Angela Topping admires Mark Mansfield’s carefully controlled and crafted poems for their plain speaking

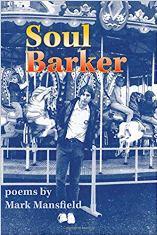

Soul Barker

Mark Mansfield

Creative Space

ISBN 978-1981259021

76pp $12

Soul Barker

Mark Mansfield

Creative Space

ISBN 978-1981259021

76pp $12

Mansfield is an American poet, whose work has been widely published on both sides of the pond. Soul Barker is his second collection. Interestingly, he is deeply versed in the English tradition, and references poets like Thomas Wyatt, William Blake and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, in some of his poems – for example, in the sad and sensual ‘How Like You This?’, where he remembers lost loves of his own:

I hear their voices clear as if

the years like fallen leaves

had flown back to their greenest hour –

when kismet’s loom unweaves:

each smiles, then disappears, as she

who I know is no more

keeps our rendezvous I failed

and waits – just as before.

This poem strongly recalls ‘They Flee from Me’ but acts as a response to it. Whereas Anne Boleyn had left Wyatt, here the poet’s lost loves come back to him in dreams. Wyatt has to watch his former lover from a distance, grown strange, but Mansfield’s ghosts are familiar and seek him out. I love the idea of the leaves going back in time to ‘their greenest hour’, because it reminds me of Frost’s ‘Nothing Gold Can Stay’. (‘Her early leaf’s a flower;/ but only so an hour.’). There is something dark about this poem, however, as the sardonically ominous allusion in the poem’s title to a pivotal passage from ‘They Flee from Me’ suggests. It is as if the poem’s speaker is saying how like you this? – this fatefully recurrent dream I have wrought by not keeping my promise? The reader gets the feeling that the ghosts are not necessarily well disposed towards the person who failed to make the rendezvous. There is a poem by the War Poet, Alan Seeger called ‘I Have a Rendezvous with Death’, a date that cannot be evaded, which is referenced here, to imply these ghosts will take the speaker to his grave. And of course, Wyatt survived Boleyn and must have watched her go to her execution, beyond his love and help. He was even ‘interviewed’ by her accusers, but released, as it was proved his alliance with her was before she knew Henry VIII. For a poem of only twelve lines, there is a lot packed in here, yet it appears effortless.

There is a strong elegiac movement of tone, throughout this collection. Mansfield takes the reader to haunted bars, unravelling people’s tragedies, as in ‘Boog’s Blues’, where he recounts the story of an older boy who used to busk on the boardwalk, admired by the younger ones, like the speaker of the poem:

I was one of those gypsy kids

who followed Boogie’s harp.

Piping the dawn awake, he’d laugh,

Bojangling down the wharf

until one day he disappeared:

drafted, then killed in the War.

The first stanza and the last stanza of this poem are the same but mean different things. By the time the ending comes, the ‘stranger’ who ‘struts the boards’ is Boog’s ghost, returning to the place he was happy, and still playing his ghostly harp. Another lost place is ‘Blu’s’, a club down on the shore, beyond the boardwalk, closed and then burned down. The tragedy there was the owner’s girlfriend, drowned in a boating accident: ‘her cut-rate fate/ speedballs marinated in ludes and booze’. She is represented in the poem by a nude painting of her which hung behind the bar. The day after she died, Blu and the painting disappeared. The story is told backwards in the poem; there is a sense of recollection, a story that has forced its way out of memory. In ‘Franklin Square’ Mansfield adds to the theme of music by employing the old song George Formby used to sing, ‘Leaning on a Lamppost’, originally written by Noel Gay. But he twists the narrative, something he often does in these poems, to have a girl waiting for the speaker, humming ‘that song’ while leaning on a lamppost, but at night, instead of daytime, vanishing after whispering to the speaker:

Then, bending near, whispered – but as to what

she said, I couldn’t make out a word. A strong

gust suddenly arose, and as it did, she turned,

vanishing in the snow before she reached the curb.

Chilling, yes, and one only notices afterwards, this poem is also a brilliantly balanced sonnet.

There are also elegies for lost relationships, like the scene in a motel – one of those lonely overnight drive-in hotels in America which punctuate empty miles, so a traveller can rest from driving before continuing on their way. ‘Blue Motel’ is a mere eight lines of a tightly-knit lyric, but its poignancy is in the ‘one pillow’, the dust motes ‘dancing’ and the sound of a song ‘she’ liked on the radio. It’s a study of loneliness. ‘My Lost Saints’ recalls both Thom Gunn’s ‘My Sad Captains’, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnet 43, in which she mentions ‘my lost saints’, martyrs she venerated as a child. It remembers a bar called The SIDE SHOW, and the friends he knew there, one whom he married but it didn’t work out, a boy named Jack Fox who ‘is no more’, and the poet himself ‘a boy… near a Star on the Walk of Fame than never was’. Everyone can identify with this scenario: a place we used to go, the friends we met there. It’s the theme of lost content, in which our old friends become our ‘lost saints.’

