Carla Scarano looks at poems by Valerie Lynch that explore relationships and experiences across the whole of life

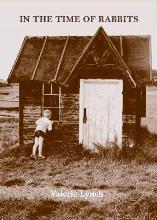

In the Time of Rabbits

Valerie Lynch

Dempsey & Windle 2019

ISBN 9781907435782

£ 11.00

In the Time of Rabbits

Valerie Lynch

Dempsey & Windle 2019

ISBN 9781907435782

£ 11.00

New themes and expanding images and metaphors are explored in Valerie Lynch’s second collection, In the Time of Rabbits. A wider conception of family relationships and identity is developed in recollections from her childhood and adulthood. The narrative concerns a woman’s lineage that goes from her grandmother back in the 1920s to her mother’s girlhood, marriage and relationship with her husband. The crystallised roles of wife and mother are contested in the narrator’s own story which includes break-ups and new lovers. Other themes are investigated such as aging, illness, gender issues, immigrants. The collection includes ekphrastic poetry and ends with a question suggesting that what we have just read is provisional though the aesthetic pleasure the poems prompt is undeniable.

The collection opens with a dedicatory poem to the poet’s son who helps young men to ‘give names to their fears/the fears of childhood//and clothe them for today’. In a similar way, Lynch’s poems voice those fears and ‘clothe them’ for today as well as for a past which is viewed through the lens of experience in a new open vision that resists closure and engenders unexpected imageries.

Lynch’s narrator can shape herself like sand, make herself ‘something different’ (“The Shape and me’), explore her life from a different angle. In her childhood ‘all things were possible/and waiting to be lived’ (‘In the Time of Rabbits’). The mother figure appears in several poems, as a young woman ‘so young, so vivid,/so unaware of her nineteen years/of innocence’ (‘Barefoot’); but she is also seen as formal and slightly frightened in ‘her wedding dress and wedding smile’ (‘Reading a photograph’). She is a shifting figure entrapped in her role of wife and mother revealing severity and self-denial:

The kettle sang carefully

around her head. The flowers and I,

dad and the kettle’s song

were anxious to please.

Perhaps

we brought her some rest

from the artillery

that garrisoned her smiles.

(‘The Strawberry Fields’)

She suffers ‘Absences’ and silences and misses a real connection with her daughter:

I told you HALF a pound, she said,

with us standing there in the road.

And this time, get the proper change!

…

Trying not to breathe, I chopped him up,

minced the bits, and stuffed them

in sausage skins. Put mum in too,

then took her out quick. She often

sees my thinks.

(‘Sausages’)

The poems about the mother suggest repressed potential, an ‘otherwise’ that was silenced by education, social conventions and marriage. Nevertheless, the young narrator has a special connection with her grandmother, Granny T, who enlightens her about ancestors, their ‘feasting and song’. She lived in a ‘two up two down/cold scullery’ called ‘sookies’, ‘in the briskness of Dorset hills’ where there are no ‘published regulations’. If the mother expects perfection and obedience to social rules, the grandmother is looser and always welcoming, she leaves her be:

I cycled over to see you each day after school to sit

and not say a word, and have you not to say a word to me,

just leaving me be.

(‘The button box’)

The mother comes back in her adulthood. The poet watches ‘her face slide’ beneath her skin (‘Becoming and vanishing’); it is a legacy the poet acknowledges and dismisses at the same time in an attempt to achieve an identity which is necessarily different from her mother’s.

The relationship with her father is connected with bedtime stories from the war, as in the poem ‘German Boy’. During the first world war the father spared the life of a German soldier who stared at his bayonet holding out his hands. According to the rules, the father should have struck with the bayonet and twisted it in the boy’s body; but he did not and let him go.

Some poems show the sufferings and illusions of a broken relationship that are counterbalanced by a new love flourishing in later life:

You said you don’t do belonging;

you didn’t pretend.

I didn’t hear your words.

I loved the smell of your skin.

I loved.

(‘Herb Robert’)

The new love is not binding or stable, it is provisional but it seems to meet the poet’s desire and expectations. He fills unpredictable needs that her parents never fulfilled due to their stiff prescribed roles. The poet’s new lover was ‘always ready to leave’ and finally managed it when he suddenly died. However, not only is love temporary, but everything that concerns life and our humanity is necessarily provisional. This is because of our mortality as well as the sense of openness and playfulness that Lynch’s poetry suggests:

Morning holds the long slow sky

of winter, stretched thin over Chesil’s Reach.

