John Forth appreciates the sense of knowledge and information worn lightly that runs through the poetry of Tony Roberts

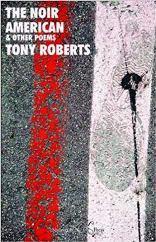

The Noir American & Other Poems

Tony Roberts

Shoestring Press, 2018

ISBN 9781912 524150

74pp £10.00

The Noir American & Other Poems

Tony Roberts

Shoestring Press, 2018

ISBN 9781912 524150

74pp £10.00

Someone said once that we must distinguish between those who collect records and those who play them. Although I’d come across a few people who do both, I knew that an important distinction was being made and that it referred to more than music. Tony Roberts plays records and dreams of playing on them, and the dream washes over all he writes. In fact I’d been trying to keep up with mid-twentieth century jazz history with the small batches of poems at the end of his last two collections, six poems in all, but now I see he was being flexible with the chronology of the period if not with its stellar names. He was doing the same with his thorough knowledge of Shakespeare – because the guy at the centre of all this is Ty ‘Prince’ Dove, a fictional Hamlet-obsessed wannabe tenor saxman who’s bouncing off real legends from the period and who could boast a childhood to rival that of the Prince himself:

The Prince's tragedy lies otherwise

and here it is without the candy shell:

he sprang a leak at one face in the crowd,

the mirror of his longago Daddy...

the poem going on to tell of his uncle’s marrying his mother ‘in unseemly haste’ while the Prince (plain ‘Ty Dove’ then):

...stands for centuries beside

the shabby juke box in their shady bar

playing with the music for loose change.

[“After Locking Horns with Dexter”].

What really works for Roberts is the adoption of a lingo we associate with the period sustained in 4 and 5-beat lines that might be Chandler if it wasn’t jazz. I’m completely taken-in by the subterfuge. The original ‘Noir Américain’ translates as ‘American Black’, so Ty is black and also slightly ‘noir’ in the shadowy black & white sense – since ‘color’s just another fucked up way / of seeing things’ (“Prologue: Le Noir Américain”). Roberts grabs the best of all worlds when he translates his title from the French of a black woman in “The Other Side of Midnight” into American English as ‘black american’. However it’s translated, it’s good to see the original six poems take centre stage along with a few more to form “The Noir American”.

And it really does seem that this particular devil’s music has the best lines, because Roberts borrows a lot of them. The joke about a drummer asking ‘Pres’ (Lester Young) when they last played together and getting the answer ‘Tonight’; Bird telling Ty during the latter’s overblown debut ‘don’t just do something, my man, stand there’ and then going on to offer a tough aesthetic: ‘Hey, don’t you know that it’s respect that kills? / Be bold; be resolute – and don’t play me’ (“How He Jams with Bird and Hits the Water Running”). When ‘Dex’ (-ter Gordon) dreams of exile it’s because we’ve already been told that ‘Paris is Disneyland’ with quips and gags that serve to set a tone and keep it: ‘Go mingle with the Gallic epicures / advises Dexter.’ (“After Locking Horns with Dexter”). Ty himself has more than a few good lines too: when he tells a waitress who dreams of singing like Sarah Vaughan that ‘in their world/ the only way to wind up with a million / is to start with two.’ (“In which he Arrives in the Big Apple & Meets his Lady over Coffee”) – or when he addresses a noisy naval crew in a bar with a Mingus jibe: ‘Ladies, mariners, gentlemen, it’s come /to our attention you’re not getting / what you paid for, and we sure as shit / ain’t getting your attention…’ (“An Audience with the Prince”). This episode shows him running out of puff for the American scene and readying himself for a return to Paris whence he came: ‘But don’t go telling him the Big Bad Wolf / ain’t out there, because the Prince has seen its tracks’, one of several references to the drug scene. It feeds nicely into Ty’s fantasy of harnessing his own talent to that of Bill Evans who is ‘almost too cerebral’ (“Of Howling at the Moon & Digging Bill Evans”). The whole story is a chaotic bone-shaking vehicle of fact and fiction in which real characters fade in and out of recognition as it runs on its own momentum.

