Kevin Saving is pleased to observe Alison Brackenbury’s poetry continuing to reach new heights.

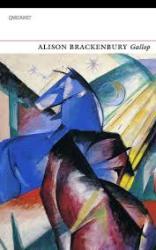

Gallop – Selected Poems

Alison Brackenbury

Carcanet

ISBN: 978 1 784106 95 9

216pp £11.69

Gallop – Selected Poems

Alison Brackenbury

Carcanet

ISBN: 978 1 784106 95 9

216pp £11.69

‘Development’ seems – or, at least used to seem to be – one of those characteristics that ‘name’ poets ought to possess. Not that there is much discernible evidence of it in, say, the poetry of Thomas Hardy (but, then, he was a ‘one-off’). Critics cherish a recognisable ‘journey’ – if only because it allows us to congratulate ourselves on our own extraordinary powers of perception. This, second, Selected from Alison Brackenbury (the first came out as long ago as 1991) gives witness to just how far she has come during a literary career which already spans four decades.

Brackenbury gave early evidence of an aptitude for the epigrammatic, a talent displayed in this volume’s opening poem, “My Old” (about elderly relatives) which concludes ‘My old are gone from name. They flare instead/ Candles: that I do not have to light’. But’ for this critic at least, those moments of clear-edged insight were previously encountered too rarely – separated by lengthy, digressive lines, a superfluity of description or (as in the much-praised “Dreams of Power” on Arabella Stuart) lavishly-imagined, but ultimately unavailing, attempts at revivification. The earliest collections were also, to some extent, hampered by a certain politesse – not precisely a weakness in itself – which could, by virtue of the author’s determination not to tread on her readership’s toes, occasionally inhibit an advance towards the essential nub of things.

It is pleasing to report that in Brackenbury’s more recent work this slightly-mannered delicacy has been largely discarded in favour of something more persuasively down-to-earth. While she still retains her early scrupulousness (and an almost Jane-ite capacity to locate the exactly ‘right’ adjective) she has, amongst other things, acquired more ‘bite’. Apparent, too, is the enhanced technique that comes from working dedicatedly at one’s craft over a prolonged period. Her later poems are still much-exercised by the natural – and, especially, the equine – world but they nowadays display both greater pulse and impulse. This frequently manifests itself via a new-found rhythmic vitality, as can be seen in “The Beanfield’s Scent”

Its flowers' tongues ask no taxes,

Though their purple is royal; their white

Is pressed by black so pure

That noon is burned to night.

Who buys a scent called 'Beanflowers'?

Its glossy blue of leaf

Buckles, to June's sharp showers.

Best things are free and brief.

This is a poet who can hymn those meagre consolations which emanate from the knowledge that, as one ages, ‘dignity’ can become an increasingly doomed quest. A good example is in these lines from “Honeycomb”:

I wonder if I live too long

but then I taste the honeycomb,

its waxen white upon my teeth,

its liquid sun which hides beneath.

Small deities, of wind or moon,

behold me. In my shabby room

I am a god. I lick the spoon.

Alison Brackenbury has always been prolific, endowed with strong powers of observation and a good – albeit idiosyncratic – ear. Her formal felicitousness is dramatically enhanced by the realisation that it is from within its smaller confines that human wisdom most readily emerges. I had formerly rather assumed that hers was an achievement of accretion: the resolute assemblage of a body of work which was consistent in its tenderness and truthfulness as well as in its orderliness and, indeed, its very ‘ordinariness’. However, this collection allows us to appreciate an upwards qualitative curve which is remarkable in its rarity. Too many ‘promising’ poets become trapped by the understandable temptation to repeat their own earlier perceived successes. Gallop shows undeniable signs of the kind of ‘late harvest’ to which so many well-applauded poets aspire and, in regards to which, so many are destined to be disappointed.

Jul 8 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Alison Brackenbury

Kevin Saving is pleased to observe Alison Brackenbury’s poetry continuing to reach new heights.

‘Development’ seems – or, at least used to seem to be – one of those characteristics that ‘name’ poets ought to possess. Not that there is much discernible evidence of it in, say, the poetry of Thomas Hardy (but, then, he was a ‘one-off’). Critics cherish a recognisable ‘journey’ – if only because it allows us to congratulate ourselves on our own extraordinary powers of perception. This, second, Selected from Alison Brackenbury (the first came out as long ago as 1991) gives witness to just how far she has come during a literary career which already spans four decades.

Brackenbury gave early evidence of an aptitude for the epigrammatic, a talent displayed in this volume’s opening poem, “My Old” (about elderly relatives) which concludes ‘My old are gone from name. They flare instead/ Candles: that I do not have to light’. But’ for this critic at least, those moments of clear-edged insight were previously encountered too rarely – separated by lengthy, digressive lines, a superfluity of description or (as in the much-praised “Dreams of Power” on Arabella Stuart) lavishly-imagined, but ultimately unavailing, attempts at revivification. The earliest collections were also, to some extent, hampered by a certain politesse – not precisely a weakness in itself – which could, by virtue of the author’s determination not to tread on her readership’s toes, occasionally inhibit an advance towards the essential nub of things.

It is pleasing to report that in Brackenbury’s more recent work this slightly-mannered delicacy has been largely discarded in favour of something more persuasively down-to-earth. While she still retains her early scrupulousness (and an almost Jane-ite capacity to locate the exactly ‘right’ adjective) she has, amongst other things, acquired more ‘bite’. Apparent, too, is the enhanced technique that comes from working dedicatedly at one’s craft over a prolonged period. Her later poems are still much-exercised by the natural – and, especially, the equine – world but they nowadays display both greater pulse and impulse. This frequently manifests itself via a new-found rhythmic vitality, as can be seen in “The Beanfield’s Scent”

This is a poet who can hymn those meagre consolations which emanate from the knowledge that, as one ages, ‘dignity’ can become an increasingly doomed quest. A good example is in these lines from “Honeycomb”:

Alison Brackenbury has always been prolific, endowed with strong powers of observation and a good – albeit idiosyncratic – ear. Her formal felicitousness is dramatically enhanced by the realisation that it is from within its smaller confines that human wisdom most readily emerges. I had formerly rather assumed that hers was an achievement of accretion: the resolute assemblage of a body of work which was consistent in its tenderness and truthfulness as well as in its orderliness and, indeed, its very ‘ordinariness’. However, this collection allows us to appreciate an upwards qualitative curve which is remarkable in its rarity. Too many ‘promising’ poets become trapped by the understandable temptation to repeat their own earlier perceived successes. Gallop shows undeniable signs of the kind of ‘late harvest’ to which so many well-applauded poets aspire and, in regards to which, so many are destined to be disappointed.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2019 1 • Tags: books, Kevin Saving, poetry