Adele Ward admires the skill with which Kate Davis’s complex debut collection has been put together

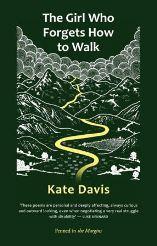

The Girl Who Forgets How to Walk

Kate Davis

Penned in the Margins, 2018

ISBN: 9781908058515

88pp £9.99

The Girl Who Forgets How to Walk

Kate Davis

Penned in the Margins, 2018

ISBN: 9781908058515

88pp £9.99

This is a remarkably self-assured debut by a poet who knows what she wishes to achieve and accomplishes her aims, both in terms of theme and form. The title is taken from the book’s long central section, which follows the experiences of a young girl who contracts polio, a subject that Davis treats with a mixture of scientific knowledge, emotional poignancy and the beauty of art applied to unexpected subjects.

By contrast, the opening section has poems that are frequently devoid of human presence, showing instead a deep geological knowledge of how landscape is formed, particularly the type of landscape that erodes or caves in, causing sinkholes that can swallow people, their homes and belongings. This movement from part one to part two is effective, taking the reader from a sense of instability in the ground under their feet, to the main sequence with its depiction of a physical condition that arrives suddenly and quite literally leaves a girl unable to walk.

In the third section the ideas of the first two parts are brought together, with geology and anatomy combined in metaphors and imagery that have been sustained throughout the collection. This sequential approach, with many poems working well on their own as well as contributing to the developing narrative, permits the poet to experiment with form in order to approach the subject from different angles and in an impressive variety of styles.

Davis’s poetry is described on the cover as ‘magic realism’, although it is also realistic and scientific. Poetry could often be described as magic realism, as readers are familiar with metaphors that merge and transform the subjects described, and there are certainly some poems where Davis uses a surreal approach. For example, in “Relativity” a street is being knocked down and the poet describes seeing ‘a woman / in clear space ten feet above the rubble / lift her hem to button a shoe’, while a man ‘asleep in mid-air turned over’. Are these imagined characters, the previous inhabitants of the houses, or has a wall fallen away and exposed them? The result is unsettling, rather like the seemingly surreal but factually accurate descriptions in the war poetry of Brian Turner, where ordinary roads are scattered with limbs and even a disembodied moustache after an explosion.

In some poems Davis uses a fairytale approach, although I wouldn’t want to limit the stylistic range of this poet by calling the collection magic realism. In “Grim”, a title reminiscent of the Grimm brothers, the poem is in the style of Hilaire Belloc and warns: ‘Don’t go down to the tarn children, / don’t go down to the tarn’ because ‘Ginny Green Teeth is there’. This witch-like figure will

… drag you down by your hair, children

down in the cold, red water,

she’ll drown you with your own hair.

The cautionary tale approach combined with fairytale characters in this poem may be a kind of magic realism, but this will lead to scientific and realistic echoes in the central section, where a young girl goes swimming on holiday not knowing that ‘the sea hid a gob of virus’ and that ‘the virus intended to get to the core of her spine’ (“How the forgetting began”). The reality is as fearsome as Ginny Green Teeth.

“Grim” is preceded by a found poem called “Tarn”, adapted from a textbook passage describing a village by a tarn and relating local superstitions about subsidence, flooding and an earthquake anecdotally caused by women taunting the priests. Facts and fears in “Tarn” chime with the fairytale tarn in “Grim”, while water links these with many other poems in the collection, including the sea that is at times beautiful but also contains the polio virus that will take away the girl’s ability to walk.

Found poems provide factual information, such as the formation of limestone in “Limestone CaCO3)”, which is adapted from a scientific text. These found poems are presented in a narrow, newspaper column style format, and would not work on their own but are effective as ways of informing the other poems in the collection. There’s a music to the way the poems work together and strengthen each other, including recurrent imagery as well as subject matter and narrative.

The use of found poems reaches a climax in the central section with the striking poem “The complete mechanisation of the post infectious child”. The text for this poem is referenced as an ‘Extract from Hayne’s Workshop Manual Series’ and it describes the fitting of callipers to a child in terms that lead to complete objectification and dehumanisation. Unlike the other found poems in newspaper column style, this one has line breaks and somehow the lack of emotion in the instructions makes it all the more moving:

With child face up measure and mark

attachment positions for calliper system(s).

Turn child over. Repeat.

Secure child in clamp and drill as marked.

Fit pre-assembled calliper system(s)

to affected limb(s)

tightening opposite screws in turn.

Tighten limit screws.