So, suddenly, we’re back in Paris with ‘this clued-up chick’ called Sabine who springs him from an institution where he’s being shrunk and confined for displaying too much wildness. She has an uproarious dream in which the joint fills up with famous thinkers who end up starting a bar-brawl, but at least here ‘he’s treated like an artist/ not a horn-blower’. He seems to be tasting happiness and ends by telling her she’s become his muse, but she’s having none of it: ‘Muse, my ace, she says’ (“Which Treats of Sabine’s Dream of Camus with the Prince Playing Along”). Then he’s back at Birdland, truly picaresque now, in a crisis (“He’s Hamleting”) – needing to catch up on what’s been going on while he’s been gone – and we’re becoming more aware of the problem of exile without being sure in which place he feels it the most (“On Being Back at Birdland”). There’s a moving tribute to Billie Holiday which almost breaks stride with the other poems, being a stream-(of death)-consciousness with Pres dying the same year: ‘She must have played / a thousand joints that wouldn’t let her in / except as hired help’ (“Where He Sings the Blues for Lady Day”). By the final poem he has become ‘an internal exile’ like the rest of them and in this sense the poem surely reaches beyond its own nutshell:

The English call it barking mad, this urge

to put oneself through shit, time and again.

Yet what can he – most sleek and quarrelsome – do

other than cement his reputation as

The Prince of Cats.

[“Enter as Prince”]

There are now thirteen long(ish) poems evolved from the original six, and at 35 pages it’s half the book. Great fun, supported by moments of great seriousness, and probably yielding more to jazz experts than I’m mustering here. Shakespeare (and not just Hamlet) references surface casually all the time and the pot-pourri certainly persuades me. I imagine it will work for them too.

The second half of the book is sub-titled ‘other lyrics’ and here we find Roberts’ familiar mix of historical and artistic contexts that are always rendered ‘personal’ in the truest sense. The poems are not afraid to be complex but always glad to keep things simple – there’s a long and cheering monologue from RLS admiring Sargent’s portrait of the family (“At Skerryvore”) and, in “Theatre”, a moment frozen from the end of The Seagull:

Shamrayev and Polina hold the look

they have exchanged, while Masha's fingers

lace her cheek. I close my eyes against

the house lights and the actors selling out

their characters for a handful of applause.

Not all of the personages or characters are as well-known as these, but they all come to us in fully realised settings, very much a Roberts strongpoint. But the main weight in these poems is given to some moving testaments to long friendships over long distances, and to personal poems about aging, marriage and the erosion of hearing that claim immediate universality. “To Ian Stevens in Heaven” is an elegy for an old teacher with surprising gifts and great presence:

Never in possession of your timetable:

'If they line up outside I bring them in to teach'

(your George Medal lesson was well-aired).

The piece is laced with telling detail and deep feeling, strengths we find also in “Night Closure”:

I'm up and down the M62 these days,

to visit mother biding her decline

in a residential home in Huddersfield.

She meets her daily humilations

with inattention, while I turn inside out

for family news to try to pass the time.

The second half of this poem concerns the drive home, deepening into ‘warnings’ in road-signs and finally ‘notice of a night closure’. The counterpoint of this natural style with Ty Dove’s anecdotes has been a staple of at least the last three books by Tony Roberts, and what distinguishes all of them is this sense of knowledge and information worn lightly. I wouldn’t want to be without any of it.

Feb 1 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Tony Roberts

John Forth appreciates the sense of knowledge and information worn lightly that runs through the poetry of Tony Roberts

Someone said once that we must distinguish between those who collect records and those who play them. Although I’d come across a few people who do both, I knew that an important distinction was being made and that it referred to more than music. Tony Roberts plays records and dreams of playing on them, and the dream washes over all he writes. In fact I’d been trying to keep up with mid-twentieth century jazz history with the small batches of poems at the end of his last two collections, six poems in all, but now I see he was being flexible with the chronology of the period if not with its stellar names. He was doing the same with his thorough knowledge of Shakespeare – because the guy at the centre of all this is Ty ‘Prince’ Dove, a fictional Hamlet-obsessed wannabe tenor saxman who’s bouncing off real legends from the period and who could boast a childhood to rival that of the Prince himself:

the poem going on to tell of his uncle’s marrying his mother ‘in unseemly haste’ while the Prince (plain ‘Ty Dove’ then):

...stands for centuries beside the shabby juke box in their shady bar playing with the music for loose change. [“After Locking Horns with Dexter”].What really works for Roberts is the adoption of a lingo we associate with the period sustained in 4 and 5-beat lines that might be Chandler if it wasn’t jazz. I’m completely taken-in by the subterfuge. The original ‘Noir Américain’ translates as ‘American Black’, so Ty is black and also slightly ‘noir’ in the shadowy black & white sense – since ‘color’s just another fucked up way / of seeing things’ (“Prologue: Le Noir Américain”). Roberts grabs the best of all worlds when he translates his title from the French of a black woman in “The Other Side of Midnight” into American English as ‘black american’. However it’s translated, it’s good to see the original six poems take centre stage along with a few more to form “The Noir American”.

