A first collection by Suzannah Evans deals with future technologies but Mat Riches is pleased to see that it is also equally concerned with human themes

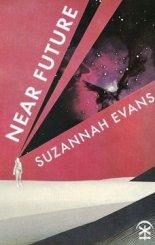

Near Future

Suzannah Evans

Nine Arches Press, 2018

ISBN 9781911027461

£9.99

Near Future

Suzannah Evans

Nine Arches Press, 2018

ISBN 9781911027461

£9.99

The blurb on the back of Near Future calls this collection “distinctive doom-pop poetry with an apocalyptic edge, a darkly humorous journey through sci-fi lullabies and northern mysteries. This is a future simulation stripped of the space-age gloss of progression.” (The mention of ‘sci-fi lullabies’ leads one to assume that the writer of the blurb is a fan of Suede B-sides. And why not? They are often amazing.)

It’s also wonderfully co-incidental that this book has come out in the year we finally see a female Doctor Who—and a female Doctor from Suzannah Evans’ home town of Sheffield, no less—as this is a book riddled with time travel.

Near Future acts as a kind of antithesis to the Jetson-like vision of the future we used to be presented with – namely one where we are cared for by kindly robots. As our technological capabilities have increased, such predictions have become more complicated and dystopian: the little things that were sent to improve our lives are turning against us. For instance, the book gives that bane of all things, the Windows Office assistant, Clippy, a far more macabre update in “The Handover”.

Half-way through the presentation

the paperclip machine tells Jamie from marketing

that the carbon atoms of his body

would be more effectively arranged as paperclips.

It’s a version of what we’ve all been thinking anyway.

If the world is to be re-configured

as paperclips, Clippy 3000 continues

then we are doing it wrong.

It requests an optimal killing package

and a carbon-harvesting system.

Another example is a technological update on Paul McCartney’s tribute to the women of the civil rights movement in “Roboblackbird” with his ‘…song downloadable / in thirteen variations’ and where ‘sometimes we hear him through our dreams / re-setting in the dead of night’. The punctuation deliberately missing from this poem suggests that it will never end and that this movement can’t be stopped.

For all the focus on what technology does to us – and to other species and the world around us – Near Future is a book about very human themes: love, life, interaction, questioning our place in the world and death. “A Contingency Plan” asks ‘What if we’re apart when the asteroid comes / or the magnetic-storm that shuts off the power?’ The collection is more about the relationships we all have, with the focus on the ‘what if we’re apart’ and less on the asteroid or magnetic-storm. While the modern contraptions and inventions keep our couple going – with a ‘nylon carpet’ to sleep on, the sustenance of a ‘vending machine’ and a ‘picnic of high-end tins’ – when events come to the crunch, it’s the first major man-made “invention” that’s important, as our protagonists manage to reunite after being separated and

...I can lie in your arms on a rooftop

our dirty faces lit by fires

Themes of the elemental and the natural, reclaiming the world and bringing us back to our senses, are woven throughout the collection. They reach a logical conclusion in “The New Tenants”, when Nature brings its own brand of chaos to our order.

When we go the ivy will slam a fist

through the double glazing, push its fingers

in between the bricks. It will sling ropes

around our walls and pull them down

like the landlord always feared…

And we see this again later in the collection in ‘Re-wilding’ as

Shrubs wriggled off their trellises

the mis-mis-shapes topiary chimed with nestlings.

Birches thickened unchecked around the pond

until beavers moved in

to begin maintenance and a family.

Humans remain present in this version of the future, but a more chastened and considerate version that takes ‘…only what we needed from the herd / making each kill last a fortnight.’

Death and loss loom throughout the book, from the potential catastrophic death of the species/planet at the start, to the death of industry, or extinct scents and finally, the realisation that even in other universes there’s no stopping death. In the galactic ‘Sliding Doors’ situation of ‘We just passed on the street’, the imagined future is still not enough to stop the very real situation of a dying father

watching forever end, as we understand it, for him

in his thin body under these thin sheets

and each seeing is bearable but a whole day

is excruciating

and, although in a parallel universe

none of this is happening

we are here in this airless room

that open window doing nothing.

The collection ends with another kind of loss, or at least a change: language as we now know it loses recognisable patterns, in “The Last Poet-in-Residence” – a terrifying thought for some. We hear about the ‘burntree’, ‘songits, ghuzzles’ and the awful most modern fear of ‘No applecharge or anything, just pen’. The eliding together of words and the dropping of conjunctions make for an interesting future where we eat our way through the ‘evergrowing potates!’ under a ‘sky always dayending / redder norange’. This is a world that seems so far away and yet is with us all the time in other countries that have internet-censorship and offer up facades of perfection to control the news, as we see in “The Censored City”

The municipal workers paint the dead grass

back to its original colour each night.

The mouths of rush-hour pedestrians

are stopped with facemarks.

Internet searches for painted grass

or municipal workers turn up nothing.

Even though we’re led to think about the future, we look through the lens of past and the present. For example, we spend a lot of time looking back at the industrial past of Sheffield in “The Taste”, where the tang of Sheffield steel is no longer felt in the mouths of everyone, or the encroaching of “Coastal Erosion”, where ‘…the sea/ /has taken bites of the land…’

Everything comes back to our impact on the world around us, and never is this clearer than in “The Human and the Starlings”. This poem reverses the roles of humanity and avian to strong effect, to make the point land…

The humans ingest prosaic through the bodies of worms

scavenged at water treatment works.

The starlings take selfies. The humans imitate

the ringing of telephones and the meowing of cats.

…

Murmurations of humans are much rarer

than they used to be, particularly in built-built-up areas.

