Camera Eye / I, Camera: Brian Docherty considers Jacqueline Saphra’s poem sequence based on remarkable photographs of and by Lee Miller

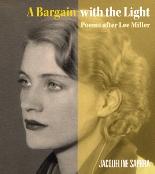

A Bargain with the Light

A Bargain with the Light

Jacqueline Saphra

(London: Hercules Editions, 2017)

ISBN 978-0-9572738-6-3.

£10.

Christopher Isherwood’s 1939 novel, Goodbye To Berlin, set in 1929, and the source for the Broadway musical, and 1972 film, Cabaret, opens with the narrator claiming

I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.

Recording the man shaving at the window opposite, and the woman in the

kimono washing her hair. Some day, all this will have to be developed,

carefully printed, fixed.

Our reactions could include ‘Voyeurism’, ‘Why is this Art’, ‘People, especially women, being objectified’, ‘What about permission, or subject involvement’, ‘The Camera never lies’. ‘Oh really’, and so on. Isherwood’s model of photography clearly owes more to say, the type of photographs taken by Henri Cartier-Bresson, than to the landscapes of Ansel Adams. We might also note that some of the records issued under the name of Miles Davis, Bitches Brew for example, owe as much to the editorial creativity of producer Teo Macero, than to Davis. (There is a well-known anecdote about Davis walking into Columbia Records office, hearing some music playing, asking ‘What’s that?‘ and being told ‘That’s your new LP, Mr Davis.’) And that’s before we get to relatively simple techniques such as cropping, framing, tinting, re-touching and focussing.

Given that most early photographers were men, Julia Margaret Cameron being a notable exception, there is an immediate issue here, addressed by Laura Mulvey, bell hooks, Lorraine Gamman and others; see for example the British Journal of Photography BJP 7859: Female Gaze. Jacqueline Saphra’s book, the latest in Hercules Press’ exemplary series of publications, addresses some of these concerns in the introductory essay, ‘Lee Miller: Seer and Seen’ by Patricia Allmer, and in Saphra’s Introduction to the poems.

First, a note on the poems themselves, a sequence of 15 sonnets, a crown or corona of sonnets. This is in itself a notable achievement; those of us who write occasional sonnets, and struggle with the form, still the Gold Standard of English verse, can only applaud Saphra’s craft skills. As readers will know, this involves writing, in whatever order, 14 sonnets, then making the 15th sonnets from existing lines from the other 14.

Each of these sonnets is an ekphrastic response to a photograph either by Lee Miller, or of Lee Miller. Six images from Miller’s archives, two of Miller by David Scherman, one self-portrait, one nude portrait by Man Ray, one Miller family group by an unknown photographer, one of Miller and her mother, and two nudes taken by her father Theodore Miller. One of these is of Miller as a seven year old, outdoors in the snow, and another taken by Daddy of the adult Miller. Thought-provoking and disturbing doesn’t get close; what might be the critical or readerly response if the poems here had been written by a male writer?

In the first sonnet,‘Strip’ we find the child Miller,

With eyes half closed

your frozen face pretends you’re feeling fine;

your angled body’s otherwise inclined

but he said strip, and so you did. Who knows?

Perhaps you’re numb. You turn and strike a pose.

The next sonnet, responding to Daddy’s adult nude, addresses Miller’s relation to her father,

It’s him

again: the father, tucked behind the lens

sharing his expertise. This is how it starts:

with naked lines and curves; it ends

with lessons in the darkroom. This is art.

You watch things develop, learn what you can.

You take what you can from any man.

We move on to a response to an image by Man Ray, its opening the last line of the poem just quoted. Here we see Miller learning to be an artist, specifically a woman artist in 1930s Paris. Then we find ourselves looking at one of Miller’s war photos, this one of Miller in Hitler’s bath, taken by David E. Scherman, Munich, 1945.

Your empty boots begin to stamp, you’re hungry

for more action: unbuckled, filthy, crushed,

a world apart. How did you come to this?

Other war photographs included here, by Miller herself, include one of a Bürgermeister’s daughter who had committed suicide, a beaten and traumatised SS guard, a shaven-head woman accused of being a Nazi collaborator, and a group of women in Dachau, part of an enforced camp brothel. This one is in quotes, as voiced by Miller

As if the storm inside can be erased

by acts of witness, I become the still eye;

empty, curious. I load the human freight

onto my film and let the image fly.

I must not think. I don’t discriminate,

and concludes

But I must tell:

I take it all. I focus, click, commit.

Miller’s notion of commitment while remaining objective, seems to distance itself from Isherwood’s passivity, and the 14th sonnet, a reading of another image of Miller by David E. Scherman, is worth quoting in full:

To win, you dig for mercy, shoot for grace

but catch yourself still standing in the ruins.

Today you found a dead man’s hand. Your face

betrays you: bitten, squinting, frankly human,

lips curled to a snarl, you’ve lost the will

to posture and transcend: another sort

of nakedness, the dead weight of your smile

has dropped. Feet in the mud, you’re caught

between the broken and the brave. Strung out,

dirty, you’re still the girl who trembled

in the snow wearing only silence. And now

she’s on your back, she shivers in your head,

and weeps into your skull: you want her gone,

but no. You square your shoulders, soldier on.

As a portrait of the woman artist, and the emotional and psychological price of making art, starting with being her father’s nude model, and going on to act as historical witness to Dachau and other atrocities, this is powerful without being overblown or hectoring. As a writer who engages with artwork in ekphrastic poems, your reviewer is well aware of the challenges involved, and could well imagine looking at any of the photographs in this book, and thinking ‘I can’t do this’ or starting then abandoning this sort of project. Saphra is to be commended for bring this sonnet sequence to such a successful conclusion, and Hercules Press applauded for making a fully considered book, with its informative and thought-provoking essays by Patricia Allmer and Jacqueline Saphra.

