Chris Beckett welcomes the arrival of a new collection from Julia Bird

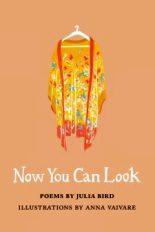

Now You Can Look

Julia Bird, with illustrations by Anna Vaivare

The Emma Press

ISBN 9781910139844

£10

Now You Can Look

Julia Bird, with illustrations by Anna Vaivare

The Emma Press

ISBN 9781910139844

£10

It’s not often I get the chance to quote myself, so here goes, from my London Grip review of Julia Bird’s last collection, Twenty Four Seven Blossom:

“…I would have liked…more of anything that Bird has chosen herself, out of her own

idiosyncratic menu of subject and style, her own important concerns and obsessions,

to entertain and trouble us, her readers. Which means, of course, that I am already

looking forward to her next book.”

And here it is, a beautiful pamphlet from The Emma Press with just 17 poems, but feeling a lot longer, partly because of the unsettling illustrations (more on these later); partly because the blurb tells you there are three ways to read the book before “you can look” (and what a blurb tells me to do, I do); but also because of Bird’s delightfully quirky eye for details like the girl’s “wart-struck feet” in the first poem, which make you linger and reread them, giving the poems exactly that stamp of Birdiness that I was looking for above.

The poems tell the story of a girl/young woman between the wars who rejects her parents’ sniffy parlour games world, where the servants are too low to name,

Someone comes to clear away the tea things

. (‘The Artist, Aged 9, Plays a Parlour Game’)

and becomes an artist and bohemian, maybe Bloomsbury, with all its associations of sexual and artistic liberation. She is confronted by different kinds of maleness, the young man whose fingers

possessed the necessary slenderness to pick a poppy from the roadside,

to pull its petals down to form a flower doll

. (‘A Note to a Friend Regarding the Young Man with Whom She Went for a Country Walk’)

then the art college assistant who kisses her in front of a huge and threatening polar bear in a taxidermist’s shop window:

three reflections – hers, the bear’s and his.

What looks like a bite is actually a kiss.

(‘The Assistant Escorts her the Long Way Home Through Town’)

Finally, my favourite two poems of the book witness her transformed, first by a haircut:

The bun unpinned, the plaits unwound,

her dark hair sluices to the chair seat.

…a tot of rag curls and pig tails…

Count four with the shears and it’s gone.

(‘Without Confiding in a Soul, She Goes to Get Her Hair Cut’)

then, by draping herself in a beautiful silk kimono, telling her lover not to look at

……………the spill

that isn’t silk but skin;

at the skin and curls;

at the curls and silk.

And now you can look.

. (‘She Stands in the Bedroom Doorway Wearing His Gift, Saying Don’t Look Yet…’)

This last poem seems especially central to the book; not only does it star the kimono from the cover, but it is bodily slim, page-centred, and directly addresses the act of looking which is an artist’s prime concern, Bird’s too. When and how to look is crucial, not just what you see but how you see it, through the poet’s description. The trick is to look at something you know, but see it transformed into what it really is: a girl without the distraction of her long hair, the erotic charge of a body glimpsed through a silk kimono. Bird’s soft voice in your ear feels like a magician’s patter, revelatory, playful, even outrageous (“the hem like cut / butter from an ice-box; …like the line of lamplight at a / voyeur’s door”).

However, the illustrations, each page of which is like a beautifully colourful wall-paper in a child’s bedroom, include nightmarish dead birds, bear claws, gas masks, ants in wine glasses etc as well as pretty flowers and dolls, paint brushes and pigtails. All is definitely not peachy in this arty free-loving world; jealousy and war are on the horizon and sure enough eggs rupture on the flag floor (‘She Makes Omelettes at 1 p.m. on a Sunday’), something in the artist’s home (and heart) is burning (‘The Artist in a Field in November’), and finally a bomb falls on Maple Villa (‘A Bomb Damage Report’).

This is an intriguing book, beautiful both visually and poetically, a book which I suggest will make a wonderful Christmas gift, because of its charm, yes, but also because of its bite.

Nov 29 2017

Chris Beckett welcomes the arrival of a new collection from Julia Bird

It’s not often I get the chance to quote myself, so here goes, from my London Grip review of Julia Bird’s last collection, Twenty Four Seven Blossom:

And here it is, a beautiful pamphlet from The Emma Press with just 17 poems, but feeling a lot longer, partly because of the unsettling illustrations (more on these later); partly because the blurb tells you there are three ways to read the book before “you can look” (and what a blurb tells me to do, I do); but also because of Bird’s delightfully quirky eye for details like the girl’s “wart-struck feet” in the first poem, which make you linger and reread them, giving the poems exactly that stamp of Birdiness that I was looking for above.

The poems tell the story of a girl/young woman between the wars who rejects her parents’ sniffy parlour games world, where the servants are too low to name,

Someone comes to clear away the tea things . (‘The Artist, Aged 9, Plays a Parlour Game’)and becomes an artist and bohemian, maybe Bloomsbury, with all its associations of sexual and artistic liberation. She is confronted by different kinds of maleness, the young man whose fingers

to pull its petals down to form a flower doll . (‘A Note to a Friend Regarding the Young Man with Whom She Went for a Country Walk’)then the art college assistant who kisses her in front of a huge and threatening polar bear in a taxidermist’s shop window:

Finally, my favourite two poems of the book witness her transformed, first by a haircut:

then, by draping herself in a beautiful silk kimono, telling her lover not to look at

……………the spill that isn’t silk but skin; at the skin and curls; at the curls and silk. And now you can look. . (‘She Stands in the Bedroom Doorway Wearing His Gift, Saying Don’t Look Yet…’)This last poem seems especially central to the book; not only does it star the kimono from the cover, but it is bodily slim, page-centred, and directly addresses the act of looking which is an artist’s prime concern, Bird’s too. When and how to look is crucial, not just what you see but how you see it, through the poet’s description. The trick is to look at something you know, but see it transformed into what it really is: a girl without the distraction of her long hair, the erotic charge of a body glimpsed through a silk kimono. Bird’s soft voice in your ear feels like a magician’s patter, revelatory, playful, even outrageous (“the hem like cut / butter from an ice-box; …like the line of lamplight at a / voyeur’s door”).

However, the illustrations, each page of which is like a beautifully colourful wall-paper in a child’s bedroom, include nightmarish dead birds, bear claws, gas masks, ants in wine glasses etc as well as pretty flowers and dolls, paint brushes and pigtails. All is definitely not peachy in this arty free-loving world; jealousy and war are on the horizon and sure enough eggs rupture on the flag floor (‘She Makes Omelettes at 1 p.m. on a Sunday’), something in the artist’s home (and heart) is burning (‘The Artist in a Field in November’), and finally a bomb falls on Maple Villa (‘A Bomb Damage Report’).

This is an intriguing book, beautiful both visually and poetically, a book which I suggest will make a wonderful Christmas gift, because of its charm, yes, but also because of its bite.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 1 • Tags: books, Chris Beckett, poetry