Poetry Review – Jim Neat: Stuart Henson appreciates the challenges of constructing fact-based poetry such as Mary J Oliver’s biography of her father

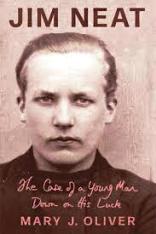

Jim Neat, The Case of a Young Man Down on His Luck

Mary J. Oliver

Seren, 2019,

ISBN 978-178-172-514-6

152pp £9.99

Jim Neat, The Case of a Young Man Down on His Luck

Mary J. Oliver

Seren, 2019,

ISBN 978-178-172-514-6

152pp £9.99

We are all migrants, to some degree – or most of us have migrant ancestry. My wife’s descended from the Huguenots, via Wales. My own great-grandfather emigrated to Canada in 1906. His first job was picking up buffalo bones from the prairie. In an age where individuals and nations have become increasingly anxious about ‘identity’, who our parents were is a source of endless fascination. Mary J. Oliver has been doing some research—a lot of research—and the result is this life of her father, Jim Neat.

The author’s characterisation of the work as a ‘long narrative poem’ is maybe a little misleading. What we’re given, in fact, is a montage of prose-poems, letters, photographs, newspaper articles and notes, which trace the story of Jim Neat’s early life, in particular his closeness to his sister, Queenie, his escape from family tensions as a stowaway to Cape Town, his subsequent journeying via Australia to Canada, his relationships and recovery from mental illness there, and his second marriage following his return to England. There are documents, too, detailing his war service in Algeria and Sicily, and several poems that explore Mary Oliver’s struggle to come to terms with his absence.

The book begins in Canada, where Jim Neat’s heart belongs. He’s ‘down on his luck’ – as the subtitle suggests – and presently an inmate of Toronto jail where he’s detained on a narcotics charge. Within two pages, though, we’re following the route that brought him to this pass, via his doctor’s case-notes and Jim’s poems, written in the Ontario hospital to which he was admitted in 1935 for psychiatric care. Like many a contemporary migrant, Jim has taken risks in his search for work, ‘riding the rods’ on freight trains, and he’s short of clothing to keep out the bitter minus temperatures.

‘We sit poking small fires, sharing stews and narcotics to numb

the pain. I must escape this brotherhood of ailing flesh. But I

need a coat. I root through a bundle of clothes in a trailer. It’s

solid…a man, already dead. I undress him.’

The crossing-out is a device used frequently in Jim’s therapeutic writing. It works well to suggest a mind still processing experience and at the edges of self-loathing. From his childhood, Jim has been a fan of Joseph Conrad, the inspiration of his early voyaging, and for this he blames his elementary school teacher Miss Thomas. De profundis, he cries out against her well-meant ignition of his imagination, and against the privations it has brought him to:

‘I cry out loud to Canada, O Canada, you promised me I’d

reap rewards, find a wife, quickly rise to fame. You asked for

migrant workers but your system’s stacked against me. From

coast to coast, I sawed spruce in freezing temperatures.

Threshed grain in heat no one could stand. Got beaten up by

bulls for riding steel rails I’d laid myself. Swept snow. Built

roads. Bridges. Buried cattle. Did my goddam best.’

At the centre of the story is the crisis that has tipped him over into what might be a severe form of depression. Its origins lie in Jim’s romantic tragedy, the loss of his soul-mate Lizbietta and their child, Mary Oliver’s Canadian half-sister, Mariya. This part of the tale is largely supplied by another ‘found’ document, Lizbietta’s diary which covers the period between April 1932, when they met in the Saskatoon bookshop where she worked, and June 1935. The diary chronicles Jim’s settlement into the Ukrainian community, and the brief period of happiness and stability he found there. The entry for ‘Sunday 25th May 1932’ is the fulcrum on which this section pivots.

‘Supper finished, dishes washed and put away, we walked down to

the river, watched the chipmunks for ages, taking the dry grass down

into their little burrows. Scrambled down the steep bank to the

sandy beach below.