Poetry set in hospitals can be particularly dreary, but at its best, as it is in this collection, it can be original and startling as well as moving. Sometimes the poems are plain spoken and understated but bring the child’s experience vividly to life:

The green room with the gowns and masks

is a place where people only pass through,

in and out like ants, like bees;

they press her feet, they bend her knees,

they shake their heads, they walk away.

(“The cot in the isolation hospital”)

At other times Davis mixes this everyday realism with the scientific and fairytale approaches of previous poems, creating a frightening vision seen through the eyes of the child. This is particularly effective in “The Ethel Hedley Hospital for Crippled Children” where the child is fascinated by ‘The Iron Lung Girls’ who have ‘done away with the need / for ankle socks and sandals.’

Davis is deft in the use of carefully selected descriptions that let the reader imagine these girls, who ‘clock her in their mirrors / whenever she comes in.’ This inability to move, able only to see via mirrors, captures their condition with pitiful precision for the reader, but turns them into mythological and fearful beings for the girl.

Davis’s language moves seamlessly from the understated into striking metaphors, such as ‘The bodies of the Iron Lung Girls are canals; / stagnant inside their breathing machines’ and ‘The voices of the Iron Lung Girls / are push-bikes sluicing Stretford wet; // they unroll words confident as new lino.’

Many of the poems are worthy of quotation, and every poem deserves its place. There are also experiments in form, with poems that play with white space, fragmented lines, and even single-word lines, to emulate the child’s tentative movements towards regaining the ability to walk. The unstable land of the opening section, followed by the child’s physical condition in the central section, draw the reader in so that we are following each difficult step by the time we reach the poem “She teaches herself to walk across a limestone landscape”:

Start

check

step

check

step

slope

slip stop

stop stop stop

This poem ends with the simple words ‘step step step step step’ and we are right there, willing the girl to succeed in her painstaking progress.

The overall effect of the book is one of hope and the determination not only to survive but to thrive, although there is no Panglossian attempt to avoid the stark experiences of physical and emotional suffering, including bullying. Language is seen as having a saving ability, especially in the poem “Thesaurus for a Lady Gum-Shoe”, which uses a humorous private detective narrative and voice to show the search for words and behaviours than can help the vulnerable avoid ambush. Words like ‘Abnormal Aberration Ugly’ are replaced at the end of the poem by words including ‘Acceptable Consistent Equal’. Although this stops the old bullying words being ‘such tough guys’, the character now grown older is still watchful and must ‘keep a look-out’.

The Girl Who Forgets How to Walk has clearly taken years to write, as has the ordering of the poems into a sequence that leads to them resonating together and strengthening each other. The time and effort have paid off and I look forward to reading more by this poet.

Mar 26 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Kate Davis

Adele Ward admires the skill with which Kate Davis’s complex debut collection has been put together

This is a remarkably self-assured debut by a poet who knows what she wishes to achieve and accomplishes her aims, both in terms of theme and form. The title is taken from the book’s long central section, which follows the experiences of a young girl who contracts polio, a subject that Davis treats with a mixture of scientific knowledge, emotional poignancy and the beauty of art applied to unexpected subjects.

By contrast, the opening section has poems that are frequently devoid of human presence, showing instead a deep geological knowledge of how landscape is formed, particularly the type of landscape that erodes or caves in, causing sinkholes that can swallow people, their homes and belongings. This movement from part one to part two is effective, taking the reader from a sense of instability in the ground under their feet, to the main sequence with its depiction of a physical condition that arrives suddenly and quite literally leaves a girl unable to walk.

In the third section the ideas of the first two parts are brought together, with geology and anatomy combined in metaphors and imagery that have been sustained throughout the collection. This sequential approach, with many poems working well on their own as well as contributing to the developing narrative, permits the poet to experiment with form in order to approach the subject from different angles and in an impressive variety of styles.

Davis’s poetry is described on the cover as ‘magic realism’, although it is also realistic and scientific. Poetry could often be described as magic realism, as readers are familiar with metaphors that merge and transform the subjects described, and there are certainly some poems where Davis uses a surreal approach. For example, in “Relativity” a street is being knocked down and the poet describes seeing ‘a woman / in clear space ten feet above the rubble / lift her hem to button a shoe’, while a man ‘asleep in mid-air turned over’. Are these imagined characters, the previous inhabitants of the houses, or has a wall fallen away and exposed them? The result is unsettling, rather like the seemingly surreal but factually accurate descriptions in the war poetry of Brian Turner, where ordinary roads are scattered with limbs and even a disembodied moustache after an explosion.

