Thomas Ovans looks at myth and reality as handled in a debut pamphlet from Kitty Coles

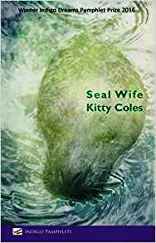

Seal Wife

Kitty Coles

Indigo Dreams Publishing

ISBN 9781910834572

36pp £6

Seal Wife

Kitty Coles

Indigo Dreams Publishing

ISBN 9781910834572

36pp £6

This – the second debut chapbook I have reviewed within a week or two – is very different from the previous one which was strongly rooted in the recognisable everyday world. The prize-winning pamphlet Seal Wife by Kitty Coles is, by contrast, deeply immersed in myth and fantasy and only occasionally – but very interestingly – ventures into what the reader might call ‘real life’. The tone is set in the first poem ‘Forest’ – which might almost be a prospectus for the book

Either you don’t go into the dark forest

or you go

and you go unarmed.

There may be potential readers who do not usually relish poetry that deals with fairy tales and legends. Unless they lay aside a few preconceptions (and “go unarmed” into these poems) they may miss some fine examples of apt and atmospheric language. Coles gives us poems of transformation like ‘The Doe-Girl’ whose eyes “once blue, / turned black all over, / like ink spreading through water.” The speaker in ‘Green Girl’ wonders

If I hold still enough,

stare long enough

at the candle flame’s

black smokes like veils,

can I arrest

the scutter of

my rabbit heart...?

And in the title poem the Seal Wife, unhappy on land and unable to forget the water that still claims her, observes “the grass is aching with frost. / Birds fall, small toys, / from the trees in their deaths.”

‘Seal Wife’ is paired with ‘Lighthouse Keeper’ which tells a complementary story from the human being’s point of view

I watch the seals emerging by the rocks

...

The sheen of their flanks

is oily, voluptuous. I watch

all night but you are never among them.

Such a sensuous phrase that “oily, voluptuous”!

If transformation is one recurring theme then another is intrusion. ‘A Soul’ begins by asking innocently enough “Is that your soul you hold in your hand, / as small as a walnut?” but comes to the threatening realization that “You would have me open my mouth / and swallow it.” Worse still

It would lodge in my stomach,

lodge in and nestle,

a dainty mouse seeking shelter.

‘Poltergeist’ presents another kind of intruder who seems more in tune with the modern world than many fairy-tale ghosts: “I deliver myself, / with a thump, through the letterbox”; “On the steam of the bathroom mirror, / I write your name and mine.” But (perhaps for the sake of balance?) Coles also considers ways of dealing with such unwanted interlopers. ‘On the Capturing of Ghosts’ tells us to “call him by name, the syllables / that still shape him”; and ‘Exorcism’ gives a staccato account of the work of the exorcist: “The house hums with your work. Their black blood / is scentless. You scrub it from the floors. / The wood wears thin.”

The experience of actually being the frightening intruder is conveyed in ‘Life Undead’ (which provides a welcome injection of humour)

In the absence of a grim ancestral pile

in the Carpathians, you find yourself

working all hours to pay the bills, the rent

There are relatively few poems in which Coles engages with the everyday world; but when she does so she approaches the familiar with the same heightened imagination that belongs to the myths and fantasies she is mainly concerned with. ‘The Seeds of the Pomegranate’ makes something rather terrifying of the sharing of a piece of fruit. “You halve it and the blade / forces apart the grisly mass of jewels./ You hack, they bleed, fight to retain their wholeness.”

‘The Butcher’s Wife’ is a particularly evocative ‘real life’ poem – not least because Coles might have unwittingly stumbled upon the spouse of the butcher in the much-anthologised poem by Hugo Wiliams who is a rosy young man with white eyelashes / like a bullock. Coles’s butcher is splendidly fleshed-out: his hands have a “network of veins” which “shows through as clear as a blueprint” and “the nails are kept short./ He uses a brutal brush // to scour under them.”

‘The Huntsman’s Wife’ initially tricks us into believing that it is a similar poem to the one previously mentioned – that is, a romanticised account of a relatively ordinary situation which in this case involves matter of fact preparations in a stable yard where an old horse “has woken himself and his breath damps both our faces.” The seemingly mundane continues: “Good wife, I brush and comb him like a child”; “You nod to me and mount.” But then the last verse springs its surprises from the dazzling opening line “Out in the yard, the air is stiff with stars” to its chilling final one “I wait all night to see the soul you’ll bring me.”

I have so far sought to give the full credit which is amply deserved by individual poems. I have to say however that the collection as a whole seems to me to suffer from an over-investment in the uncanny and supernatural. The narrative poetic voice, whether using the first or the third person, does not seem to vary very much and there are too many, rather similar, poems about transformations and the like. A number of pieces like ‘Black Annis’ and ‘Ceridwen’ evidently refer to figures from various folk-lore traditions; but the absence of any explanatory notes meant that it was hard for this reader to distinguish between them.

