Logos: Where Word and Flesh Interact: Brian Docherty takes a close look at Dinah Livingstone’s 10th collection

Embodiment

Dinah Livingstone

Katabasis, (10 St. Martins’s Close, London NW1 0HR)

ISBN 978 - 0 - 904872 -49-1

£10

Embodiment

Dinah Livingstone

Katabasis, (10 St. Martins’s Close, London NW1 0HR)

ISBN 978 - 0 - 904872 -49-1

£10

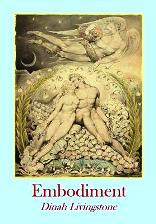

Dinah Livingstone’s 10th full collection announces its intentions and allegiances before we even open the book. The cover features one of William Blake’s illustrations to Milton’s Paradise Lost, ‘Satan envies the endearments of Adam and Eve’. Livingstone, as a writer and tutor, situates herself in a line of English radicalism that includes both Blake and Milton. As a creative writing tutor, she has mentored a great many poets, including your reviewer. Her other achievements include being the leading translator of the poets of the Nicaraguan Revolution. A note at the front of the book reminds us of her West Country heritage, but also that she has been rooted in a community in Camden Town since 1966.

The first of the book’s two sections, VOICES, leads with ‘The Poetic Planet’ which starts in Devon but moves out, seeing our planet from an external perspective, then moves in with a nods to David Attenborough

Homing in we see blue oceans,

shapes of continents appear,

soon forests, large green patches,

and brilliant blobs are cities.

Then what can be heard is conversation.

In stanza 4, people are ‘expressing how it feels to be an earthling’. A persistent feature of Livingstone’s work for many years has been the deeply held belief that what makes us human is fellowship, community, and conversation; and accordingly this poem concludes

One species among many that belong,

evolution’s product, moral like the rest,

fallible, linguistic, making the planet

articulate her story, form the poem

wording Earth’s deep hum.

The ecological, political, and spiritual beliefs expressed here stand as a rebuke to the destructive cynicism, vanity and bad faith of politicians.

‘Drowned Voices’ touches on the ongoing crisis whereby refugees paying money to criminal gangs are either drowning at sea, or being held in detention camps( if they survive) before often being returned to a ‘home’ they were obliged to leave. In many tongues these voices cry out

Help me.

I am a human being.

Fellow creatures, weep,

weep for me.

The poem concludes

Who Listens?

Something is very wrong.

What can we do?

‘Loved Voices’ is more immediately personal, while ‘January’ reminds us that Roman god Janus faces both ways and lends his name to a dark time of year when we ‘feel that ancient fear; / What if the light never comes back?’

‘The Yearning Strong’ is a science fiction poem in the persona of someone whose great grandparents left out planet, while ‘The Smell of Memory’ is set in Camden Town, but looks out, and looks back to Livingstone’s time in Paris in her ‘naive teens’, before a meditation on the Farsi word paridaiza, equating ‘garden’ and ‘heaven’ after which we move on to Hampstead Heath,

On Hampstead Heath a child

toddles past a lavender bush,

his mother picks a flowerhead and sniffs,

offers it to him saying ‘Mm! delicious!’

He sniffs ‘Mm! delicious!’ copying her

and every time they pass that way

wants to repeat the ritual once again.

This, for Livingstone, is how real education works, not in school or online, but in real time, mother to child, shared values passed on.

Two short poems, ‘A Communication Failure’ and ‘Telecommunication’ show the exact opposite – presumably a younger generation missing out on real, person to person communication. ‘Dumb Animal’ is a reflection on living with a cat as companion, who can communicate very effectively, and is anything but dumb. The theme of communication, whether between people, or people and animals is explored further in three sonnets, ‘Boy and Fox’, ‘Japanese Great Tits’ and ‘The Greek Teacher’, and then we reach a memorial poem for a near neighbour, ‘For Maureen’. Living in a community has its benefits, but there is also the inevitable loss, of saying goodbye to friends such as Maureen,

She know everyone and everyone

knows her. She is the spirit

of St. Martin’s Gardens. Green-fingered

herself, the red camellia by her front door

is the best in the street.

In the last stanza, we learn that Maureen was

A friend and good neighbour for decades,

she was a Londoner. When they were little

our children played out in the street.

In the fifth of November the bonfire was huge.

And her four children and their children

are still going strong and are all right.

Yes, Maureen, that’s what you were and are.

All right.