In some poems Davis uses a fairytale approach, although I wouldn’t want to limit the stylistic range of this poet by calling the collection magic realism. In “Grim”, a title reminiscent of the Grimm brothers, the poem is in the style of Hilaire Belloc and warns: ‘Don’t go down to the tarn children, / don’t go down to the tarn’ because ‘Ginny Green Teeth is there’. This witch-like figure will

… drag you down by your hair, children down in the cold, red water, she’ll drown you with your own hair.The cautionary tale approach combined with fairytale characters in this poem may be a kind of magic realism, but this will lead to scientific and realistic echoes in the central section, where a young girl goes swimming on holiday not knowing that ‘the sea hid a gob of virus’ and that ‘the virus intended to get to the core of her spine’ (“How the forgetting began”). The reality is as fearsome as Ginny Green Teeth.

“Grim” is preceded by a found poem called “Tarn”, adapted from a textbook passage describing a village by a tarn and relating local superstitions about subsidence, flooding and an earthquake anecdotally caused by women taunting the priests. Facts and fears in “Tarn” chime with the fairytale tarn in “Grim”, while water links these with many other poems in the collection, including the sea that is at times beautiful but also contains the polio virus that will take away the girl’s ability to walk.

Found poems provide factual information, such as the formation of limestone in “Limestone CaCO3)”, which is adapted from a scientific text. These found poems are presented in a narrow, newspaper column style format, and would not work on their own but are effective as ways of informing the other poems in the collection. There’s a music to the way the poems work together and strengthen each other, including recurrent imagery as well as subject matter and narrative.

The use of found poems reaches a climax in the central section with the striking poem “The complete mechanisation of the post infectious child”. The text for this poem is referenced as an ‘Extract from Hayne’s Workshop Manual Series’ and it describes the fitting of callipers to a child in terms that lead to complete objectification and dehumanisation. Unlike the other found poems in newspaper column style, this one has line breaks and somehow the lack of emotion in the instructions makes it all the more moving:

With child face up measure and mark attachment positions for calliper system(s). Turn child over. Repeat. Secure child in clamp and drill as marked. Fit pre-assembled calliper system(s) to affected limb(s) tightening opposite screws in turn. Tighten limit screws.Poetry set in hospitals can be particularly dreary, but at its best, as it is in this collection, it can be original and startling as well as moving. Sometimes the poems are plain spoken and understated but bring the child’s experience vividly to life:

The green room with the gowns and masks is a place where people only pass through, in and out like ants, like bees; they press her feet, they bend her knees, they shake their heads, they walk away. (“The cot in the isolation hospital”)At other times Davis mixes this everyday realism with the scientific and fairytale approaches of previous poems, creating a frightening vision seen through the eyes of the child. This is particularly effective in “The Ethel Hedley Hospital for Crippled Children” where the child is fascinated by ‘The Iron Lung Girls’ who have ‘done away with the need / for ankle socks and sandals.’

Davis is deft in the use of carefully selected descriptions that let the reader imagine these girls, who ‘clock her in their mirrors / whenever she comes in.’ This inability to move, able only to see via mirrors, captures their condition with pitiful precision for the reader, but turns them into mythological and fearful beings for the girl.

Davis’s language moves seamlessly from the understated into striking metaphors, such as ‘The bodies of the Iron Lung Girls are canals; / stagnant inside their breathing machines’ and ‘The voices of the Iron Lung Girls / are push-bikes sluicing Stretford wet; // they unroll words confident as new lino.’

Many of the poems are worthy of quotation, and every poem deserves its place. There are also experiments in form, with poems that play with white space, fragmented lines, and even single-word lines, to emulate the child’s tentative movements towards regaining the ability to walk. The unstable land of the opening section, followed by the child’s physical condition in the central section, draw the reader in so that we are following each difficult step by the time we reach the poem “She teaches herself to walk across a limestone landscape”:

This poem ends with the simple words ‘step step step step step’ and we are right there, willing the girl to succeed in her painstaking progress.

The overall effect of the book is one of hope and the determination not only to survive but to thrive, although there is no Panglossian attempt to avoid the stark experiences of physical and emotional suffering, including bullying. Language is seen as having a saving ability, especially in the poem “Thesaurus for a Lady Gum-Shoe”, which uses a humorous private detective narrative and voice to show the search for words and behaviours than can help the vulnerable avoid ambush. Words like ‘Abnormal Aberration Ugly’ are replaced at the end of the poem by words including ‘Acceptable Consistent Equal’. Although this stops the old bullying words being ‘such tough guys’, the character now grown older is still watchful and must ‘keep a look-out’.

The Girl Who Forgets How to Walk has clearly taken years to write, as has the ordering of the poems into a sequence that leads to them resonating together and strengthening each other. The time and effort have paid off and I look forward to reading more by this poet.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2019 0 • Tags: Adele Ward, books, poetry