence ending with ‘Iraqi Schoolgirls, 1932,’ where ‘who can say/ what they’ll make of these things they learn – / their lives safe and circumscribed,/ their lips scarcely moving?’ There is a great feminist irony here.

‘Why fret to save the appearances?’ ‘The Magus’ asks, and perhaps that is because ‘description is revelation’ as Wallace Stevens tell us in ‘Found.’ It continues to be true in the third part of Staring at a Hoopoe. There is also imagination. In ‘Two Rooms: after Van Gogh,’ closed walls ‘collapse’ and then:

All that remains is a window

that you will slowly fill with bridges,

boats, faces, trees; some yellow, white

or purple flowers; the endless waves

of a cornfield above which a handful

of wind-tossed birds

seem to be holding their own.

And again, ‘where a man sits alone/on a simple chair’, sensing ‘beyond the flames of manic summers/that cold stars are turning,/tuned to a shrill monotonous note.’ In ‘Sassy,’ both jazz and the music beyond jazz perform their mysterious effect, a girl who ‘could swear/like one of the boys/her mouth foul/as any sailor’s’ is

Scatting hard

across the octaves,

her voice

like a horn

swapping licks

with bop’s elite:

One step ahead

of the changes,

she harnessed time

as if she owned it

in pitch-perfect

glissandos.

Most cleverly, Staring at a Hoopoe ends with ‘Man on a Wire,’ which might be said to describe how Cooke has handled his task to ‘save the appearances’. When our high-wire artist

looks back on his life

he will see that the best of it

was a journey he took from A to B

above a world of chairs

and carpets, dates and deliveries,

or the cops who stared amazed

at a man walking across the sky

This seems to me to be poetry going on a wonderful journey.

Feb 13 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – David Cooke

Poetry Review – Staring at a Hoopoe: William Bedford considers the interplay of appearance and reality in a new collection by David Cooke

In David Cooke’s new collection, Staring at a Hoopoe, there is an encounter between an old man whose eyes ‘are stoical,/but lit by a sense/that all is not determined’ and the eponymous hoopoe ‘whose piping/mnemonic call/is like a final summons’. ‘Caught in the moment’, we are told in an epigraph from Montale that this ‘joyful, slandered bird’ is ‘ambivalent’, though whether this is the bird’s view or the poem’s isn’t clear. Some form of ‘final summons’ is common to both bird and man.

The details of experience are at the heart of Staring at a Hoopoe – as with much of Cooke’s work – the poet constantly finding deeper meanings in those details. In ‘The Magus,’ for instance, there are hints of Aristotelean arguments about substance and accidence, but also modern epistemology asking whether ‘tables and chairs are clouds of atoms’, ‘glass is merely an icy river?’ ‘Such things are merely tokens’, the poem tells us, and yet the Magus ‘sees through them’ ‘with the warmth of a memory,/released in a whisper of butterflies’ wings’. The answer is clearly in that final whisper of wings.

In ‘Swallow,’ the details of flight are exact – ‘Heels raised,/arms stretched’ – though whether the poem is talking about a bird or a girl is deliberately unclear. What is clear, is that in flight

Again, in ‘Swimmer,’ the detail is clear but the hint of something beyond the detail explicit: ‘Parting the water, he leaves/no trace beyond a brief ripple’ until at the end of the poem ‘There is only/ distance now between him/and the point he dreams of’. In a way, as in ‘Soul,’ this is all about ‘simple lyrics/ that told the truth’, though the truth is never simple, and often wordless, as in the jazz music that Cooke frequently uses as an analogy. ‘The Way Art Pepper Tells It’ is a fine example, the musician ‘Reinventing where he’s been,/ one shimmering note/at a time’, though finally ‘the way ahead’s unclear’, reminding us of the volume’s epigraph from Kierkegaard: ‘Life is understood backwards, but has to be lived forwards.’ That ‘forwards’ is inevitably to death, but even in ‘In Père Lachaise Cemetery,’ ‘The Sparrow’s voice still resonates beyond/each tragic circumstance’.

The traveller, archaeologist, linguist and cartographer Gertrude Bell provides the inspiration for a sequence – From Middlesbrough to Mosel – half-way through Staring at a Hoopoe. ‘The Bell Maps Have Shown the Way’ tells us ‘An accurate map denotes a journey,’ a familiar form of allegory. For Bell herself, the journey was into the unknown in every sense:

In ‘Father and Daughter,’ there is still love despite the failure of understanding, the ‘eight-year-old tomboy’ growing up into the woman who ‘will send/ her soothing letters’ from ‘far-flung Arabia,’ letters which will ‘speak of all the things/ he can bear to know.’ The stepmother in ‘Florence’ tries ‘her best’ to school the father’s children, but ‘couldn’t curb his talented girl,/ who read much more than a daughter needs to/ and piped up insufferably’. Once at Oxford, the talented girl in ‘A Bluestocking’ clearly found it difficult to conform, quick to say ‘I disagree’, finding her way at last in Persian, where

In her friendship with T.E. Lawrence, she ‘galloped like a man/in freedom and comfort across the dunes,’ only coming to defeat in ‘Old Maid’ in a love affair with a married man: ‘Self-assured and strident/ in so many ways,/ she couldn’t face “adultery”’. This seems a sad ending to a life of such courage, the sequence ending with ‘Iraqi Schoolgirls, 1932,’ where ‘who can say/ what they’ll make of these things they learn – / their lives safe and circumscribed,/ their lips scarcely moving?’ There is a great feminist irony here.

‘Why fret to save the appearances?’ ‘The Magus’ asks, and perhaps that is because ‘description is revelation’ as Wallace Stevens tell us in ‘Found.’ It continues to be true in the third part of Staring at a Hoopoe. There is also imagination. In ‘Two Rooms: after Van Gogh,’ closed walls ‘collapse’ and then:

And again, ‘where a man sits alone/on a simple chair’, sensing ‘beyond the flames of manic summers/that cold stars are turning,/tuned to a shrill monotonous note.’ In ‘Sassy,’ both jazz and the music beyond jazz perform their mysterious effect, a girl who ‘could swear/like one of the boys/her mouth foul/as any sailor’s’ is

Most cleverly, Staring at a Hoopoe ends with ‘Man on a Wire,’ which might be said to describe how Cooke has handled his task to ‘save the appearances’. When our high-wire artist

This seems to me to be poetry going on a wonderful journey.