This is followed by a tribute to Stevie Smith, an exemplar and favourite poet of Livingstone’s. In ‘Stevie’s Voice’ , she remembers Smith’s way of reading, ‘slightly off key’; ‘glass that can cut like a laser’. Anyone not familiar with Stevie Smith’s poetry will, I hope, be pleasantly surprised by the quotes from Smith embedded in Livingstone’s poem.

Section Two of this book, ‘Embodiment’ includes the title poem as part of a sequence, but starts with ‘Alpha and Omega’, noting that

In Blake’s illustration to Paradise Lost

Adam and Eve are Alpha and Omega.

Naked they lie in their blissful bower

between two curling fronds

and Satan envies them.

We are then reminded that the Old Testament God, Yahweh, is a jealous god, and that human history begins with Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden. Livingstone goes on to show that her version of Christianity is a New Testament ministry of Love, where

He lives on in a new humanity

as firstborn, figurehead, Omega ideal

of freedom and abundant life for all;

the full embodiment of Christ will be

an actual embodiment of kindness long imagined,

which now – with nothing supernatural -

ordinary people try (or not)

by love and work to give something towards.

Livingstone is involved with the Sea of Faith movement, SOFIA, and edits the magazine Sofia; check it out for yourselves, even those of other faiths or none may find that interesting and valuable things are being said there.

‘Both’ is a rebuke to anyone who believes that religion and politics can ever be separated, and reminds us that the personal is indeed the political.

The goddess Astarte Ishtar Ashtoreth

was the great mother. Yahweh,

their male god,

ordered the children of Israel

to crush her utterly, smash all her shrines:

she was wrong, abominable,

and it was wrong to honour her.

When I was young

my mother went off with another man,

then died of lung cancer.

I was told she was in the wrong

and that I should not miss her

but I did.

I wanted both a mother and a father.

The intersection and interaction between human action, belief, and faith is further explored in poems where cold weather in the now brings back memories of a cold stepmother in the past, including a series of three untitled sonnets, ‘Keeping Faith’ . The first asks

So are you faithless if you be yourself,

believe in life on Earth and humankind?

Aren’t faith and hope and love a constant quest

to fumble through and struggle to fulfil,

embody an idea you have in mind?

while the second, ‘Two Women’ is a dialogue about the nature of the self, and whether we even have a ‘self’. In reply to whether knowing we have a self is ‘just selfishness’ the reply is

No, it’s your good luck, keeps you alive.

Self-seeking is the curse of selflessness

but you speak for yourself. At least, that’s more.

The third sonnet expresses at least part of Livingstone’s personal theology, a version of faith that has no use for supernatural beings, and asks

Can’t faith in the divine vision also thrive,

now grown into a more mature poetic tale,

becoming what was in it all the time?

There are also a range of more ‘domestic’ or ‘nature’ poems, including ‘Nature and Grace’ where we get a story about Livingstone’s first paid translation, and her then husband’s reaction on learning that she spent the money on a new washing machine

My husband was angry.

‘You should have consulted me.’

he said, ‘it’s our money.’

I replied ‘It’s our washing.’

He looked bewildered,

the idea had not occurred.

The Prologue to the six poems of the sequence asks

How could a disembodied spirit speak

or dance or sing the paradox, the power,

the passing and the truth of human hearts?

Voices, voicing, what it means to be human, and have an embodied voice, are at the heart of this book, and births, human or other, feature prominently. Livingstone’s children also feature, as well as poems set in her neighbourhood, where she says of a builder, in the poem ‘Work’

I don’t tell him I saw him heroic,

the personification of Work,

builder of cities, as is Love.

In ‘Love’, she quotes St. Augustine and William Morris

My love is my weight, Augustine said,

my gravity. We fall in love,

and it is personal.

She goes on to quote Morris’s John Ball’s words that ‘fellowship is life and lack of fellowship / is death.’ In stanza 4, she says

love is what we cannot do without,

love builds the city

through accumulation of encounters -

chats in the corner shop, friends,

kindred spirits and darlings of your heart -

creating a habitat, a home that is

a lit galaxy like the stars above

but with consciousness and feeling,

attraction that is wholly human.

This is the voice of lived experience, and a lifetime’s devotion to the craft of making poems, informed by a unity of political belief and theology. There are poems of acceptance of bodily ageing to follow, such as ‘Ageing’ and ‘Death and After’, and in ‘Sleep Sealed’, the joy of receiving an unexpected Christmas present. The book closes with ‘The Dance’, and its last words are

Let hope or heart not fail

and the dance go on.

Thank you Life.

Here is the voice of Sophia, female wisdom, speaking words of love, fellowship, and reminding us that as fellow creatures, we stand or fall together, but acting together in Love, we can indeed build that City.

