P W Bridgman confesses himself pleasantly surprised by an unorthodox combination of poetry collection and murder mystery: he promises however that his review contains no spoilers.

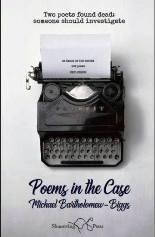

Poems in the Case

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

Shoestring Press

ISBN 978-1-912524-05-1

118pp £10

Poems in the Case

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

Shoestring Press

ISBN 978-1-912524-05-1

118pp £10

Now here’s a fascinating question to ponder: how might a murder mystery look if told in an intricate mélange of prose and verse? This is not a combined enterprise that is easy to imagine, at least not at first. Indeed, one might speculate (perhaps unfairly) that readers of crime fiction and readers of poetry have very little in common; that they must surely huddle in separate circles in the Great Literary Venn Diagram with only a lonely few clustered together in the intersection space. Certainly, Poems in the Case situates Michael Bartholomew-Biggs—a mathematician and a respected poet—squarely within that intersection space. More of us should join him there. In this reviewer’s opinion, his latest book ought to have the salutary effect of opening poetically tuned minds to crime fiction and mystery novel-tuned minds to poetry.

Poems in the Case is without doubt an innovation and an experiment; indeed, it is a noble experiment. Bartholomew-Biggs and his publisher Shoestring Press are to be commended for striking out into new and almost entirely uncharted territory. Of course, innovation and experiment always carry a measure of risk. Even noble experiments can fail miserably. That has not happened with this noble experiment, however. Given generally to observing crime fiction warily and from a safe distance, your Canadian reviewer will admit that he approached Poems in the Case with some foreboding. However, after a few pages that foreboding fell away. Completely. If you give it a chance this “genre-bending” book (as the publisher’s jacket copy styles it) will quickly bring you, too, under its spell and then carry you along, quite possibly from page 1 to page 118 without pausing for a break.

Seldom when reviewing poetic works does a reviewer have to concern him- or herself about giving something away. But Poems in the Case is not just a selection of poetry; its well-wrought poems are interwoven with deftly written prose. Together, they combine to trace a narrative arc along which, slowly, important plot elements come into focus the way the features of a black-and-white photograph come into focus as it lies submerged in a developing bath. Accordingly, out of respectful deference to the author and his readers, care must be taken by this and all reviewers not to break the spell.

That said, at least a skeletal outline of the book can safely be given. Poems in the Case characters George Hamblin and now deceased Eric Jessop were once poets and lovers. Sometime after Jessop dies in a tumble down a cliff in coastal Devon—an apparent suicide driven by an apparent bout of depression after an apparently intractable spell of writers’ block—a body of Jessop’s unpublished poems surfaces. Stephen Prince, the principal of Epidermis Press (Jessop’s publisher), announces his intention to bring out those poems posthumously. There is a question as to whether the poems were written earlier in Jessop’s life and went unnoticed, or nearer to the time of his death. Hamblin is rightly unnerved and apprehensive about their imminent release.

Meanwhile, not entirely by coincidence, Prince and Hamblin find themselves in competition for a prestigious and handsomely funded poet-in-residence post with… wait for it… an investment company called McMahon Associates (“often called ‘Mammon’”). The decision-makers on McMahon’s “Cultural Capital (Poetry) Panel” are divided and hence undecided; they see merit in both candidates but for different reasons:

Some thought Hamblin’s cosily nostalgic verses carried reassuring implications of

investor security while others felt that Prince’s darker, edgier poems suggested

positive ideas of enterprise and profitable risk-taking.

Ah. Poetry as seen through the foggy lens of the merchant banker and the hedge fund manager, displayed figuratively on an Excel spreadsheet; monetised, amortised, sterilised and contextualised by profits, losses, returns on investment and deferred taxes. Don’t you just love it? (This is a perspective that likely would be shared by the aggressively left-leaning poet Seth Buckler, who appears later in the story.) One cannot help but be reminded of Allen Ginsberg’s persistent “Moloch” lament in Howl:

…Moloch whose eyes are a thousand blind windows! Moloch whose skyscrapers

stand in the long streets like endless Jehovahs! Moloch whose factories dream and

croak in the fog! Moloch whose smoke-stacks and antennae crown the cities!