And it really does seem that this particular devil’s music has the best lines, because Roberts borrows a lot of them. The joke about a drummer asking ‘Pres’ (Lester Young) when they last played together and getting the answer ‘Tonight’; Bird telling Ty during the latter’s overblown debut ‘don’t just do something, my man, stand there’ and then going on to offer a tough aesthetic: ‘Hey, don’t you know that it’s respect that kills? / Be bold; be resolute – and don’t play me’ (“How He Jams with Bird and Hits the Water Running”). When ‘Dex’ (-ter Gordon) dreams of exile it’s because we’ve already been told that ‘Paris is Disneyland’ with quips and gags that serve to set a tone and keep it: ‘Go mingle with the Gallic epicures / advises Dexter.’ (“After Locking Horns with Dexter”). Ty himself has more than a few good lines too: when he tells a waitress who dreams of singing like Sarah Vaughan that ‘in their world/ the only way to wind up with a million / is to start with two.’ (“In which he Arrives in the Big Apple & Meets his Lady over Coffee”) – or when he addresses a noisy naval crew in a bar with a Mingus jibe: ‘Ladies, mariners, gentlemen, it’s come /to our attention you’re not getting / what you paid for, and we sure as shit / ain’t getting your attention…’ (“An Audience with the Prince”). This episode shows him running out of puff for the American scene and readying himself for a return to Paris whence he came: ‘But don’t go telling him the Big Bad Wolf / ain’t out there, because the Prince has seen its tracks’, one of several references to the drug scene. It feeds nicely into Ty’s fantasy of harnessing his own talent to that of Bill Evans who is ‘almost too cerebral’ (“Of Howling at the Moon & Digging Bill Evans”). The whole story is a chaotic bone-shaking vehicle of fact and fiction in which real characters fade in and out of recognition as it runs on its own momentum.

So, suddenly, we’re back in Paris with ‘this clued-up chick’ called Sabine who springs him from an institution where he’s being shrunk and confined for displaying too much wildness. She has an uproarious dream in which the joint fills up with famous thinkers who end up starting a bar-brawl, but at least here ‘he’s treated like an artist/ not a horn-blower’. He seems to be tasting happiness and ends by telling her she’s become his muse, but she’s having none of it: ‘Muse, my ace, she says’ (“Which Treats of Sabine’s Dream of Camus with the Prince Playing Along”). Then he’s back at Birdland, truly picaresque now, in a crisis (“He’s Hamleting”) – needing to catch up on what’s been going on while he’s been gone – and we’re becoming more aware of the problem of exile without being sure in which place he feels it the most (“On Being Back at Birdland”). There’s a moving tribute to Billie Holiday which almost breaks stride with the other poems, being a stream-(of death)-consciousness with Pres dying the same year: ‘She must have played / a thousand joints that wouldn’t let her in / except as hired help’ (“Where He Sings the Blues for Lady Day”). By the final poem he has become ‘an internal exile’ like the rest of them and in this sense the poem surely reaches beyond its own nutshell:

The English call it barking mad, this urge to put oneself through shit, time and again. Yet what can he – most sleek and quarrelsome – do other than cement his reputation as The Prince of Cats. [“Enter as Prince”]There are now thirteen long(ish) poems evolved from the original six, and at 35 pages it’s half the book. Great fun, supported by moments of great seriousness, and probably yielding more to jazz experts than I’m mustering here. Shakespeare (and not just Hamlet) references surface casually all the time and the pot-pourri certainly persuades me. I imagine it will work for them too.

The second half of the book is sub-titled ‘other lyrics’ and here we find Roberts’ familiar mix of historical and artistic contexts that are always rendered ‘personal’ in the truest sense. The poems are not afraid to be complex but always glad to keep things simple – there’s a long and cheering monologue from RLS admiring Sargent’s portrait of the family (“At Skerryvore”) and, in “Theatre”, a moment frozen from the end of The Seagull:

Not all of the personages or characters are as well-known as these, but they all come to us in fully realised settings, very much a Roberts strongpoint. But the main weight in these poems is given to some moving testaments to long friendships over long distances, and to personal poems about aging, marriage and the erosion of hearing that claim immediate universality. “To Ian Stevens in Heaven” is an elegy for an old teacher with surprising gifts and great presence:

The piece is laced with telling detail and deep feeling, strengths we find also in “Night Closure”:

The second half of this poem concerns the drive home, deepening into ‘warnings’ in road-signs and finally ‘notice of a night closure’. The counterpoint of this natural style with Ty Dove’s anecdotes has been a staple of at least the last three books by Tony Roberts, and what distinguishes all of them is this sense of knowledge and information worn lightly. I wouldn’t want to be without any of it.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2019 0 • Tags: books, John Forth, poetry