One last thing; as regular readers will know, I am sometimes dismayed by poorly produced and badly typeset books from publishers who have apparently never troubled to read Hart’s Rules. I am pleased to say that Embodiment, like all Katabasis books, is a properly printed and handsome book with an attractive and distinctive look. This book deserves to make a window display in Waterstones Camden High St. shop.

Aug 14 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Dinah Livingstone

Logos: Where Word and Flesh Interact: Brian Docherty takes a close look at Dinah Livingstone’s 10th collection

Dinah Livingstone’s 10th full collection announces its intentions and allegiances before we even open the book. The cover features one of William Blake’s illustrations to Milton’s Paradise Lost, ‘Satan envies the endearments of Adam and Eve’. Livingstone, as a writer and tutor, situates herself in a line of English radicalism that includes both Blake and Milton. As a creative writing tutor, she has mentored a great many poets, including your reviewer. Her other achievements include being the leading translator of the poets of the Nicaraguan Revolution. A note at the front of the book reminds us of her West Country heritage, but also that she has been rooted in a community in Camden Town since 1966.

The first of the book’s two sections, VOICES, leads with ‘The Poetic Planet’ which starts in Devon but moves out, seeing our planet from an external perspective, then moves in with a nods to David Attenborough

Homing in we see blue oceans, shapes of continents appear, soon forests, large green patches, and brilliant blobs are cities. Then what can be heard is conversation.In stanza 4, people are ‘expressing how it feels to be an earthling’. A persistent feature of Livingstone’s work for many years has been the deeply held belief that what makes us human is fellowship, community, and conversation; and accordingly this poem concludes

One species among many that belong, evolution’s product, moral like the rest, fallible, linguistic, making the planet articulate her story, form the poem wording Earth’s deep hum.The ecological, political, and spiritual beliefs expressed here stand as a rebuke to the destructive cynicism, vanity and bad faith of politicians.

‘Drowned Voices’ touches on the ongoing crisis whereby refugees paying money to criminal gangs are either drowning at sea, or being held in detention camps( if they survive) before often being returned to a ‘home’ they were obliged to leave. In many tongues these voices cry out

Help me. I am a human being. Fellow creatures, weep, weep for me.The poem concludes

Who Listens? Something is very wrong. What can we do?‘Loved Voices’ is more immediately personal, while ‘January’ reminds us that Roman god Janus faces both ways and lends his name to a dark time of year when we ‘feel that ancient fear; / What if the light never comes back?’

‘The Yearning Strong’ is a science fiction poem in the persona of someone whose great grandparents left out planet, while ‘The Smell of Memory’ is set in Camden Town, but looks out, and looks back to Livingstone’s time in Paris in her ‘naive teens’, before a meditation on the Farsi word paridaiza, equating ‘garden’ and ‘heaven’ after which we move on to Hampstead Heath,

On Hampstead Heath a child toddles past a lavender bush, his mother picks a flowerhead and sniffs, offers it to him saying ‘Mm! delicious!’ He sniffs ‘Mm! delicious!’ copying her and every time they pass that way wants to repeat the ritual once again.This, for Livingstone, is how real education works, not in school or online, but in real time, mother to child, shared values passed on.

Two short poems, ‘A Communication Failure’ and ‘Telecommunication’ show the exact opposite – presumably a younger generation missing out on real, person to person communication. ‘Dumb Animal’ is a reflection on living with a cat as companion, who can communicate very effectively, and is anything but dumb. The theme of communication, whether between people, or people and animals is explored further in three sonnets, ‘Boy and Fox’, ‘Japanese Great Tits’ and ‘The Greek Teacher’, and then we reach a memorial poem for a near neighbour, ‘For Maureen’. Living in a community has its benefits, but there is also the inevitable loss, of saying goodbye to friends such as Maureen,

She know everyone and everyone knows her. She is the spirit of St. Martin’s Gardens. Green-fingered herself, the red camellia by her front door is the best in the street.In the last stanza, we learn that Maureen was

A friend and good neighbour for decades, she was a Londoner. When they were little our children played out in the street. In the fifth of November the bonfire was huge. And her four children and their children are still going strong and are all right. Yes, Maureen, that’s what you were and are. All right.This is followed by a tribute to Stevie Smith, an exemplar and favourite poet of Livingstone’s. In ‘Stevie’s Voice’ , she remembers Smith’s way of reading, ‘slightly off key’; ‘glass that can cut like a laser’. Anyone not familiar with Stevie Smith’s poetry will, I hope, be pleasantly surprised by the quotes from Smith embedded in Livingstone’s poem.

