Alex Josephy discusses a passionate and thought-provoking collection from Lynne Wycherley

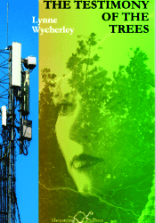

The Testimony of the Trees

Lynne Wycherley

Shoestring Press 2018

ISBN: 978-1-912524-19-8

58pp £7.50

The Testimony of the Trees

Lynne Wycherley

Shoestring Press 2018

ISBN: 978-1-912524-19-8

58pp £7.50

‘How is the notion of the self-conscious Anthropocene altered when human beings refuse to recognize the planetary consequences of their actions?’ Jean-Thomas Tremblay in Los Angeles Review of Books June 2018

In this small collection, Lynne Wycherley makes an essential contribution to eco-poetry, extending its power to move and inspire readers. The poems call out to us to recognise the planetary consequences of everyday choices. They combine to form an eloquent plea that seems to come from the heart of the natural world, testimony transcribed by a poet able to tune into the smallest, most vital signals that all is not well on our planet. From the outset, the sequence demands close attention and dares the reader to take responsibility for all that is in danger.

Wycherley’s voice is intriguing; in brief lines and fractured references, she composes a unique field of imagery, in which the natural world interacts with threats posed by the digital age. For instance, in ‘As if a Gale’ she depicts the effects of microwaves on trees:

... frail, in the ever-wind,

stems, serifs, pared back,

laterals lost to sky-wolves

as if a gale has shorn us from one side…

To understand these poems, you need to tangle with the language of natural forms at the same time as that of new technologies, and with Wycherley’s agile manipulation of terms and assumptions. Never less than entirely serious, the poems are also entrancingly playful. Like the hare she admires, the poet makes her points in quick leaps and bounds, as in these lines from ‘A Prayer across Time’:

a train: the shell-of-a-train

a phone: the shell-of-a-phone.

Box in box, estrangement squared

the apple’s scented integer mislaid

calling at : 4G, 5G

smoked-out cities

Phones are kept in shell-like covers; phones, trains and everything else become hollow shells in virtual reality, boxes in game-boxes; apples in the world of Apple are insubstantial shadows of apples. Cities are ‘smoked-out’ by pollution, maybe also smoked-out, emptied out, in the way that bees might be smoked out of a tree.

In other poems the technology is portrayed as a kind of perverted life-form, openly hostile toward ‘nature’. Masts ‘spike the sky’; routers and boosters are ‘leeched to walls’.

Trees themselves, their beauty and their connotations, add a supple strength to the argument. In ‘Firstborn’ they appear as elders – ‘White-haired in moonlight’. In ‘The Eyes of a Fox’ the scent of a cedar is ‘A five-fathom shiver, quench/of deep green’. They appear as heroic figures in a mythic battle for survival:

No sea-mark in data storms.

A birch in sail: moon-rigged,

a chestnut: brigantine.

As can be seen in these lines, the collection focuses particularly on the effects of ‘radiofrequency’ radiation from mobile-phone masts and other electronic devices; Wycherley identifies these as an invisible but deadly encroachment, and the poems speak with great urgency of dangers we all face. Referring to genome damage, half-rhyming that with environmentalists’ demand for radiation-free ‘white zones’, she invokes the DNA spiral in the same breath as Dante’s golden ladder:

micro-wands, antennas.

No ‘white zone’: will a genome

furl its ladder

leave love midair

Dante’s light receding

in pale rungs?

Ironically, I found myself resorting to extensive internet searches to make sure I understood the technical references which are everywhere in the poems. If you are about to read this book, it’s helpful to note that in-between the two sections there are very helpful ‘Notes on the Sequence’; entirely my own fault, but I wish I had looked ahead and found these pages the first time I read through. Does the need for footnotes and quite a lot of researching of unfamiliar references make a collection less effective? In my opinion it shouldn’t; as readers of poetry, we are always exploring new corners of the spoken and written world. It’s our obligation to check on anything we don’t comprehend. These poems are challenging in that way; they make demands on a reader’s curiosity. There is biological language too, and other references that reminded me of Robert Macfarlane’s lament for the ‘lost words’ of the Oxford Junior Dictionary: ‘the slow wonder/of a primrose’; Wycherley’s direct rage against the impoverishment of language:

Not a child but an end-user.

Not a carer but a high-speed interface.

Not eyes but an emoticon.

The first, longer sequence also conveys an increasing sense of validity through the epigraphs that precede each poem. Wycherley draws on an array of authorities: scientists, philosophers, doctors, poets. Gandhi puts in an appearance, as do Jung, Blake, Shakespeare, and as a presiding spirit, I imagine, Rachel Carson.