Lest this collection appears to be all sorrow and loss, there is a darkly witty vampire poem, ‘VLAD’S’ that’s chocka with literary jokes: ‘Each song’s the mirrored image of the next/ or the one before. So here I am again/ at least four sets tonight, vamping around’. Mansfield manages to sustain this throughout, and the last dance is a ladies’ choice, which hints how attractive Dracula is. This bar is much more glamorous than the human bars in the book, which all appear tawdry or closed down and firmly in the past.

The theme of horror is not restricted to vampires. ‘A Stopped Watch’ takes its title from a Ray Bradbury short story, and another poem. ‘To Helena’ references Poe’s ‘To Helen’. In the former, Mansfield shares a story fit to strike horror into the hearts of readers, and foreshadows the Trump era. It concerns the assassination of Kennedy. The poet as a young boy, is at junior high in Alabama, because his father’s postings in the army mean moving around. He’s known as ‘Yankee’ not by his name. When the teacher comes in with the news, there is at first stunned silence, then, unlike the outcry of sorrow which most people felt, there is an outbreak of celebration, cheering, clapping, jumping for joy. Mansfield builds up carefully to the killer last line, by clutching Bradbury’s book, Something Wicked This Way Comes two stanzas before the boy in the next desk winks and speaks to him: ‘Thank Gawd/ that nigga-loving Catholic’s dead.’ The Alabama of To Kill a Mockingbird has not improved one iota.

Mansfield’s social conscience also reveals itself in the opening poem, ‘The Drowning Boat’ which speaks to me of babies, born and unborn, who die needlessly trying to escape war and drought. The poem’s epigraph comes from Louis MacNeice’s ‘Prayer Before Birth’, a dramatic monologue in the form of a prayer spoken by an unborn infant intuiting the horrors of humankind’s inhumanity that await. Mansfield’s poem, however, is narrated by one ‘whose small/charmed’ life – favoured by fortune and not victim to ‘the blast/sites of chance’ – stands out ‘in high relief’ from those of the world’s refugees, destined to be lost ‘aboard a drowning boat … as the water surged at last’. Where MacNeice’s unborn speaker sends the world an agonizing prayer, ‘The Drowning Boat’ concludes with the death rattle from an infant’s ‘day-old lungs’ aboard a doomed boat being likened to ‘the crack of doom/which no one heard’ announcing a ‘ghostly’ eschatological presence – that like MacNeice’s speaker is ‘not yet born’. Poets have a duty to speak up about such things, and Mansfield is able to do this subtly and without climbing on a soap-box, but inviting the reader in with his imagery and form.

The interest in form is much in evidence. These poems are carefully controlled and crafted, the metre sure-footed and the rhymes skilful and subtle. There is a smattering of typographical experimentation, always to the purpose. The form never distracts, however. There are many more poems I leave for the reader to discover. This is a collection which repays re-reading many times. The themes of music, horror, lost content and passing of time, haunting and humanity, are big ones, but so deftly handled. These poems do what poems should: they speak to the reader in the silence of their minds, and echo there.

Oct 8 2018

London Grip Poetry Review – Mark Mansfield

Angela Topping admires Mark Mansfield’s carefully controlled and crafted poems for their plain speaking

Mansfield is an American poet, whose work has been widely published on both sides of the pond. Soul Barker is his second collection. Interestingly, he is deeply versed in the English tradition, and references poets like Thomas Wyatt, William Blake and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, in some of his poems – for example, in the sad and sensual ‘How Like You This?’, where he remembers lost loves of his own:

This poem strongly recalls ‘They Flee from Me’ but acts as a response to it. Whereas Anne Boleyn had left Wyatt, here the poet’s lost loves come back to him in dreams. Wyatt has to watch his former lover from a distance, grown strange, but Mansfield’s ghosts are familiar and seek him out. I love the idea of the leaves going back in time to ‘their greenest hour’, because it reminds me of Frost’s ‘Nothing Gold Can Stay’. (‘Her early leaf’s a flower;/ but only so an hour.’). There is something dark about this poem, however, as the sardonically ominous allusion in the poem’s title to a pivotal passage from ‘They Flee from Me’ suggests. It is as if the poem’s speaker is saying how like you this? – this fatefully recurrent dream I have wrought by not keeping my promise? The reader gets the feeling that the ghosts are not necessarily well disposed towards the person who failed to make the rendezvous. There is a poem by the War Poet, Alan Seeger called ‘I Have a Rendezvous with Death’, a date that cannot be evaded, which is referenced here, to imply these ghosts will take the speaker to his grave. And of course, Wyatt survived Boleyn and must have watched her go to her execution, beyond his love and help. He was even ‘interviewed’ by her accusers, but released, as it was proved his alliance with her was before she knew Henry VIII. For a poem of only twelve lines, there is a lot packed in here, yet it appears effortless.

