Wendy Klein enjoys Keith Hutson’s artful recapturing of the atmosphere of Music Hall

Baldwin’s Catholic Geese

Keith Hutson

Bloodaxe Books

ISBN: 978 1 78037 455 0

128 pp £12

Baldwin’s Catholic Geese

Keith Hutson

Bloodaxe Books

ISBN: 978 1 78037 455 0

128 pp £12

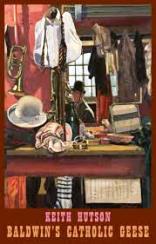

Baldwin’s Catholic Geese is a substantial book: 118 pages of poems and 10 pages of notes which reference each poem. Nonetheless, what reader would not be seduced by the enchanting title? Add to this the marvellous cover, ‘Comedian’s Corner’ (1932), painted by Harry Rutherford with its colourful array of costumes and contraptions. a device which looks like shackles, a white derby hat, and a large brass horn without a mouthpiece, not to mention a rosy comedian smiling in the background.

I am coming late as a reviewer to this collection – which was published early in 2019 – and I am already preceded by a list of ecstatic readers with pedigrees more imposing than my own. Andy Croft, of ‘Morning Star’ describes it as ‘a hugely entertaining celebration of British music hall and variety artists.’ Carol Rumens in ‘Our Daily Read’ notes ‘this collection delivers the comedy and oddity its title promises, but it amounts to very much more than a novelty act.’ The most comprehensive and fulsome praise I have read comes from Steve Whitaker, literary correspondent of the Yorkshire Times. Whitaker gives a generous nod to Keith’s professional background as a television scriptwriter and poet ‘moulded through the refracting glass of youthful memories,’ commenting that ‘the man who grew out of early obsession and the world of television is well placed to make meaningful judgement on all our behalves.’ He concludes that, ‘There’s more than artistry to Hutson’s peerless volume.’

First off, the sonnet is Keith Hutson’s playground. I set myself the task of counting the number of sonnets in this book as compared to poems of other forms/lengths and tired of the exercise before I’d finished. It’s safe to say, that most of the poems in the book are 14 brilliant lines long. As it happens, the opening poem is not, though the sense of mastery emerges as the poet offers advice to someone, probably a theatre manager about who to hire to open the show:

See every house, before it settles,

as a beast not fully backed into its cage.

As someone who has trodden the boards, looked out on that ‘house’, every word rings true. But let the sonnets begin, each one a short biography of a music hall performer. Joan Rhodes (1921- 2010), who

bent iron bars, broke nails, took four men

on at tug-of-war and won, which led to

lifting Bob Hope while Marlene Dietrich

loved a woman tough enough to keep

refusing King Farouk, who wanted you

to wreck his four-poster bed with him

still in it. ( … )

(“Coming on Strong”, p.11)

Apart from the genius of the image, what a volte! But turn and turn again, in a list of performers where freaks of nature find stardom on the music hall circuit, in “Immense” (i.m. Little Tich 1867-1928), Hutson scores again. Beginning with six lines of pathos, he finishes with:

… Make him Victorian – reason

enough to stop at four feet six and doubt

the prospect of old bones. How long would be

the odds on one so lost learning to dance;

Addressing one of his subjects in the context of a perennially relevant issue, self-starvation, the poet compares Giovanni Succi 1853-1905 to Frances Thomas 1935-1978, probably the poet’s own aunt:

His photograph, all fade and gaze, still

holds the absent presence of an aunt of mine,

less lionised, who starved herself to death –

but she was no phenomenon, ‘just vain’.

(“The Art of Hunger”, p. 44)

Hutson’s glitter-ball stage is tawdry and tarnished, but still gleaming, as over and over he blends humour, irony and pathos, managing to be poignant and sassy at once. The school bully, becomes an act as ‘Town Crier’ who

… in the Civic Centre, wrings the neck

of a bell, licensed at last to cause alarm,

make children cling to mums who stoop and flinch.

(“Town Crier”, p. 95)

And what of Old Mother Riley? I love the way he turns the humour of humiliation, always uncomfortable to watch, into tragic irony:

Old Mother Riley, Arthur Lucan

in a bonnet, married a woman

half his age who turned into his daughter

every evening on the stage,

but when curtains were closed,

she called on better men than him

to strip away the minor role

she played.

(“Family Business, I”., p.24)

For me the revelation of Charles Aznavour is perhaps the most heart-breaking with its opening question to the reader:

Fed up with feeling optimistic?

Put Charles on, whose height or lack of it,

was one of the few things he laughed about.

That, and being named, time and again,

the World’s Best-Known Armenian.

‘Edith Piaf’, the poet reveals, lent President de Gaulle her handkerchief’ as they listened together to the song in celebration of the European Union. Given what is happening today to the European Union, perhaps it should be played on every radio station, but the closing tercets of this poem sent me to my handkerchief with its ring of truth and humanity:

I’m paid per sob, he told

Le Figaro. Perhaps his own could

be traced back to twenty, when he sheltered

Jewish families, their lives and his at risk.

Listen to She, hear how bleak happiness

can be: there’s more than artistry to this.

(“Chanteur, i.m. Charles Aznavour 1924-2018” pp 114-115)

This one is not a sonnet.