With McMahon’s decision as to who will receive the coveted poet-in-residence post still pending, the two contenders find themselves, to their surprise and mild annoyance, invited to lead, as joint tutors, a pricey, week-long, residential poetry workshop entitled “Delighting in the Dark Side”. Admission to the program is based upon applications consisting mainly of samples of the hopeful participants’ written work. Ultimately, six aspiring poets are chosen. They gather at a bucolic Wealden retreat property in Kent administered by the enigmatic Julia. Weald Barn’s operations are fittingly funded in part by a “legacy from a literary-minded manufacturer of tomato sauce”.

As can be seen, Bartholomew-Biggs plainly enjoys juxtaposing the sacred against the profane. Alongside everything else, Poems in the Case abounds with deliciously dark humour. Consider this clever and mildly transgressive haiku, penned by the author in the voice of a sexist and deeply insecure workshop registrant:

Mouth still full of fruit

Eve said to Adam ‘You need

a bigger fig leaf.’

And what about this mocking emulation of country and western song lyrics found in a poem attributed to the workshop’s expat Canadian participant?

Dust is rising up beside the highway

where a John Deere tractor grumbles by;

but since your Dear John letter headed my way

dust is not the thing that stings my eye

and blurs Alberta highway to a cry-way

through a windshield streaked and smeared with tears.

The road I’m riding now is a goodbye-way

that runs from all our happy years

This would have been a straight and clear dry-eye way

if only I’d been driving back to you;

but I’ve detoured onto a groan-and-sigh way—

one bad mistake means you and I are through…

So cringeworthy. And so, so savagely brilliant! (Although they might not agree with this assessment in Red Deer or any of the other locations named in the lyrics.)

One can quickly see as one progresses through Poems in the Case that with competitive and other tensions already rising between Prince and Hamblin, the week-long writers retreat is ripe with potential for pointed one-upmanship, if not more, in the interactions between the tutors. Stir into the beaker the curious mix of fragile and unjustifiably robust egos reflected in the group of registrants and the alchemical possibilities seem endless.

Bartholomew-Biggs skilfully provides his readers with some initial details about the attributes of the six workshop participants by setting out poems from each of their respective application packages. The reasons why all were attracted to a workshop with the theme “Delighting in the Dark Side” become quickly evident. The registrants comprise a quirky assemblage of poets “with issues” (as they say nowadays). The author has adroitly set the stage for some sinister, interpersonal conflict between the tutors, between and amongst the registrants, and between the tutors and the registrants.

Remarkably, the hard work in advancing the plot of this fine book has been done mostly through the poems. The interstitial spaces between them are filled with comparatively spare, prose narrative passages that serve as connective tissue. One senses, from the book’s conceptual architecture alone, that deeply intelligent and innovative artistry is on display here. Page by page, the intermingled poetry and prose in Poems in the Case reveal, by degrees, more about the characters gathered together at Weald Barn for the “Delighting in the Dark Side” retreat, about their back stories and about some unlikely factors that link some to others and to Jessop. Through nuance and indirection, sly hints and clues signalling what is to come gradually accumulate as participants present and “workshop” their writing. Vanities, idiosyncrasies, eccentricities and secrets emerge, little by little. Bartholomew-Biggs succeeds masterfully in giving each of his eight characters individual voices through their poetry. One quickly begins to recognise which of those characters has written which of the poems without needing to look for explicit attribution.

So now the dilemma has been reached and it must be faced. Where to go from here? How much more can a reviewer of Poems in the Case safely say without imperilling the future reader’s enjoyment of the book? It is by accretion after all, through a tantalisingly slow creep even, that this artful volume carries the reader forward through a succession of subtle revelations to its conclusion. It would be unforgivable if those incremental pleasures were to be compromised or undermined by spoiler content in this review. That line simply must not be crossed. And so it shall not be.