Afterwards we came back to my room. ‘Best day of my life,’ he

said. Same was true for me. Jesus.’

It’s a tough existence, mitigated by love and the support of their friend, Adam, a black porter on the Saskatoon Railroad, and Valentyna and Viktor, Lizbietta’s adoptive parents. Jim is forced to seek work away from home, and it’s on his return from one of these trips that the tragedy strikes. Lizbietta, he discovers, has died in childbirth and his daughter has been taken into the local orphanage. In his grief, he rushes wildly to the Home for Unmarried Girls and Illegitimate Babies and is arrested and committed to a hospital for the insane.

His recovery is largely due to the kind ministrations of Donald Fletcher, the Superintendent of the Whitby Hospital in Ontario where the young Jim finally washes up. Dr Fletcher’s enlightened regime and the gentle company of another inmate, the veterinary scientist Frank Schofield, prove sufficient to bring Jim back to life – a new life in England, with his sisters and eventually with the author’s mother, Kate.

The closing sections are formed principally from ‘Mary J. Oliver’s Note Book’ and ‘Mary J. Oliver’s Canada Diary’. The latter is sometimes a bit on the gushy side:

‘Clocks go back an hour. Again. I can’t believe how vast this country

is.

Taxi drops me off at midnight. Lola rushes into the street. I’m

meeting my first cousin, Queenie’s first-born, Jim’s favourite niece

for whom he stole chocolate when she was six months old. Meeting

her for the first time.

We hug each other in the tree-lined avenue…’

The former contains some of the most telling poems and prose-poems of the collection, which deal with her ambiguous feelings about her dad:

‘It was his job

to give me away

Yet I wasn’t his to give

He never kissed me goodnight

never held my hand

never met me from school

never boiled me an egg’

Among the ‘Found Documents’ there’s an ‘Exchange between my father and me’ from September 1982. In his letter to Mary, Jim explains how he chose her name – after her half- sister, Lizbietta’s lost daughter.

‘…Naming you after her was my way of surviving

without her. This hasn’t diminished the love I’ve felt for you. I feel in

you I’ve loved you both, but it’s been a love I haven’t known how to

show.

I’m sure that’s hard for you to believe or understand. I could see

your isolation in the family but I was isolated myself and lacked the

knowledge, the guts, to reach out to you.

I hope you one day find a way to forgive me.’

He goes on to tell her how proud he is of her forthcoming exhibition in Glasgow and encloses some drawings of his own. ‘What do you think? Any talent to speak of?’

The reply is five lines long, thanking him for, and praising, the drawings, and advising him to avoid darkening the pencil sketches with charcoal. The outstretched hand isn’t taken. Perhaps in this tribute, published thirty-eight years later, Mary J. Oliver has found her way of forgiving.

It’s an absorbing and thought-provoking book, and one which contains far more than there’s space to summarise here. I’m left, though, with a reservation, and it’s one that Oliver herself may have anticipated in her ‘Verdict’, the last item in the collection. This is simply a quotation from Vladimir Nabokov’s The Real Life of Sebastian Knight: ‘Remember that what you are told is really threefold: shaped by the teller, reshaped by the listener, concealed from both by the dead man of the tale.’ Oliver has declared, in both her You-tube interview and in the ‘Author’s Note’ that ‘where I found gaps in his narrative I have often augmented tantalising fragments of information with imagined details…and merged some events’ and that ‘there are a few invented figures who help move the story forward.’

