In Translation: an exhibition of poetry by Katherine Venn

at the Westbourne Grove Church ArtSpace

at the Westbourne Grove Church ArtSpace

Westbourne Grove, London W11 2RW

January 9th – February 2nd

Normal opening times:

9 am to 5 pm on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday & Friday.

To visit at other times please call the church (020 7034 0500)

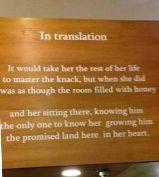

The very attractive art space within Westbourne Grove Church usually hosts exhibitions of paintings or sculptures. But for the next three weeks or so it will be hosting a display of poems by Katherine Venn. And the word “display” is appropriate because two of the poems appear to have been engraved on the gallery windows at street level, making a strong and immediate impression on  any visitor who arrives at dusk when the interior lights are on. Once inside the building, the visitor’s eye is caught by the exhibition’s title poem in bold white lettering on the wooden fascia of the church’s mezzanine floor.

any visitor who arrives at dusk when the interior lights are on. Once inside the building, the visitor’s eye is caught by the exhibition’s title poem in bold white lettering on the wooden fascia of the church’s mezzanine floor.

The remaining twenty or so poems are presented in less dramatic fashion, being printed (in a very readable typeface) on white board and hung, picture-fashion, on the walls. They are not confined to the main gallery space but are also placed on the walls of two offshoot corridors and in the hexagonal turret rooms at the ends of those corridors. So a visitor can go on a small literary treasure hunt, following clues left by the poet’s imagination.

Each poem is given enough space to allow the viewer to pay it sufficient attention. However it may take a little time to get used to reading text from a standing position; and the poems which made the biggest impression on me were those offering an immediate startling image. One of these is “Sweet Peas” which begins

I woke to find God sitting on my bed. ‘This

‘is going to hurt,’ she said, and reached into my chest

and pulled my heart up from its roots.

Two big surprises here: God not only appears in a suburban bedroom but does so wearing an unconventional gender! A search for some Biblical precedent for what seems to be a piece of Divine brutality might yield the prophet Ezekiel who speaks of God taking hearts of stone and replacing them with hearts of flesh. But here it is a heart of flesh that is removed! And what is given in exchange?

[she] took a fold of seeds out from her pocket,

shook out one, two, three into a palm

and dropped them in the space my heart had been. ‘Sweet

peas,’ she said, her fingers at my breast, and left.

Venn is, one soon discovers, much concerned with the human heart and its tenderness and susceptibility to being broken. She suspects however that animals might have something to teach us. “Letter from a dog to a broken heart” finds a canine analogy for the experience of loving and losing:

Poor heart that ran unthinking

for what was thrown for you

...

you lost yourself and him long gone.

Don’t be ashamed. It happens to dogs

too.

The loyal, optimistic doggie voice goes on to offer homely advice about consoling activities such as ‘Chase squirrels. You won’t catch them / but it’s not as though they mind.’

Cats on the other hand are probably too self-absorbed to offer advice to human beings. But “The lost cat” draws a perceptive parallel from a story about a cat being rescued from a curiosity-driven misadventure involving a locked garage and a bottle of linseed oil. Venn conjectures that we too are often ‘trapped / in the places where our instincts take us’ and suggests that we are unaware of all the influences that

... work our freedom with whatever is to hand,

jimmying the locks of our wrong turns

People sometimes have to learn from people too and “In reverse” encourages us to take both a direct and an indirect look at ourselves. Our situation seen in a mirror seems

suddenly so beguiling you wonder if life would lighten

if you could step into that other room,

where objects seem more true.

The only non-verbal piece in the exhibition is the image alongside the ekphrastic poem “Rembrandt’s ‘The Jewish Bride’” This poem is written in the bride’s voice and intriguingly mixes her real and painted identities as she speaks of ‘examining the tiny brush-strokes / of each other – the minute creases round / your eyes, a curl of hair that frames my face.’ She goes on to describe the couple’s intimacy in a way that carries a faint echo of that last quoted line from “Sweet Peas”

The only non-verbal piece in the exhibition is the image alongside the ekphrastic poem “Rembrandt’s ‘The Jewish Bride’” This poem is written in the bride’s voice and intriguingly mixes her real and painted identities as she speaks of ‘examining the tiny brush-strokes / of each other – the minute creases round / your eyes, a curl of hair that frames my face.’ She goes on to describe the couple’s intimacy in a way that carries a faint echo of that last quoted line from “Sweet Peas”

... contained within this

one square inch of canvas: my hand placed on yours,

yours on the red, the beating of my heart.