I cannot recommend this book too highly. If you have not lived long enough to have experienced vaudeville/music hall theatre, or to have heard your grandparents rave about it, you can read it all here. The artistry of Keith Hutson. nuanced, never forced, brings it back to life again. Be sure to look sharp though; beguiled by the characters, you may lose sight of the craft, the genius blend of pathos and humour threaded through every poem. Read it.

Sep 12 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Keith Hutson

Wendy Klein enjoys Keith Hutson’s artful recapturing of the atmosphere of Music Hall

Baldwin’s Catholic Geese is a substantial book: 118 pages of poems and 10 pages of notes which reference each poem. Nonetheless, what reader would not be seduced by the enchanting title? Add to this the marvellous cover, ‘Comedian’s Corner’ (1932), painted by Harry Rutherford with its colourful array of costumes and contraptions. a device which looks like shackles, a white derby hat, and a large brass horn without a mouthpiece, not to mention a rosy comedian smiling in the background.

I am coming late as a reviewer to this collection – which was published early in 2019 – and I am already preceded by a list of ecstatic readers with pedigrees more imposing than my own. Andy Croft, of ‘Morning Star’ describes it as ‘a hugely entertaining celebration of British music hall and variety artists.’ Carol Rumens in ‘Our Daily Read’ notes ‘this collection delivers the comedy and oddity its title promises, but it amounts to very much more than a novelty act.’ The most comprehensive and fulsome praise I have read comes from Steve Whitaker, literary correspondent of the Yorkshire Times. Whitaker gives a generous nod to Keith’s professional background as a television scriptwriter and poet ‘moulded through the refracting glass of youthful memories,’ commenting that ‘the man who grew out of early obsession and the world of television is well placed to make meaningful judgement on all our behalves.’ He concludes that, ‘There’s more than artistry to Hutson’s peerless volume.’

First off, the sonnet is Keith Hutson’s playground. I set myself the task of counting the number of sonnets in this book as compared to poems of other forms/lengths and tired of the exercise before I’d finished. It’s safe to say, that most of the poems in the book are 14 brilliant lines long. As it happens, the opening poem is not, though the sense of mastery emerges as the poet offers advice to someone, probably a theatre manager about who to hire to open the show:

As someone who has trodden the boards, looked out on that ‘house’, every word rings true. But let the sonnets begin, each one a short biography of a music hall performer. Joan Rhodes (1921- 2010), who

bent iron bars, broke nails, took four men on at tug-of-war and won, which led to lifting Bob Hope while Marlene Dietrich loved a woman tough enough to keep refusing King Farouk, who wanted you to wreck his four-poster bed with him still in it. ( … ) (“Coming on Strong”, p.11)Apart from the genius of the image, what a volte! But turn and turn again, in a list of performers where freaks of nature find stardom on the music hall circuit, in “Immense” (i.m. Little Tich 1867-1928), Hutson scores again. Beginning with six lines of pathos, he finishes with:

Addressing one of his subjects in the context of a perennially relevant issue, self-starvation, the poet compares Giovanni Succi 1853-1905 to Frances Thomas 1935-1978, probably the poet’s own aunt:

His photograph, all fade and gaze, still holds the absent presence of an aunt of mine, less lionised, who starved herself to death – but she was no phenomenon, ‘just vain’. (“The Art of Hunger”, p. 44)Hutson’s glitter-ball stage is tawdry and tarnished, but still gleaming, as over and over he blends humour, irony and pathos, managing to be poignant and sassy at once. The school bully, becomes an act as ‘Town Crier’ who

… in the Civic Centre, wrings the neck of a bell, licensed at last to cause alarm, make children cling to mums who stoop and flinch. (“Town Crier”, p. 95)And what of Old Mother Riley? I love the way he turns the humour of humiliation, always uncomfortable to watch, into tragic irony:

Old Mother Riley, Arthur Lucan in a bonnet, married a woman half his age who turned into his daughter every evening on the stage, but when curtains were closed, she called on better men than him to strip away the minor role she played. (“Family Business, I”., p.24)For me the revelation of Charles Aznavour is perhaps the most heart-breaking with its opening question to the reader:

‘Edith Piaf’, the poet reveals, lent President de Gaulle her handkerchief’ as they listened together to the song in celebration of the European Union. Given what is happening today to the European Union, perhaps it should be played on every radio station, but the closing tercets of this poem sent me to my handkerchief with its ring of truth and humanity:

be traced back to twenty, when he sheltered Jewish families, their lives and his at risk. Listen to She, hear how bleak happiness can be: there’s more than artistry to this. (“Chanteur, i.m. Charles Aznavour 1924-2018” pp 114-115)This one is not a sonnet.

I cannot recommend this book too highly. If you have not lived long enough to have experienced vaudeville/music hall theatre, or to have heard your grandparents rave about it, you can read it all here. The artistry of Keith Hutson. nuanced, never forced, brings it back to life again. Be sure to look sharp though; beguiled by the characters, you may lose sight of the craft, the genius blend of pathos and humour threaded through every poem. Read it.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, comedy, poetry reviews 0 • Tags: books, poetry, Wendy Klein