As with that hybrid creature the ‘docu-drama’ you’re never quite sure where the factual documentation ends and the fiction begins. That’s not to argue that a poet can’t discover truths too deep for taint through empathy, through being there in soul and spirit, but the grey hinterland can be difficult territory. I have my doubts, for instance, about the ‘Document Enclosed in Queenie’s Letter / Bliss in Cape Town, 1921’ which purports to be a letter from a sweet fourteen year old ‘sex worker’ whom Jim encountered when he stowed away at the age of fifteen. No doubt someone will contact me to explain that, no, it’s word-for-word authentic; that’s always the way. Nevertheless, once sown, the uncertainty is there. It’s an unease that emerged again, for me, at one of the key moments in the narrative. The circumstances of Lizbietta’s death are finally revealed to Mary in a letter from Serge, Valentyna & Viktor’s son, dated 5th February 2008. The shock of the discovery of her body has caused him to become mute—for the rest of his life. His written account leaves a vivid impression, but he dates the event as happening in the drought of June 1936. According to Jim’s evidence, Lizbietta’s death occurred in ’35 and Jim was already in the Whitby Hospital by then. Old men, of course, can easily make slips with dates, even if they claim their memory is ‘excellent’. The incident is so heart-rending you wouldn’t want to make it up. The reader’s already on-side with Jim Neat. His story is compelling enough without dramatic embellishment.

Feb 12 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Mary J Oliver

Poetry Review – Jim Neat: Stuart Henson appreciates the challenges of constructing fact-based poetry such as Mary J Oliver’s biography of her father

We are all migrants, to some degree – or most of us have migrant ancestry. My wife’s descended from the Huguenots, via Wales. My own great-grandfather emigrated to Canada in 1906. His first job was picking up buffalo bones from the prairie. In an age where individuals and nations have become increasingly anxious about ‘identity’, who our parents were is a source of endless fascination. Mary J. Oliver has been doing some research—a lot of research—and the result is this life of her father, Jim Neat.

The author’s characterisation of the work as a ‘long narrative poem’ is maybe a little misleading. What we’re given, in fact, is a montage of prose-poems, letters, photographs, newspaper articles and notes, which trace the story of Jim Neat’s early life, in particular his closeness to his sister, Queenie, his escape from family tensions as a stowaway to Cape Town, his subsequent journeying via Australia to Canada, his relationships and recovery from mental illness there, and his second marriage following his return to England. There are documents, too, detailing his war service in Algeria and Sicily, and several poems that explore Mary Oliver’s struggle to come to terms with his absence.

The book begins in Canada, where Jim Neat’s heart belongs. He’s ‘down on his luck’ – as the subtitle suggests – and presently an inmate of Toronto jail where he’s detained on a narcotics charge. Within two pages, though, we’re following the route that brought him to this pass, via his doctor’s case-notes and Jim’s poems, written in the Ontario hospital to which he was admitted in 1935 for psychiatric care. Like many a contemporary migrant, Jim has taken risks in his search for work, ‘riding the rods’ on freight trains, and he’s short of clothing to keep out the bitter minus temperatures.

‘We sit poking small fires, sharing stews and narcotics to numb the pain. I must escape this brotherhood of ailing flesh. But I need a coat. I root through a bundle of clothes in a trailer. It’s solid…a man, already dead. I undress him.’The crossing-out is a device used frequently in Jim’s therapeutic writing. It works well to suggest a mind still processing experience and at the edges of self-loathing. From his childhood, Jim has been a fan of Joseph Conrad, the inspiration of his early voyaging, and for this he blames his elementary school teacher Miss Thomas. De profundis, he cries out against her well-meant ignition of his imagination, and against the privations it has brought him to:

At the centre of the story is the crisis that has tipped him over into what might be a severe form of depression. Its origins lie in Jim’s romantic tragedy, the loss of his soul-mate Lizbietta and their child, Mary Oliver’s Canadian half-sister, Mariya. This part of the tale is largely supplied by another ‘found’ document, Lizbietta’s diary which covers the period between April 1932, when they met in the Saskatoon bookshop where she worked, and June 1935. The diary chronicles Jim’s settlement into the Ukrainian community, and the brief period of happiness and stability he found there. The entry for ‘Sunday 25th May 1932’ is the fulcrum on which this section pivots.