Mar 29 2018

London Grip Poetry Review – Saphra

Camera Eye / I, Camera: Brian Docherty considers Jacqueline Saphra’s poem sequence based on remarkable photographs of and by Lee Miller

Christopher Isherwood’s 1939 novel, Goodbye To Berlin, set in 1929, and the source for the Broadway musical, and 1972 film, Cabaret, opens with the narrator claiming

I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking. Recording the man shaving at the window opposite, and the woman in the kimono washing her hair. Some day, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed.Our reactions could include ‘Voyeurism’, ‘Why is this Art’, ‘People, especially women, being objectified’, ‘What about permission, or subject involvement’, ‘The Camera never lies’. ‘Oh really’, and so on. Isherwood’s model of photography clearly owes more to say, the type of photographs taken by Henri Cartier-Bresson, than to the landscapes of Ansel Adams. We might also note that some of the records issued under the name of Miles Davis, Bitches Brew for example, owe as much to the editorial creativity of producer Teo Macero, than to Davis. (There is a well-known anecdote about Davis walking into Columbia Records office, hearing some music playing, asking ‘What’s that?‘ and being told ‘That’s your new LP, Mr Davis.’) And that’s before we get to relatively simple techniques such as cropping, framing, tinting, re-touching and focussing.

Given that most early photographers were men, Julia Margaret Cameron being a notable exception, there is an immediate issue here, addressed by Laura Mulvey, bell hooks, Lorraine Gamman and others; see for example the British Journal of Photography BJP 7859: Female Gaze. Jacqueline Saphra’s book, the latest in Hercules Press’ exemplary series of publications, addresses some of these concerns in the introductory essay, ‘Lee Miller: Seer and Seen’ by Patricia Allmer, and in Saphra’s Introduction to the poems.

First, a note on the poems themselves, a sequence of 15 sonnets, a crown or corona of sonnets. This is in itself a notable achievement; those of us who write occasional sonnets, and struggle with the form, still the Gold Standard of English verse, can only applaud Saphra’s craft skills. As readers will know, this involves writing, in whatever order, 14 sonnets, then making the 15th sonnets from existing lines from the other 14.

Each of these sonnets is an ekphrastic response to a photograph either by Lee Miller, or of Lee Miller. Six images from Miller’s archives, two of Miller by David Scherman, one self-portrait, one nude portrait by Man Ray, one Miller family group by an unknown photographer, one of Miller and her mother, and two nudes taken by her father Theodore Miller. One of these is of Miller as a seven year old, outdoors in the snow, and another taken by Daddy of the adult Miller. Thought-provoking and disturbing doesn’t get close; what might be the critical or readerly response if the poems here had been written by a male writer?

In the first sonnet,‘Strip’ we find the child Miller,

With eyes half closed your frozen face pretends you’re feeling fine; your angled body’s otherwise inclined but he said strip, and so you did. Who knows? Perhaps you’re numb. You turn and strike a pose.The next sonnet, responding to Daddy’s adult nude, addresses Miller’s relation to her father,

It’s him again: the father, tucked behind the lens sharing his expertise. This is how it starts: with naked lines and curves; it ends with lessons in the darkroom. This is art. You watch things develop, learn what you can. You take what you can from any man.We move on to a response to an image by Man Ray, its opening the last line of the poem just quoted. Here we see Miller learning to be an artist, specifically a woman artist in 1930s Paris. Then we find ourselves looking at one of Miller’s war photos, this one of Miller in Hitler’s bath, taken by David E. Scherman, Munich, 1945.

Your empty boots begin to stamp, you’re hungry for more action: unbuckled, filthy, crushed, a world apart. How did you come to this?Other war photographs included here, by Miller herself, include one of a Bürgermeister’s daughter who had committed suicide, a beaten and traumatised SS guard, a shaven-head woman accused of being a Nazi collaborator, and a group of women in Dachau, part of an enforced camp brothel. This one is in quotes, as voiced by Miller

As if the storm inside can be erased by acts of witness, I become the still eye; empty, curious. I load the human freight onto my film and let the image fly. I must not think. I don’t discriminate,and concludes

But I must tell: I take it all. I focus, click, commit.Miller’s notion of commitment while remaining objective, seems to distance itself from Isherwood’s passivity, and the 14th sonnet, a reading of another image of Miller by David E. Scherman, is worth quoting in full:

To win, you dig for mercy, shoot for grace but catch yourself still standing in the ruins. Today you found a dead man’s hand. Your face betrays you: bitten, squinting, frankly human, lips curled to a snarl, you’ve lost the will to posture and transcend: another sort of nakedness, the dead weight of your smile has dropped. Feet in the mud, you’re caught between the broken and the brave. Strung out, dirty, you’re still the girl who trembled in the snow wearing only silence. And now she’s on your back, she shivers in your head, and weeps into your skull: you want her gone, but no. You square your shoulders, soldier on.As a portrait of the woman artist, and the emotional and psychological price of making art, starting with being her father’s nude model, and going on to act as historical witness to Dachau and other atrocities, this is powerful without being overblown or hectoring. As a writer who engages with artwork in ekphrastic poems, your reviewer is well aware of the challenges involved, and could well imagine looking at any of the photographs in this book, and thinking ‘I can’t do this’ or starting then abandoning this sort of project. Saphra is to be commended for bring this sonnet sequence to such a successful conclusion, and Hercules Press applauded for making a fully considered book, with its informative and thought-provoking essays by Patricia Allmer and Jacqueline Saphra.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2018 0 • Tags: books, Brian Docherty, poetry