There is a strong elegiac movement of tone, throughout this collection. Mansfield takes the reader to haunted bars, unravelling people’s tragedies, as in ‘Boog’s Blues’, where he recounts the story of an older boy who used to busk on the boardwalk, admired by the younger ones, like the speaker of the poem:

The first stanza and the last stanza of this poem are the same but mean different things. By the time the ending comes, the ‘stranger’ who ‘struts the boards’ is Boog’s ghost, returning to the place he was happy, and still playing his ghostly harp. Another lost place is ‘Blu’s’, a club down on the shore, beyond the boardwalk, closed and then burned down. The tragedy there was the owner’s girlfriend, drowned in a boating accident: ‘her cut-rate fate/ speedballs marinated in ludes and booze’. She is represented in the poem by a nude painting of her which hung behind the bar. The day after she died, Blu and the painting disappeared. The story is told backwards in the poem; there is a sense of recollection, a story that has forced its way out of memory. In ‘Franklin Square’ Mansfield adds to the theme of music by employing the old song George Formby used to sing, ‘Leaning on a Lamppost’, originally written by Noel Gay. But he twists the narrative, something he often does in these poems, to have a girl waiting for the speaker, humming ‘that song’ while leaning on a lamppost, but at night, instead of daytime, vanishing after whispering to the speaker:

Chilling, yes, and one only notices afterwards, this poem is also a brilliantly balanced sonnet.

There are also elegies for lost relationships, like the scene in a motel – one of those lonely overnight drive-in hotels in America which punctuate empty miles, so a traveller can rest from driving before continuing on their way. ‘Blue Motel’ is a mere eight lines of a tightly-knit lyric, but its poignancy is in the ‘one pillow’, the dust motes ‘dancing’ and the sound of a song ‘she’ liked on the radio. It’s a study of loneliness. ‘My Lost Saints’ recalls both Thom Gunn’s ‘My Sad Captains’, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnet 43, in which she mentions ‘my lost saints’, martyrs she venerated as a child. It remembers a bar called The SIDE SHOW, and the friends he knew there, one whom he married but it didn’t work out, a boy named Jack Fox who ‘is no more’, and the poet himself ‘a boy… near a Star on the Walk of Fame than never was’. Everyone can identify with this scenario: a place we used to go, the friends we met there. It’s the theme of lost content, in which our old friends become our ‘lost saints.’

Lest this collection appears to be all sorrow and loss, there is a darkly witty vampire poem, ‘VLAD’S’ that’s chocka with literary jokes: ‘Each song’s the mirrored image of the next/ or the one before. So here I am again/ at least four sets tonight, vamping around’. Mansfield manages to sustain this throughout, and the last dance is a ladies’ choice, which hints how attractive Dracula is. This bar is much more glamorous than the human bars in the book, which all appear tawdry or closed down and firmly in the past.

The theme of horror is not restricted to vampires. ‘A Stopped Watch’ takes its title from a Ray Bradbury short story, and another poem. ‘To Helena’ references Poe’s ‘To Helen’. In the former, Mansfield shares a story fit to strike horror into the hearts of readers, and foreshadows the Trump era. It concerns the assassination of Kennedy. The poet as a young boy, is at junior high in Alabama, because his father’s postings in the army mean moving around. He’s known as ‘Yankee’ not by his name. When the teacher comes in with the news, there is at first stunned silence, then, unlike the outcry of sorrow which most people felt, there is an outbreak of celebration, cheering, clapping, jumping for joy. Mansfield builds up carefully to the killer last line, by clutching Bradbury’s book, Something Wicked This Way Comes two stanzas before the boy in the next desk winks and speaks to him: ‘Thank Gawd/ that nigga-loving Catholic’s dead.’ The Alabama of To Kill a Mockingbird has not improved one iota.

Mansfield’s social conscience also reveals itself in the opening poem, ‘The Drowning Boat’ which speaks to me of babies, born and unborn, who die needlessly trying to escape war and drought. The poem’s epigraph comes from Louis MacNeice’s ‘Prayer Before Birth’, a dramatic monologue in the form of a prayer spoken by an unborn infant intuiting the horrors of humankind’s inhumanity that await. Mansfield’s poem, however, is narrated by one ‘whose small/charmed’ life – favoured by fortune and not victim to ‘the blast/sites of chance’ – stands out ‘in high relief’ from those of the world’s refugees, destined to be lost ‘aboard a drowning boat … as the water surged at last’. Where MacNeice’s unborn speaker sends the world an agonizing prayer, ‘The Drowning Boat’ concludes with the death rattle from an infant’s ‘day-old lungs’ aboard a doomed boat being likened to ‘the crack of doom/which no one heard’ announcing a ‘ghostly’ eschatological presence – that like MacNeice’s speaker is ‘not yet born’. Poets have a duty to speak up about such things, and Mansfield is able to do this subtly and without climbing on a soap-box, but inviting the reader in with his imagery and form.

The interest in form is much in evidence. These poems are carefully controlled and crafted, the metre sure-footed and the rhymes skilful and subtle. There is a smattering of typographical experimentation, always to the purpose. The form never distracts, however. There are many more poems I leave for the reader to discover. This is a collection which repays re-reading many times. The themes of music, horror, lost content and passing of time, haunting and humanity, are big ones, but so deftly handled. These poems do what poems should: they speak to the reader in the silence of their minds, and echo there.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2018 0 • Tags: Angela Topping, books, poetry