‘Supper finished, dishes washed and put away, we walked down to the river, watched the chipmunks for ages, taking the dry grass down into their little burrows. Scrambled down the steep bank to the sandy beach below. Afterwards we came back to my room. ‘Best day of my life,’ he said. Same was true for me. Jesus.’It’s a tough existence, mitigated by love and the support of their friend, Adam, a black porter on the Saskatoon Railroad, and Valentyna and Viktor, Lizbietta’s adoptive parents. Jim is forced to seek work away from home, and it’s on his return from one of these trips that the tragedy strikes. Lizbietta, he discovers, has died in childbirth and his daughter has been taken into the local orphanage. In his grief, he rushes wildly to the Home for Unmarried Girls and Illegitimate Babies and is arrested and committed to a hospital for the insane.

His recovery is largely due to the kind ministrations of Donald Fletcher, the Superintendent of the Whitby Hospital in Ontario where the young Jim finally washes up. Dr Fletcher’s enlightened regime and the gentle company of another inmate, the veterinary scientist Frank Schofield, prove sufficient to bring Jim back to life – a new life in England, with his sisters and eventually with the author’s mother, Kate.

The closing sections are formed principally from ‘Mary J. Oliver’s Note Book’ and ‘Mary J. Oliver’s Canada Diary’. The latter is sometimes a bit on the gushy side:

The former contains some of the most telling poems and prose-poems of the collection, which deal with her ambiguous feelings about her dad:

Among the ‘Found Documents’ there’s an ‘Exchange between my father and me’ from September 1982. In his letter to Mary, Jim explains how he chose her name – after her half- sister, Lizbietta’s lost daughter.

He goes on to tell her how proud he is of her forthcoming exhibition in Glasgow and encloses some drawings of his own. ‘What do you think? Any talent to speak of?’

The reply is five lines long, thanking him for, and praising, the drawings, and advising him to avoid darkening the pencil sketches with charcoal. The outstretched hand isn’t taken. Perhaps in this tribute, published thirty-eight years later, Mary J. Oliver has found her way of forgiving.

It’s an absorbing and thought-provoking book, and one which contains far more than there’s space to summarise here. I’m left, though, with a reservation, and it’s one that Oliver herself may have anticipated in her ‘Verdict’, the last item in the collection. This is simply a quotation from Vladimir Nabokov’s The Real Life of Sebastian Knight: ‘Remember that what you are told is really threefold: shaped by the teller, reshaped by the listener, concealed from both by the dead man of the tale.’ Oliver has declared, in both her You-tube interview and in the ‘Author’s Note’ that ‘where I found gaps in his narrative I have often augmented tantalising fragments of information with imagined details…and merged some events’ and that ‘there are a few invented figures who help move the story forward.’

As with that hybrid creature the ‘docu-drama’ you’re never quite sure where the factual documentation ends and the fiction begins. That’s not to argue that a poet can’t discover truths too deep for taint through empathy, through being there in soul and spirit, but the grey hinterland can be difficult territory. I have my doubts, for instance, about the ‘Document Enclosed in Queenie’s Letter / Bliss in Cape Town, 1921’ which purports to be a letter from a sweet fourteen year old ‘sex worker’ whom Jim encountered when he stowed away at the age of fifteen. No doubt someone will contact me to explain that, no, it’s word-for-word authentic; that’s always the way. Nevertheless, once sown, the uncertainty is there. It’s an unease that emerged again, for me, at one of the key moments in the narrative. The circumstances of Lizbietta’s death are finally revealed to Mary in a letter from Serge, Valentyna & Viktor’s son, dated 5th February 2008. The shock of the discovery of her body has caused him to become mute—for the rest of his life. His written account leaves a vivid impression, but he dates the event as happening in the drought of June 1936. According to Jim’s evidence, Lizbietta’s death occurred in ’35 and Jim was already in the Whitby Hospital by then. Old men, of course, can easily make slips with dates, even if they claim their memory is ‘excellent’. The incident is so heart-rending you wouldn’t want to make it up. The reader’s already on-side with Jim Neat. His story is compelling enough without dramatic embellishment.