Between shingle and sky, nothing moves.

Softly, a sea-mist slides across the shore,

its shroud holding me fast.

(‘Chesil’s Reach’)

The old sun arcs low

days briefly stutter

and shiver

A voice sings on the river

a herring gull screams

and dies.

Tomorrow

daybreak

will open early.

Streets rouse the sky

a boy flings by

on a bike.

(‘Equinox’)

In ‘Chesil’s Reach’ death is evoked in the word ‘shroud’ foreseen in the alliterations with ‘shingle’, ‘sky’ and ‘shore’. Contingency and mystery haunt the poem, while in ‘Equinox’ a lighthearted mood is present in the meditative pauses of the line breaks and especially in the half rhyme of the conclusion. The final image of the boy riding a bike points towards the future and the rest of life. The ordinary is therefore connected with the universal where ancient myths merge with everyday life, as in the poem ‘Promises’, and with a surreal world that has a touch of humour:

I see the mackerel march off

their slab in militant array.

…

‘It’s still alive.’ You stupid woman.

He grins. Dead long before you

got up today, I reckon.

I am watching mackerel eyes

as they meet mine.

You want it, or not?

(‘Mackerel eyes’)

Lynch reflects on words, images and how they construct reality. In her poem ‘Looking is different from seeing’ The cow she sees in the field is ‘a sort of bundle/of brown and white’ that does not resemble the cow of her picture book: ‘That isn’t a cow. I know cow’. Once again reality reveals itself as uncertain, sometimes disappointing and always conveying blurred images hard to catch or define:

I spin down my net

to catch the words

that fall in the black sleeps of night

before the sun drops in

and strangles them.

(‘Word-hunter 2’)

This thought is further explored in the poems that describe pictures. Lynch ‘feels’ the painting rather than simply describing it; it is a synesthetic approach that makes the reader experience the artwork with all the senses:

The wind is tossing sulky Thames water

across the road and into my hair,

freezing my neck, filling my eyes with tears.

Turner has wrenched me inside out.

His ‘Storm’ has lashed sea in my face

I’m wet as a cabin-boy on his drowning ship.

(‘Water, drowned in light’)

This new collection is not only rich in imageries, it also reveals a widening of Lynch’s poetic and literary horizons both in her prosody and in her perceptions. Considering her age (she is ninety-two), Valerie Lynch is the living proof of the never ending potentials of imagination that create alternative views, new beginnings and new possibilities.

Aug 29 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Valerie Lynch

Carla Scarano looks at poems by Valerie Lynch that explore relationships and experiences across the whole of life

New themes and expanding images and metaphors are explored in Valerie Lynch’s second collection, In the Time of Rabbits. A wider conception of family relationships and identity is developed in recollections from her childhood and adulthood. The narrative concerns a woman’s lineage that goes from her grandmother back in the 1920s to her mother’s girlhood, marriage and relationship with her husband. The crystallised roles of wife and mother are contested in the narrator’s own story which includes break-ups and new lovers. Other themes are investigated such as aging, illness, gender issues, immigrants. The collection includes ekphrastic poetry and ends with a question suggesting that what we have just read is provisional though the aesthetic pleasure the poems prompt is undeniable.

The collection opens with a dedicatory poem to the poet’s son who helps young men to ‘give names to their fears/the fears of childhood//and clothe them for today’. In a similar way, Lynch’s poems voice those fears and ‘clothe them’ for today as well as for a past which is viewed through the lens of experience in a new open vision that resists closure and engenders unexpected imageries.

Lynch’s narrator can shape herself like sand, make herself ‘something different’ (“The Shape and me’), explore her life from a different angle. In her childhood ‘all things were possible/and waiting to be lived’ (‘In the Time of Rabbits’). The mother figure appears in several poems, as a young woman ‘so young, so vivid,/so unaware of her nineteen years/of innocence’ (‘Barefoot’); but she is also seen as formal and slightly frightened in ‘her wedding dress and wedding smile’ (‘Reading a photograph’). She is a shifting figure entrapped in her role of wife and mother revealing severity and self-denial:

The kettle sang carefully around her head. The flowers and I, dad and the kettle’s song were anxious to please. Perhaps we brought her some rest from the artillery that garrisoned her smiles. (‘The Strawberry Fields’)She suffers ‘Absences’ and silences and misses a real connection with her daughter:

I told you HALF a pound, she said, with us standing there in the road. And this time, get the proper change! … Trying not to breathe, I chopped him up, minced the bits, and stuffed them in sausage skins. Put mum in too, then took her out quick. She often sees my thinks. (‘Sausages’)The poems about the mother suggest repressed potential, an ‘otherwise’ that was silenced by education, social conventions and marriage. Nevertheless, the young narrator has a special connection with her grandmother, Granny T, who enlightens her about ancestors, their ‘feasting and song’. She lived in a ‘two up two down/cold scullery’ called ‘sookies’, ‘in the briskness of Dorset hills’ where there are no ‘published regulations’. If the mother expects perfection and obedience to social rules, the grandmother is looser and always welcoming, she leaves her be:

I cycled over to see you each day after school to sit and not say a word, and have you not to say a word to me, just leaving me be. (‘The button box’)The mother comes back in her adulthood. The poet watches ‘her face slide’ beneath her skin (‘Becoming and vanishing’); it is a legacy the poet acknowledges and dismisses at the same time in an attempt to achieve an identity which is necessarily different from her mother’s.

The relationship with her father is connected with bedtime stories from the war, as in the poem ‘German Boy’. During the first world war the father spared the life of a German soldier who stared at his bayonet holding out his hands. According to the rules, the father should have struck with the bayonet and twisted it in the boy’s body; but he did not and let him go.

Some poems show the sufferings and illusions of a broken relationship that are counterbalanced by a new love flourishing in later life:

You said you don’t do belonging; you didn’t pretend. I didn’t hear your words. I loved the smell of your skin. I loved. (‘Herb Robert’)The new love is not binding or stable, it is provisional but it seems to meet the poet’s desire and expectations. He fills unpredictable needs that her parents never fulfilled due to their stiff prescribed roles. The poet’s new lover was ‘always ready to leave’ and finally managed it when he suddenly died. However, not only is love temporary, but everything that concerns life and our humanity is necessarily provisional. This is because of our mortality as well as the sense of openness and playfulness that Lynch’s poetry suggests:

Morning holds the long slow sky of winter, stretched thin over Chesil’s Reach. Between shingle and sky, nothing moves. Softly, a sea-mist slides across the shore, its shroud holding me fast. (‘Chesil’s Reach’) The old sun arcs low days briefly stutter and shiver A voice sings on the river a herring gull screams and dies. Tomorrow daybreak will open early. Streets rouse the sky a boy flings by on a bike. (‘Equinox’)In ‘Chesil’s Reach’ death is evoked in the word ‘shroud’ foreseen in the alliterations with ‘shingle’, ‘sky’ and ‘shore’. Contingency and mystery haunt the poem, while in ‘Equinox’ a lighthearted mood is present in the meditative pauses of the line breaks and especially in the half rhyme of the conclusion. The final image of the boy riding a bike points towards the future and the rest of life. The ordinary is therefore connected with the universal where ancient myths merge with everyday life, as in the poem ‘Promises’, and with a surreal world that has a touch of humour:

I see the mackerel march off their slab in militant array. … ‘It’s still alive.’ You stupid woman. He grins. Dead long before you got up today, I reckon. I am watching mackerel eyes as they meet mine. You want it, or not? (‘Mackerel eyes’)Lynch reflects on words, images and how they construct reality. In her poem ‘Looking is different from seeing’ The cow she sees in the field is ‘a sort of bundle/of brown and white’ that does not resemble the cow of her picture book: ‘That isn’t a cow. I know cow’. Once again reality reveals itself as uncertain, sometimes disappointing and always conveying blurred images hard to catch or define:

I spin down my net to catch the words that fall in the black sleeps of night before the sun drops in and strangles them. (‘Word-hunter 2’)This thought is further explored in the poems that describe pictures. Lynch ‘feels’ the painting rather than simply describing it; it is a synesthetic approach that makes the reader experience the artwork with all the senses:

The wind is tossing sulky Thames water across the road and into my hair, freezing my neck, filling my eyes with tears. Turner has wrenched me inside out. His ‘Storm’ has lashed sea in my face I’m wet as a cabin-boy on his drowning ship. (‘Water, drowned in light’)This new collection is not only rich in imageries, it also reveals a widening of Lynch’s poetic and literary horizons both in her prosody and in her perceptions. Considering her age (she is ninety-two), Valerie Lynch is the living proof of the never ending potentials of imagination that create alternative views, new beginnings and new possibilities.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2019 0 • Tags: books, Carla Scarano, poetry