These few extracts demonstrate Venn’s lively and original poetic imagination which is well-served by her keen ear for the apt word or phrase. Her poems are unpretentiously well-crafted: “In reverse” makes accomplished use of terza rima; and the transition between paint and flesh in the Jewish Bride poem comes just at the turn of an unrhymed sonnet. Venn can also write in a more meditative mode than has been shown in the mainly narrative examples given so far; and visitors should look out for the remarkable sequence on seven “orders of rest” which deserves to be worked through carefully (and also walked through since the poems are not all grouped together) and does not lend itself to short easy quotes.

Katherine Venn has been writing poetry since the early 2000s and believes it is ‘one of the best ways of paying attention to the world.’ During the last year she has been working one day a week as a resident poet at the Westbourne Artcentre. Her regular job is in publishing with John Murray/Hodder & Stoughton and she has worked for a number of years in coordinating the literature programme of the Greenbelt Festival. Venn’s poetry has been widely published in magazines including Popshot and London Grip and she is one of the featured authors in the anthology Lyrical ( Rob Pepper, 2014). The exhibition In Translation should bring her poetry to the attention of the even wider audience it deserves.

Jan 11 2020

In Translation – Katherine Venn

In Translation: an exhibition of poetry by Katherine Venn

The very attractive art space within Westbourne Grove Church usually hosts exhibitions of paintings or sculptures. But for the next three weeks or so it will be hosting a display of poems by Katherine Venn. And the word “display” is appropriate because two of the poems appear to have been engraved on the gallery windows at street level, making a strong and immediate impression on any visitor who arrives at dusk when the interior lights are on. Once inside the building, the visitor’s eye is caught by the exhibition’s title poem in bold white lettering on the wooden fascia of the church’s mezzanine floor.

any visitor who arrives at dusk when the interior lights are on. Once inside the building, the visitor’s eye is caught by the exhibition’s title poem in bold white lettering on the wooden fascia of the church’s mezzanine floor.

The remaining twenty or so poems are presented in less dramatic fashion, being printed (in a very readable typeface) on white board and hung, picture-fashion, on the walls. They are not confined to the main gallery space but are also placed on the walls of two offshoot corridors and in the hexagonal turret rooms at the ends of those corridors. So a visitor can go on a small literary treasure hunt, following clues left by the poet’s imagination.

Each poem is given enough space to allow the viewer to pay it sufficient attention. However it may take a little time to get used to reading text from a standing position; and the poems which made the biggest impression on me were those offering an immediate startling image. One of these is “Sweet Peas” which begins

Two big surprises here: God not only appears in a suburban bedroom but does so wearing an unconventional gender! A search for some Biblical precedent for what seems to be a piece of Divine brutality might yield the prophet Ezekiel who speaks of God taking hearts of stone and replacing them with hearts of flesh. But here it is a heart of flesh that is removed! And what is given in exchange?

[she] took a fold of seeds out from her pocket, shook out one, two, three into a palm and dropped them in the space my heart had been. ‘Sweet peas,’ she said, her fingers at my breast, and left.Venn is, one soon discovers, much concerned with the human heart and its tenderness and susceptibility to being broken. She suspects however that animals might have something to teach us. “Letter from a dog to a broken heart” finds a canine analogy for the experience of loving and losing:

The loyal, optimistic doggie voice goes on to offer homely advice about consoling activities such as ‘Chase squirrels. You won’t catch them / but it’s not as though they mind.’

Cats on the other hand are probably too self-absorbed to offer advice to human beings. But “The lost cat” draws a perceptive parallel from a story about a cat being rescued from a curiosity-driven misadventure involving a locked garage and a bottle of linseed oil. Venn conjectures that we too are often ‘trapped / in the places where our instincts take us’ and suggests that we are unaware of all the influences that

People sometimes have to learn from people too and “In reverse” encourages us to take both a direct and an indirect look at ourselves. Our situation seen in a mirror seems

These few extracts demonstrate Venn’s lively and original poetic imagination which is well-served by her keen ear for the apt word or phrase. Her poems are unpretentiously well-crafted: “In reverse” makes accomplished use of terza rima; and the transition between paint and flesh in the Jewish Bride poem comes just at the turn of an unrhymed sonnet. Venn can also write in a more meditative mode than has been shown in the mainly narrative examples given so far; and visitors should look out for the remarkable sequence on seven “orders of rest” which deserves to be worked through carefully (and also walked through since the poems are not all grouped together) and does not lend itself to short easy quotes.

Katherine Venn has been writing poetry since the early 2000s and believes it is ‘one of the best ways of paying attention to the world.’ During the last year she has been working one day a week as a resident poet at the Westbourne Artcentre. Her regular job is in publishing with John Murray/Hodder & Stoughton and she has worked for a number of years in coordinating the literature programme of the Greenbelt Festival. Venn’s poetry has been widely published in magazines including Popshot and London Grip and she is one of the featured authors in the anthology Lyrical ( Rob Pepper, 2014). The exhibition In Translation should bring her poetry to the attention of the even wider audience it deserves.