Its title notwithstanding, Elizabeth Parker’s new collection is far from being shambolic, observes Wendy Klein

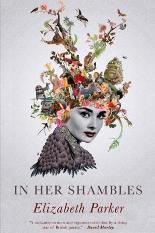

In Her Shambles

Elizabeth Parker

Seren Books

ISBN 978-1-724460

59 pp £9.99

In Her Shambles

Elizabeth Parker

Seren Books

ISBN 978-1-724460

59 pp £9.99

Of Elizabeth Parker’s debut collection, Martin Malone, former editor of The Interpreter’s House comments that, “she has a canny way with the repeated phrase and a technical control that’s impressive yet lightly worn.” Reviewing this collection for Wales Arts Review, Sophie Baggot describes it as “an ode to women’s togetherness in every sense,” but in conclusion comments that while she wasn’t “wowed” by every page, the poems dazzled enough to “emit an exceedingly warm glow.” Both reviewers have touched upon areas I would like to expand on further here.

From the opening poem (‘Crockery’), it is evident that the reader is in the hands of a highly skilled wordsmith. In only ten lines, which I guess to be about a lover’s departure, arresting images leap off the pages: “your index finger a pink glow in the saltcellar’s skirt”, “The wine glass has peeled a crescent from your mouth”, “…I watch your coffee ripple / when you knock the table with a knee.” In the second poem, ‘Clasp’, the protagonist

…scrunches onion paper

pinches a tooth of garlic from its husk.

Such a knock-out image of garlic, bracketed by good verbs, another facet of Parker’s writing. In ‘White Vase’:

She fired it

clay sintering in her kiln

until its pores shrank.

And even more striking, in ‘Rivers’:

In summer people meet at my river

their bare legs tassel its banks.

Sophie Baggot’s description of this collection as an ode to women is corroborated by Parker’s moving pieces about the fate of Lavinia as portrayed in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus. She is raped, then has her hands cut off and her tongue cut, ensuring she has no means of revealing the identity of her assailants. Parker’s version unfolds through three short poems relating the poet’s response to reading about the sorry heroine and seeing the play performed with different men at different times: ‘I. John’, ‘II. Neil’ and ‘III. Paul’, followed by an unbearably poignant 12-line piece, ‘Their Names’, which details Lavinia’s attempts to write and speak without her hands or tongue, her efforts erased as the sea ‘silenced’ the sand. The sequence is craftily interrupted by a poem simply titled ’Hands’, which does not appear to relate to Lavinia at all, apart from referencing hands. Twelve pages later, when the reader thinks that the poet has abandoned Lavinia, she reappears in ‘Lavinia Writes’. With meticulous imagery, Parker describes the process by which her subject is enabled to write her story in blood:

I dipped a finger in my mouth

strummed then picked the stitches

in the root of my stolen tongue,

I tipped my head over the paper

let my words pump, breach the dam

fill fibres glut pores

and once again, terrific choice of verbs: dipped, strummed, picked.

In further service to abused women in history, Parker revives the story of Dante Gabriel Rossetti who buried the only volume of his poems with his wife Lizzie Siddal’s body, later paying to have her body exhumed so he could edit his work and re-publish. This is possibly my favourite poem in the collection for the way in which she compares the contemporary techniques involved in word processing with the editing process undertaken by Rossetti to restore his poems:

I open blank documents

select, copy

emails, text messages

paste old words

to clean screens

He chose a new typeset

edited his metaphors

for her lips

filled wormholes

with new words for her hair

tweaked his meter

to quicken her pulse

and in closing:

I spell-check

save as

rename

print

close

shut down.

As reviewer Martin Malone comments, Elizabeth Parker makes clever use of ‘repeated phrase,’ immediately evident in the final poem of the Lavinia set where she restores Lavinia’s ability to communicate. The first line of each stanza begins with intent as the tongue-less, hand-less maiden insists on writing her story in blood:

I dipped a finger in my mouth

I tipped my head over the paper

I sign the carpet

…

I refuse ink

I sign the carpet

I refuse ink

She takes a similar approach with list poems where she uses a string of images to create characterisation. In ‘Rescues’, a touching ‘father’ poem, she uses a sequence of carefully selected images from nature which reveal the father’s skill in freeing trapped creatures: birds, a fallow doe, ‘caught in a boundary fence, fetlock trapped in the top-straining wires’, ‘barely-there weight of a pipistrelle / he scooped from the outdoor loo’, ‘House martin chicks fledging early / from the mud bowl of the nest’, and most strikingly original:

Birds, shrews, mice

pried from the white Portcullis

of the cat’s teeth.

Here each image unveils a different aspect of fathering up until the final stanza where he ‘rescues’

His three daughters

calling to him from their cities

shrill cry of the phone

his voice, still Brummie soft,

saving us each time.

There is technical control evident throughout Parker’s poems, though in some of the longer pieces, I sometimes had a sense of a device being over used. In ‘Manus’ (Latin for ‘a hand), the poet begins with a quote from the journal of anatomy proposing that “the hominid lineage’ began when chimpanzees started to throw rocks as weapons. The poem sets out as a narrative in which the poet-observer is reading the newspaper and watching her lover play the piano. Nearly three pages long, it consists of the musings of the observer alternated with anatomical quotations to do with the functioning of hand/hands, finishing with:

Your hands

conspiring to do nothing more

than quicken my pulse.

There is deftness in the way in which Parker blends the anatomy of hands with their sensuality in love-making, but the stacking of images, in my view, could have done with some editing. Indeed, a more successful ‘piano’ poem, titled ‘Piano’, is a spikey piece, terse and to-the-point, which deals with the familiar pattern in which children are offered piano lessons, but never ‘keep it up.’

Each year the piano turner arrived.