It is unfortunate but necessary for me to make the preceding negative comments; but they are not intended to detract at all from the positive views expressed in the major part of this review. Kitty Coles clearly has a powerful imagination, a good ear and can make very creative use of language. If she can begin to increase her range then her future collections will be something to look forward to.

Oct 9 2017

Thomas Ovans looks at myth and reality as handled in a debut pamphlet from Kitty Coles

This – the second debut chapbook I have reviewed within a week or two – is very different from the previous one which was strongly rooted in the recognisable everyday world. The prize-winning pamphlet Seal Wife by Kitty Coles is, by contrast, deeply immersed in myth and fantasy and only occasionally – but very interestingly – ventures into what the reader might call ‘real life’. The tone is set in the first poem ‘Forest’ – which might almost be a prospectus for the book

There may be potential readers who do not usually relish poetry that deals with fairy tales and legends. Unless they lay aside a few preconceptions (and “go unarmed” into these poems) they may miss some fine examples of apt and atmospheric language. Coles gives us poems of transformation like ‘The Doe-Girl’ whose eyes “once blue, / turned black all over, / like ink spreading through water.” The speaker in ‘Green Girl’ wonders

And in the title poem the Seal Wife, unhappy on land and unable to forget the water that still claims her, observes “the grass is aching with frost. / Birds fall, small toys, / from the trees in their deaths.”

‘Seal Wife’ is paired with ‘Lighthouse Keeper’ which tells a complementary story from the human being’s point of view

If transformation is one recurring theme then another is intrusion. ‘A Soul’ begins by asking innocently enough “Is that your soul you hold in your hand, / as small as a walnut?” but comes to the threatening realization that “You would have me open my mouth / and swallow it.” Worse still

‘Poltergeist’ presents another kind of intruder who seems more in tune with the modern world than many fairy-tale ghosts: “I deliver myself, / with a thump, through the letterbox”; “On the steam of the bathroom mirror, / I write your name and mine.” But (perhaps for the sake of balance?) Coles also considers ways of dealing with such unwanted interlopers. ‘On the Capturing of Ghosts’ tells us to “call him by name, the syllables / that still shape him”; and ‘Exorcism’ gives a staccato account of the work of the exorcist: “The house hums with your work. Their black blood / is scentless. You scrub it from the floors. / The wood wears thin.”

The experience of actually being the frightening intruder is conveyed in ‘Life Undead’ (which provides a welcome injection of humour)

There are relatively few poems in which Coles engages with the everyday world; but when she does so she approaches the familiar with the same heightened imagination that belongs to the myths and fantasies she is mainly concerned with. ‘The Seeds of the Pomegranate’ makes something rather terrifying of the sharing of a piece of fruit. “You halve it and the blade / forces apart the grisly mass of jewels./ You hack, they bleed, fight to retain their wholeness.”

‘The Butcher’s Wife’ is a particularly evocative ‘real life’ poem – not least because Coles might have unwittingly stumbled upon the spouse of the butcher in the much-anthologised poem by Hugo Wiliams who is a rosy young man with white eyelashes / like a bullock. Coles’s butcher is splendidly fleshed-out: his hands have a “network of veins” which “shows through as clear as a blueprint” and “the nails are kept short./ He uses a brutal brush // to scour under them.”

‘The Huntsman’s Wife’ initially tricks us into believing that it is a similar poem to the one previously mentioned – that is, a romanticised account of a relatively ordinary situation which in this case involves matter of fact preparations in a stable yard where an old horse “has woken himself and his breath damps both our faces.” The seemingly mundane continues: “Good wife, I brush and comb him like a child”; “You nod to me and mount.” But then the last verse springs its surprises from the dazzling opening line “Out in the yard, the air is stiff with stars” to its chilling final one “I wait all night to see the soul you’ll bring me.”

I have so far sought to give the full credit which is amply deserved by individual poems. I have to say however that the collection as a whole seems to me to suffer from an over-investment in the uncanny and supernatural. The narrative poetic voice, whether using the first or the third person, does not seem to vary very much and there are too many, rather similar, poems about transformations and the like. A number of pieces like ‘Black Annis’ and ‘Ceridwen’ evidently refer to figures from various folk-lore traditions; but the absence of any explanatory notes meant that it was hard for this reader to distinguish between them.

It is unfortunate but necessary for me to make the preceding negative comments; but they are not intended to detract at all from the positive views expressed in the major part of this review. Kitty Coles clearly has a powerful imagination, a good ear and can make very creative use of language. If she can begin to increase her range then her future collections will be something to look forward to.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, poetry, Thomas Ovans