…

The starlings have reported a drop in libido.

It’s mating season but the humans are not in the mood.

I find it interesting that the poet has chosen to include just one poem from her debut pamphlet, Confusion Species, when so many of them would have slotted into this collection very well, maybe even taking on new meanings – for example “Leeds International Swimming Pool”. Nevertheless, there are throwbacks and echoes to be had: Near Future has “Underground in the new Meanwood” while Confusion Species had “The Horses of Meanwood”; and in many ways the new collection picks up where the pamphlet left off. Confusion Species ends with a Rapture and the Near Future starts with the potential end of the world.

With six years between pamphlet and full collection, it’s clear that Suzannah Evans hasn’t rushed at this and the collection is all the better for this patience. I’m torn between wanting a new collection quickly and wanting her to take her time crafting a follow-up. Let’s hope the word doesn’t collapse in the meantime.

Dec 15 2018

London Grip Poetry Review – Suzannah Evans

A first collection by Suzannah Evans deals with future technologies but Mat Riches is pleased to see that it is also equally concerned with human themes

The blurb on the back of Near Future calls this collection “distinctive doom-pop poetry with an apocalyptic edge, a darkly humorous journey through sci-fi lullabies and northern mysteries. This is a future simulation stripped of the space-age gloss of progression.” (The mention of ‘sci-fi lullabies’ leads one to assume that the writer of the blurb is a fan of Suede B-sides. And why not? They are often amazing.)

It’s also wonderfully co-incidental that this book has come out in the year we finally see a female Doctor Who—and a female Doctor from Suzannah Evans’ home town of Sheffield, no less—as this is a book riddled with time travel.

Near Future acts as a kind of antithesis to the Jetson-like vision of the future we used to be presented with – namely one where we are cared for by kindly robots. As our technological capabilities have increased, such predictions have become more complicated and dystopian: the little things that were sent to improve our lives are turning against us. For instance, the book gives that bane of all things, the Windows Office assistant, Clippy, a far more macabre update in “The Handover”.

Another example is a technological update on Paul McCartney’s tribute to the women of the civil rights movement in “Roboblackbird” with his ‘…song downloadable / in thirteen variations’ and where ‘sometimes we hear him through our dreams / re-setting in the dead of night’. The punctuation deliberately missing from this poem suggests that it will never end and that this movement can’t be stopped.

For all the focus on what technology does to us – and to other species and the world around us – Near Future is a book about very human themes: love, life, interaction, questioning our place in the world and death. “A Contingency Plan” asks ‘What if we’re apart when the asteroid comes / or the magnetic-storm that shuts off the power?’ The collection is more about the relationships we all have, with the focus on the ‘what if we’re apart’ and less on the asteroid or magnetic-storm. While the modern contraptions and inventions keep our couple going – with a ‘nylon carpet’ to sleep on, the sustenance of a ‘vending machine’ and a ‘picnic of high-end tins’ – when events come to the crunch, it’s the first major man-made “invention” that’s important, as our protagonists manage to reunite after being separated and

Themes of the elemental and the natural, reclaiming the world and bringing us back to our senses, are woven throughout the collection. They reach a logical conclusion in “The New Tenants”, when Nature brings its own brand of chaos to our order.

And we see this again later in the collection in ‘Re-wilding’ as

Humans remain present in this version of the future, but a more chastened and considerate version that takes ‘…only what we needed from the herd / making each kill last a fortnight.’

Death and loss loom throughout the book, from the potential catastrophic death of the species/planet at the start, to the death of industry, or extinct scents and finally, the realisation that even in other universes there’s no stopping death. In the galactic ‘Sliding Doors’ situation of ‘We just passed on the street’, the imagined future is still not enough to stop the very real situation of a dying father

The collection ends with another kind of loss, or at least a change: language as we now know it loses recognisable patterns, in “The Last Poet-in-Residence” – a terrifying thought for some. We hear about the ‘burntree’, ‘songits, ghuzzles’ and the awful most modern fear of ‘No applecharge or anything, just pen’. The eliding together of words and the dropping of conjunctions make for an interesting future where we eat our way through the ‘evergrowing potates!’ under a ‘sky always dayending / redder norange’. This is a world that seems so far away and yet is with us all the time in other countries that have internet-censorship and offer up facades of perfection to control the news, as we see in “The Censored City”

Even though we’re led to think about the future, we look through the lens of past and the present. For example, we spend a lot of time looking back at the industrial past of Sheffield in “The Taste”, where the tang of Sheffield steel is no longer felt in the mouths of everyone, or the encroaching of “Coastal Erosion”, where ‘…the sea/ /has taken bites of the land…’

Everything comes back to our impact on the world around us, and never is this clearer than in “The Human and the Starlings”. This poem reverses the roles of humanity and avian to strong effect, to make the point land…

I find it interesting that the poet has chosen to include just one poem from her debut pamphlet, Confusion Species, when so many of them would have slotted into this collection very well, maybe even taking on new meanings – for example “Leeds International Swimming Pool”. Nevertheless, there are throwbacks and echoes to be had: Near Future has “Underground in the new Meanwood” while Confusion Species had “The Horses of Meanwood”; and in many ways the new collection picks up where the pamphlet left off. Confusion Species ends with a Rapture and the Near Future starts with the potential end of the world.

With six years between pamphlet and full collection, it’s clear that Suzannah Evans hasn’t rushed at this and the collection is all the better for this patience. I’m torn between wanting a new collection quickly and wanting her to take her time crafting a follow-up. Let’s hope the word doesn’t collapse in the meantime.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2018 1 • Tags: books, Mat Riches, poetry