Section Two of this book, ‘Embodiment’ includes the title poem as part of a sequence, but starts with ‘Alpha and Omega’, noting that

In Blake’s illustration to Paradise Lost Adam and Eve are Alpha and Omega. Naked they lie in their blissful bower between two curling fronds and Satan envies them.We are then reminded that the Old Testament God, Yahweh, is a jealous god, and that human history begins with Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden. Livingstone goes on to show that her version of Christianity is a New Testament ministry of Love, where

He lives on in a new humanity as firstborn, figurehead, Omega ideal of freedom and abundant life for all; the full embodiment of Christ will be an actual embodiment of kindness long imagined, which now – with nothing supernatural - ordinary people try (or not) by love and work to give something towards.Livingstone is involved with the Sea of Faith movement, SOFIA, and edits the magazine Sofia; check it out for yourselves, even those of other faiths or none may find that interesting and valuable things are being said there.

‘Both’ is a rebuke to anyone who believes that religion and politics can ever be separated, and reminds us that the personal is indeed the political.

The goddess Astarte Ishtar Ashtoreth was the great mother. Yahweh, their male god, ordered the children of Israel to crush her utterly, smash all her shrines: she was wrong, abominable, and it was wrong to honour her. When I was young my mother went off with another man, then died of lung cancer. I was told she was in the wrong and that I should not miss her but I did. I wanted both a mother and a father.The intersection and interaction between human action, belief, and faith is further explored in poems where cold weather in the now brings back memories of a cold stepmother in the past, including a series of three untitled sonnets, ‘Keeping Faith’ . The first asks

So are you faithless if you be yourself, believe in life on Earth and humankind? Aren’t faith and hope and love a constant quest to fumble through and struggle to fulfil, embody an idea you have in mind?while the second, ‘Two Women’ is a dialogue about the nature of the self, and whether we even have a ‘self’. In reply to whether knowing we have a self is ‘just selfishness’ the reply is

No, it’s your good luck, keeps you alive. Self-seeking is the curse of selflessness but you speak for yourself. At least, that’s more.The third sonnet expresses at least part of Livingstone’s personal theology, a version of faith that has no use for supernatural beings, and asks

Can’t faith in the divine vision also thrive, now grown into a more mature poetic tale, becoming what was in it all the time?There are also a range of more ‘domestic’ or ‘nature’ poems, including ‘Nature and Grace’ where we get a story about Livingstone’s first paid translation, and her then husband’s reaction on learning that she spent the money on a new washing machine

My husband was angry. ‘You should have consulted me.’ he said, ‘it’s our money.’ I replied ‘It’s our washing.’ He looked bewildered, the idea had not occurred.The Prologue to the six poems of the sequence asks

How could a disembodied spirit speak or dance or sing the paradox, the power, the passing and the truth of human hearts?Voices, voicing, what it means to be human, and have an embodied voice, are at the heart of this book, and births, human or other, feature prominently. Livingstone’s children also feature, as well as poems set in her neighbourhood, where she says of a builder, in the poem ‘Work’

I don’t tell him I saw him heroic, the personification of Work, builder of cities, as is Love.In ‘Love’, she quotes St. Augustine and William Morris

My love is my weight, Augustine said, my gravity. We fall in love, and it is personal.She goes on to quote Morris’s John Ball’s words that ‘fellowship is life and lack of fellowship / is death.’ In stanza 4, she says

love is what we cannot do without, love builds the city through accumulation of encounters - chats in the corner shop, friends, kindred spirits and darlings of your heart - creating a habitat, a home that is a lit galaxy like the stars above but with consciousness and feeling, attraction that is wholly human.This is the voice of lived experience, and a lifetime’s devotion to the craft of making poems, informed by a unity of political belief and theology. There are poems of acceptance of bodily ageing to follow, such as ‘Ageing’ and ‘Death and After’, and in ‘Sleep Sealed’, the joy of receiving an unexpected Christmas present. The book closes with ‘The Dance’, and its last words are

Let hope or heart not fail and the dance go on. Thank you Life.Here is the voice of Sophia, female wisdom, speaking words of love, fellowship, and reminding us that as fellow creatures, we stand or fall together, but acting together in Love, we can indeed build that City.

One last thing; as regular readers will know, I am sometimes dismayed by poorly produced and badly typeset books from publishers who have apparently never troubled to read Hart’s Rules. I am pleased to say that Embodiment, like all Katabasis books, is a properly printed and handsome book with an attractive and distinctive look. This book deserves to make a window display in Waterstones Camden High St. shop.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2019 0 • Tags: books, Brian Docherty, poetry