Emma Lee picks her way through a narrative sequence by Math Jones about untangling life’s complexities

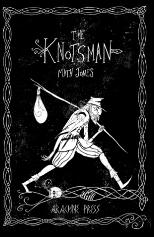

The Knotsman

Math Jones

Arachne Press

ISBN 9781909208735

112pp £9.99

The Knotsman

Math Jones

Arachne Press

ISBN 9781909208735

112pp £9.99

The Knotsman is a collection of poems about a fictional folklore character from the 17th century, with an inherited knowledge of how to untie various knots. These might be actual knots, knots that bind two people in marriage or the threads that tie people to life. It follows a narrative arc through myths about Knotsmen, the apprentice, the jobs they have taken, the itinerant nature of being a knotsman and the mastery of skills. The title poem explains the craft,

His fingers catch the smallest fibre; just a touch,

To let it know he knows it’s there;

A gentle roll to feel the threads

Within a thread, remind them each,

The twists and twills, what it feels like to be free;

Teasing, working out the strand within the tightened loop,

Pulls it clear to loose the one that’s trapped beneath.

The poem ends with the witness poet’s concerns,

I must hide my ‘scrawl’ from the Knotsman’s eye:

He’d take my tangled words, and smooth them out,

The knotted ink, to let my meaning fray.

Tied inside a Double Cobbler,

Hitched within a Secret Shank,

I keep my verse away from Knotsman’s fingers,

And I pray he will nev….

This is also a convenient explanation as to why no records exist of knotsmen. That doesn’t stop speculation as to “The First Knotsman?”

N heard agen his grannie’s rule

Of like-fer-like so boundn hopes

Began to loosen: when his man

Was dunken under, off she swam!

But taen agen, in metal hoops

They bound her tightly, brought her home.

Her proven guilt mus judgment have:

the magistrate, her sowl to save,

Said she mus ride to Neckingham!

The colloquialisms and phonetic spelling aid the sense that this is written in the style of a historical record. The suggestion that the knotsman is a descendant of women tested for witchcraft implies his craft is unwelcome and that he exists as an outsider, perhaps only revealing himself to those who understand his role. “The Weaver Wife” further cements his image as an itinerant as it suggests she traps him in a loom and becomes pregnant,

Before my mother had chance to scold him!

The baby does not cry. It sleeps,

Though with a bundled brow, as I enfold him,

And just the memory of his father seeps

Beneath my thigh. My husband starts

Beside his pretty weaver girl and in his slumber weeps.

So did he bind me in a knot?

Well, not so tight to leave me mourning what I’ve got.

“The Betrothal Rope”, a prose poem, also explores the ties of marriage where Miss J thinks she’s lost her betrothal rope and fears her husband, William, called away to war, will cheat. She is not calmed when the rope is found but instead throws it at the Knotsman,

I saw him then place that betrothal rope back into her hands. She was stiff now

with fears turned from losing William’s love to losing William’s life. The Knotsman

drew a finger down her brow. I was aholding her shoulder by now and heard his

‘Din’t mither’.

William was stiff too, beside us, head drawn back. His father’s church and teaching

was bleaker than ours, but he suffered the Knotsman to unbind a twist or two of his

over-tight chinstrap, straighten a string at his neck. ‘That’ll bring ye safe back agen,

la’,’ he said,

The Knotsman gifts both participants: William will survive war and Miss J will no longer nag him about her fears that he will be unfaithful. In a later poem, “The Poetess”, the Knotsman refuses to unknot a poem,

These lines, I cannot unbind ‘em, not ‘ere,

much less once they’re join’d to the air.

An’ now ye weep agen. I’m sore fer that.

Thy kin’ve no patience fer yer pain;

they’d call it shame. An’ I c’not unstitch

the words you’ve risted here in rhyme.

That’s the world’s now,

‘N’ ye must learn to live in it any how

ye can.

By gathering these poems as a collection rather than a straightforward narrative arc, Math Jones gives himself space to create different voices: the apprentice who is also narrator; children’s rhymes telling tales of The Knotsman; and The Knotsman’s attempts to understand his own roots by means of stories about people he has been able to help. In one instance we learn of an imposter who was able to unknot threads but failed to understand the limits of his talent and how it could not be used in jealousy or in judgment. This is a collection that can be read both in one sitting or dipped into at leisure because the poems do not need to be read in order. Through The Knotsman Math Jones has created an intriguing character and his stories have a timeless feel: they could read as straightforward historical narrative or as a metaphor for more contemporary anxieties.

May 2 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Math Jones

Emma Lee picks her way through a narrative sequence by Math Jones about untangling life’s complexities

The Knotsman is a collection of poems about a fictional folklore character from the 17th century, with an inherited knowledge of how to untie various knots. These might be actual knots, knots that bind two people in marriage or the threads that tie people to life. It follows a narrative arc through myths about Knotsmen, the apprentice, the jobs they have taken, the itinerant nature of being a knotsman and the mastery of skills. The title poem explains the craft,

The poem ends with the witness poet’s concerns,

This is also a convenient explanation as to why no records exist of knotsmen. That doesn’t stop speculation as to “The First Knotsman?”

The colloquialisms and phonetic spelling aid the sense that this is written in the style of a historical record. The suggestion that the knotsman is a descendant of women tested for witchcraft implies his craft is unwelcome and that he exists as an outsider, perhaps only revealing himself to those who understand his role. “The Weaver Wife” further cements his image as an itinerant as it suggests she traps him in a loom and becomes pregnant,

“The Betrothal Rope”, a prose poem, also explores the ties of marriage where Miss J thinks she’s lost her betrothal rope and fears her husband, William, called away to war, will cheat. She is not calmed when the rope is found but instead throws it at the Knotsman,

The Knotsman gifts both participants: William will survive war and Miss J will no longer nag him about her fears that he will be unfaithful. In a later poem, “The Poetess”, the Knotsman refuses to unknot a poem,

By gathering these poems as a collection rather than a straightforward narrative arc, Math Jones gives himself space to create different voices: the apprentice who is also narrator; children’s rhymes telling tales of The Knotsman; and The Knotsman’s attempts to understand his own roots by means of stories about people he has been able to help. In one instance we learn of an imposter who was able to unknot threads but failed to understand the limits of his talent and how it could not be used in jealousy or in judgment. This is a collection that can be read both in one sitting or dipped into at leisure because the poems do not need to be read in order. Through The Knotsman Math Jones has created an intriguing character and his stories have a timeless feel: they could read as straightforward historical narrative or as a metaphor for more contemporary anxieties.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2019 0 • Tags: books, Emma Lee, poetry