We watched him bow over the soundboard

unscrewing hammers with flattened heads.

When the pupils lose interest, the piano becomes a sort of ‘being’ in itself.

Someone lifted a loose key.

The piano stood gap-toothed.

Apt and original; we have all seen these gap-toothed pianos.

In summary In her Shambles is anything but shambolic. It has a satisfying complexity, which is rewarded by a second or third reading. Portraits, conversations, love poems and nature pieces are executed with skill and delicacy, often through a combination of repetition and a build-up of images. This works best for me when a narrative emerges. On the few occasions where it does not, my impression is of a sequence of images beautifully crafted, but somehow unrealised. Nonetheless, layered with history, legend, and stitched together with rich and original vocabulary, it is a praise-worthy debut collection.

Sep 9 2018

London Grip Poetry Review – Elizabeth Parker

Its title notwithstanding, Elizabeth Parker’s new collection is far from being shambolic, observes Wendy Klein

Of Elizabeth Parker’s debut collection, Martin Malone, former editor of The Interpreter’s House comments that, “she has a canny way with the repeated phrase and a technical control that’s impressive yet lightly worn.” Reviewing this collection for Wales Arts Review, Sophie Baggot describes it as “an ode to women’s togetherness in every sense,” but in conclusion comments that while she wasn’t “wowed” by every page, the poems dazzled enough to “emit an exceedingly warm glow.” Both reviewers have touched upon areas I would like to expand on further here.

From the opening poem (‘Crockery’), it is evident that the reader is in the hands of a highly skilled wordsmith. In only ten lines, which I guess to be about a lover’s departure, arresting images leap off the pages: “your index finger a pink glow in the saltcellar’s skirt”, “The wine glass has peeled a crescent from your mouth”, “…I watch your coffee ripple / when you knock the table with a knee.” In the second poem, ‘Clasp’, the protagonist

Such a knock-out image of garlic, bracketed by good verbs, another facet of Parker’s writing. In ‘White Vase’:

And even more striking, in ‘Rivers’:

Sophie Baggot’s description of this collection as an ode to women is corroborated by Parker’s moving pieces about the fate of Lavinia as portrayed in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus. She is raped, then has her hands cut off and her tongue cut, ensuring she has no means of revealing the identity of her assailants. Parker’s version unfolds through three short poems relating the poet’s response to reading about the sorry heroine and seeing the play performed with different men at different times: ‘I. John’, ‘II. Neil’ and ‘III. Paul’, followed by an unbearably poignant 12-line piece, ‘Their Names’, which details Lavinia’s attempts to write and speak without her hands or tongue, her efforts erased as the sea ‘silenced’ the sand. The sequence is craftily interrupted by a poem simply titled ’Hands’, which does not appear to relate to Lavinia at all, apart from referencing hands. Twelve pages later, when the reader thinks that the poet has abandoned Lavinia, she reappears in ‘Lavinia Writes’. With meticulous imagery, Parker describes the process by which her subject is enabled to write her story in blood:

and once again, terrific choice of verbs: dipped, strummed, picked.

In further service to abused women in history, Parker revives the story of Dante Gabriel Rossetti who buried the only volume of his poems with his wife Lizzie Siddal’s body, later paying to have her body exhumed so he could edit his work and re-publish. This is possibly my favourite poem in the collection for the way in which she compares the contemporary techniques involved in word processing with the editing process undertaken by Rossetti to restore his poems:

As reviewer Martin Malone comments, Elizabeth Parker makes clever use of ‘repeated phrase,’ immediately evident in the final poem of the Lavinia set where she restores Lavinia’s ability to communicate. The first line of each stanza begins with intent as the tongue-less, hand-less maiden insists on writing her story in blood:

She takes a similar approach with list poems where she uses a string of images to create characterisation. In ‘Rescues’, a touching ‘father’ poem, she uses a sequence of carefully selected images from nature which reveal the father’s skill in freeing trapped creatures: birds, a fallow doe, ‘caught in a boundary fence, fetlock trapped in the top-straining wires’, ‘barely-there weight of a pipistrelle / he scooped from the outdoor loo’, ‘House martin chicks fledging early / from the mud bowl of the nest’, and most strikingly original:

Here each image unveils a different aspect of fathering up until the final stanza where he ‘rescues’

There is technical control evident throughout Parker’s poems, though in some of the longer pieces, I sometimes had a sense of a device being over used. In ‘Manus’ (Latin for ‘a hand), the poet begins with a quote from the journal of anatomy proposing that “the hominid lineage’ began when chimpanzees started to throw rocks as weapons. The poem sets out as a narrative in which the poet-observer is reading the newspaper and watching her lover play the piano. Nearly three pages long, it consists of the musings of the observer alternated with anatomical quotations to do with the functioning of hand/hands, finishing with:

There is deftness in the way in which Parker blends the anatomy of hands with their sensuality in love-making, but the stacking of images, in my view, could have done with some editing. Indeed, a more successful ‘piano’ poem, titled ‘Piano’, is a spikey piece, terse and to-the-point, which deals with the familiar pattern in which children are offered piano lessons, but never ‘keep it up.’

When the pupils lose interest, the piano becomes a sort of ‘being’ in itself.

Apt and original; we have all seen these gap-toothed pianos.

In summary In her Shambles is anything but shambolic. It has a satisfying complexity, which is rewarded by a second or third reading. Portraits, conversations, love poems and nature pieces are executed with skill and delicacy, often through a combination of repetition and a build-up of images. This works best for me when a narrative emerges. On the few occasions where it does not, my impression is of a sequence of images beautifully crafted, but somehow unrealised. Nonetheless, layered with history, legend, and stitched together with rich and original vocabulary, it is a praise-worthy debut collection.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2018 0 • Tags: books, poetry, Wendy Klein