The book also contains a ‘Coda’, a second sequence of poems that celebrate nature in slightly wider contexts, though still with dark undercurrents. There are moments of ecstatic longing, as in ‘Poacher’s Child’ where a daughter remembers her father, and delicate, precise evocations of a fox and a Buckfast Abbey bee-keeper. I loved the Chagall reference in the love poem, ‘On Midsummer Hill’:

The sun drifts down

like an angel from Chagall,

our world still burning in its arms.

Wycherley’s passionate belief in the benign influence of nature and the need to turn back the advance of ‘virtual’ living energises every poem. I’ve enjoyed this collection more with each re-reading, and can’t wait to discuss it with others interested in the genre.

Nov 19 2018

London Grip Poetry Review – Lynne Wycherley

Alex Josephy discusses a passionate and thought-provoking collection from Lynne Wycherley

‘How is the notion of the self-conscious Anthropocene altered when human beings refuse to recognize the planetary consequences of their actions?’ Jean-Thomas Tremblay in Los Angeles Review of Books June 2018

In this small collection, Lynne Wycherley makes an essential contribution to eco-poetry, extending its power to move and inspire readers. The poems call out to us to recognise the planetary consequences of everyday choices. They combine to form an eloquent plea that seems to come from the heart of the natural world, testimony transcribed by a poet able to tune into the smallest, most vital signals that all is not well on our planet. From the outset, the sequence demands close attention and dares the reader to take responsibility for all that is in danger.

Wycherley’s voice is intriguing; in brief lines and fractured references, she composes a unique field of imagery, in which the natural world interacts with threats posed by the digital age. For instance, in ‘As if a Gale’ she depicts the effects of microwaves on trees:

To understand these poems, you need to tangle with the language of natural forms at the same time as that of new technologies, and with Wycherley’s agile manipulation of terms and assumptions. Never less than entirely serious, the poems are also entrancingly playful. Like the hare she admires, the poet makes her points in quick leaps and bounds, as in these lines from ‘A Prayer across Time’:

Phones are kept in shell-like covers; phones, trains and everything else become hollow shells in virtual reality, boxes in game-boxes; apples in the world of Apple are insubstantial shadows of apples. Cities are ‘smoked-out’ by pollution, maybe also smoked-out, emptied out, in the way that bees might be smoked out of a tree.

In other poems the technology is portrayed as a kind of perverted life-form, openly hostile toward ‘nature’. Masts ‘spike the sky’; routers and boosters are ‘leeched to walls’.

Trees themselves, their beauty and their connotations, add a supple strength to the argument. In ‘Firstborn’ they appear as elders – ‘White-haired in moonlight’. In ‘The Eyes of a Fox’ the scent of a cedar is ‘A five-fathom shiver, quench/of deep green’. They appear as heroic figures in a mythic battle for survival:

As can be seen in these lines, the collection focuses particularly on the effects of ‘radiofrequency’ radiation from mobile-phone masts and other electronic devices; Wycherley identifies these as an invisible but deadly encroachment, and the poems speak with great urgency of dangers we all face. Referring to genome damage, half-rhyming that with environmentalists’ demand for radiation-free ‘white zones’, she invokes the DNA spiral in the same breath as Dante’s golden ladder:

Ironically, I found myself resorting to extensive internet searches to make sure I understood the technical references which are everywhere in the poems. If you are about to read this book, it’s helpful to note that in-between the two sections there are very helpful ‘Notes on the Sequence’; entirely my own fault, but I wish I had looked ahead and found these pages the first time I read through. Does the need for footnotes and quite a lot of researching of unfamiliar references make a collection less effective? In my opinion it shouldn’t; as readers of poetry, we are always exploring new corners of the spoken and written world. It’s our obligation to check on anything we don’t comprehend. These poems are challenging in that way; they make demands on a reader’s curiosity. There is biological language too, and other references that reminded me of Robert Macfarlane’s lament for the ‘lost words’ of the Oxford Junior Dictionary: ‘the slow wonder/of a primrose’; Wycherley’s direct rage against the impoverishment of language:

The first, longer sequence also conveys an increasing sense of validity through the epigraphs that precede each poem. Wycherley draws on an array of authorities: scientists, philosophers, doctors, poets. Gandhi puts in an appearance, as do Jung, Blake, Shakespeare, and as a presiding spirit, I imagine, Rachel Carson.

The book also contains a ‘Coda’, a second sequence of poems that celebrate nature in slightly wider contexts, though still with dark undercurrents. There are moments of ecstatic longing, as in ‘Poacher’s Child’ where a daughter remembers her father, and delicate, precise evocations of a fox and a Buckfast Abbey bee-keeper. I loved the Chagall reference in the love poem, ‘On Midsummer Hill’:

Wycherley’s passionate belief in the benign influence of nature and the need to turn back the advance of ‘virtual’ living energises every poem. I’ve enjoyed this collection more with each re-reading, and can’t wait to discuss it with others interested in the genre.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, ecology, poetry reviews, year 2018 0 • Tags: Alex Josephy, books, ecology, poetry