It is hoped that enough has been said here to induce the curious to rush out and purchase their own copies of Poems in the Case and permit themselves to be caught up and then carried along the circuitous pathway it traces. There is sustenance aplenty in these pages for devoted readers of poetry and devoted readers of crime fiction. Wary members of both camps who generally eschew fraternisation with one another simply must suspend judgment and give Bartholomew-Biggs’ unique, hybrid creation a try. Far from not being disappointed, they will be positively gob-smacked.

Mar 3 2019

Poems in the Case

P W Bridgman confesses himself pleasantly surprised by an unorthodox combination of poetry collection and murder mystery: he promises however that his review contains no spoilers.

Now here’s a fascinating question to ponder: how might a murder mystery look if told in an intricate mélange of prose and verse? This is not a combined enterprise that is easy to imagine, at least not at first. Indeed, one might speculate (perhaps unfairly) that readers of crime fiction and readers of poetry have very little in common; that they must surely huddle in separate circles in the Great Literary Venn Diagram with only a lonely few clustered together in the intersection space. Certainly, Poems in the Case situates Michael Bartholomew-Biggs—a mathematician and a respected poet—squarely within that intersection space. More of us should join him there. In this reviewer’s opinion, his latest book ought to have the salutary effect of opening poetically tuned minds to crime fiction and mystery novel-tuned minds to poetry.

Poems in the Case is without doubt an innovation and an experiment; indeed, it is a noble experiment. Bartholomew-Biggs and his publisher Shoestring Press are to be commended for striking out into new and almost entirely uncharted territory. Of course, innovation and experiment always carry a measure of risk. Even noble experiments can fail miserably. That has not happened with this noble experiment, however. Given generally to observing crime fiction warily and from a safe distance, your Canadian reviewer will admit that he approached Poems in the Case with some foreboding. However, after a few pages that foreboding fell away. Completely. If you give it a chance this “genre-bending” book (as the publisher’s jacket copy styles it) will quickly bring you, too, under its spell and then carry you along, quite possibly from page 1 to page 118 without pausing for a break.

Seldom when reviewing poetic works does a reviewer have to concern him- or herself about giving something away. But Poems in the Case is not just a selection of poetry; its well-wrought poems are interwoven with deftly written prose. Together, they combine to trace a narrative arc along which, slowly, important plot elements come into focus the way the features of a black-and-white photograph come into focus as it lies submerged in a developing bath. Accordingly, out of respectful deference to the author and his readers, care must be taken by this and all reviewers not to break the spell.

That said, at least a skeletal outline of the book can safely be given. Poems in the Case characters George Hamblin and now deceased Eric Jessop were once poets and lovers. Sometime after Jessop dies in a tumble down a cliff in coastal Devon—an apparent suicide driven by an apparent bout of depression after an apparently intractable spell of writers’ block—a body of Jessop’s unpublished poems surfaces. Stephen Prince, the principal of Epidermis Press (Jessop’s publisher), announces his intention to bring out those poems posthumously. There is a question as to whether the poems were written earlier in Jessop’s life and went unnoticed, or nearer to the time of his death. Hamblin is rightly unnerved and apprehensive about their imminent release.

Meanwhile, not entirely by coincidence, Prince and Hamblin find themselves in competition for a prestigious and handsomely funded poet-in-residence post with… wait for it… an investment company called McMahon Associates (“often called ‘Mammon’”). The decision-makers on McMahon’s “Cultural Capital (Poetry) Panel” are divided and hence undecided; they see merit in both candidates but for different reasons:

Ah. Poetry as seen through the foggy lens of the merchant banker and the hedge fund manager, displayed figuratively on an Excel spreadsheet; monetised, amortised, sterilised and contextualised by profits, losses, returns on investment and deferred taxes. Don’t you just love it? (This is a perspective that likely would be shared by the aggressively left-leaning poet Seth Buckler, who appears later in the story.) One cannot help but be reminded of Allen Ginsberg’s persistent “Moloch” lament in Howl:

With McMahon’s decision as to who will receive the coveted poet-in-residence post still pending, the two contenders find themselves, to their surprise and mild annoyance, invited to lead, as joint tutors, a pricey, week-long, residential poetry workshop entitled “Delighting in the Dark Side”. Admission to the program is based upon applications consisting mainly of samples of the hopeful participants’ written work. Ultimately, six aspiring poets are chosen. They gather at a bucolic Wealden retreat property in Kent administered by the enigmatic Julia. Weald Barn’s operations are fittingly funded in part by a “legacy from a literary-minded manufacturer of tomato sauce”.

As can be seen, Bartholomew-Biggs plainly enjoys juxtaposing the sacred against the profane. Alongside everything else, Poems in the Case abounds with deliciously dark humour. Consider this clever and mildly transgressive haiku, penned by the author in the voice of a sexist and deeply insecure workshop registrant:

And what about this mocking emulation of country and western song lyrics found in a poem attributed to the workshop’s expat Canadian participant?

So cringeworthy. And so, so savagely brilliant! (Although they might not agree with this assessment in Red Deer or any of the other locations named in the lyrics.)

One can quickly see as one progresses through Poems in the Case that with competitive and other tensions already rising between Prince and Hamblin, the week-long writers retreat is ripe with potential for pointed one-upmanship, if not more, in the interactions between the tutors. Stir into the beaker the curious mix of fragile and unjustifiably robust egos reflected in the group of registrants and the alchemical possibilities seem endless.

Bartholomew-Biggs skilfully provides his readers with some initial details about the attributes of the six workshop participants by setting out poems from each of their respective application packages. The reasons why all were attracted to a workshop with the theme “Delighting in the Dark Side” become quickly evident. The registrants comprise a quirky assemblage of poets “with issues” (as they say nowadays). The author has adroitly set the stage for some sinister, interpersonal conflict between the tutors, between and amongst the registrants, and between the tutors and the registrants.

Remarkably, the hard work in advancing the plot of this fine book has been done mostly through the poems. The interstitial spaces between them are filled with comparatively spare, prose narrative passages that serve as connective tissue. One senses, from the book’s conceptual architecture alone, that deeply intelligent and innovative artistry is on display here. Page by page, the intermingled poetry and prose in Poems in the Case reveal, by degrees, more about the characters gathered together at Weald Barn for the “Delighting in the Dark Side” retreat, about their back stories and about some unlikely factors that link some to others and to Jessop. Through nuance and indirection, sly hints and clues signalling what is to come gradually accumulate as participants present and “workshop” their writing. Vanities, idiosyncrasies, eccentricities and secrets emerge, little by little. Bartholomew-Biggs succeeds masterfully in giving each of his eight characters individual voices through their poetry. One quickly begins to recognise which of those characters has written which of the poems without needing to look for explicit attribution.

So now the dilemma has been reached and it must be faced. Where to go from here? How much more can a reviewer of Poems in the Case safely say without imperilling the future reader’s enjoyment of the book? It is by accretion after all, through a tantalisingly slow creep even, that this artful volume carries the reader forward through a succession of subtle revelations to its conclusion. It would be unforgivable if those incremental pleasures were to be compromised or undermined by spoiler content in this review. That line simply must not be crossed. And so it shall not be.

It is hoped that enough has been said here to induce the curious to rush out and purchase their own copies of Poems in the Case and permit themselves to be caught up and then carried along the circuitous pathway it traces. There is sustenance aplenty in these pages for devoted readers of poetry and devoted readers of crime fiction. Wary members of both camps who generally eschew fraternisation with one another simply must suspend judgment and give Bartholomew-Biggs’ unique, hybrid creation a try. Far from not being disappointed, they will be positively gob-smacked.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, fiction, poetry reviews, year 2019 0 • Tags: books, fiction, P W Bridgman, poetry