D A Prince finds the poems of Robert Etty to be very good company as they explore Lincolnshire’s landscape and introduce its people

Passing the Story Down the Line

Robert Etty

Shoestring Press, 2017

ISBN 978-1-910323-79-3

94 pp. £10

Passing the Story Down the Line

Robert Etty

Shoestring Press, 2017

ISBN 978-1-910323-79-3

94 pp. £10

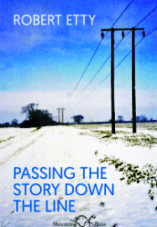

The cover image matches the title: flat Lincolnshire, a few bare trees, enough snow to almost cover the grass, and a line of pylons carrying their wires to beyond the horizon. It looks nothing much, yet if this is your landscape it is everything, and Etty has always celebrated Lincolnshire in his poetry. It’s not just that he has lived and worked here all his life; he is a poet who looks to the familiar, finds richness in the daily routines, and listens to the distinctive qualities in the people whose lives he knows. Their stories are passed on through the lines of these poems as electricity travels down the wires – indicative of the light-touch word-play that Etty employs, partly as entertainment but also as an exploration of vernacular language that is sometimes ours, sometimes Lincolnshire’s. He has a keen ear for humour and sharp observation of continuity in communities a long way from London. This might be his ninth collection but there is no slackening in his technique.

Down-to-earth yet with an appreciation of something transcendental in the ordinary: it’s all there in ‘A Winter Eclipse in the Co-op Car Park’, the opening poem. Winter, and a dull morning until the sun rises over an advertising hoarding, gilding everything and everyone –

and, even squinting, I recognise none

of the haloed, semi-translucent shoppers.

When the right size of slowing bus blocks out

the real sun, an angel I’d spotted hovering ahead

turns out to be only Alan Alcock,

who’s no more unearthly than average,

but whose radiant hair and breath have been putting

a different complexion on matters.

They do it again when the bus pulls away

and the essence of Alan re-emerges,

if not as ineffably. ‘All right?’

he asks me, demystified now, yet still

not quite as he used to be.

That’s a long quotation but Etty isn’t a catchy-soundbite poet so only a longer extract will do justice to his technique; he builds up his poems slowly, letting the reader go through the same visual process that he describes. This scene has much in common with Stanley Spencer’s Cookham paintings where ordinary people are transfigured, momentarily, though with less of Spencer’s obviously religious purpose. There is, however, just enough religious vocabulary slipped in here – halo-ed, angel, unearthly, for example – to lift the poem into that same semi-religious register. The feeling that even the Co-op car-park can hold the possibility of a spiritual experience, however low-key, re-arranges our expectations. Etty’s language is colloquial and seems effortless but it takes confidence to write phrases like ‘the right size of slowing bus’ and ‘no more unearthly than average’, and to slip ‘ineffably’ into the narrative as though it is one of the easiest words to use. Not just Alan Alcock but language suddenly examines its own doubled meaning – here, ’a different complexion’, and this is a foretaste of the word-play that will be a feature of subsequent poems – none of it laboured but all of it lightly shared. Almost every page offers an example, as here, from ‘After You Didn’t Answer the Phone’ –

The unanswered phone has a great deal

to answer for where our particular history’s

concerned.

It’s better than banter and wittier than jokey; it’s the lightness of a poet who fits a companionable wit into the small exchanges of everyday routines, and knows how to balance the weight of one word against another. While Lincolnshire and its landscape is present throughout the four sections of this collection, it’s the people who inhabit the small town and countryside that engage Etty’s attention. They are named, giving the poems a deeper sense of reality – although whether they are literally ‘real’ I doubt. There’s ‘Mavis Bream from the terrace opposite / the carpet store at the top of the hill’ who tends her cascades of fuchsias (‘Upwards and Upwards’). Leslie Nesbitt (in ‘All-Time Football Story’) invents a past in which he was ‘…Sheffield Wednesday’s / all-time top-scoring outside-left …’

but it left me with doubts about adults,

face values, trust, Sheffield Wednesday

and what you should say about yourself.

Etty uses these childhood experiences and their preparation for adult life to great effect. ‘Office Workers in the Gateway to the Last Field on Cow Pasture Lane’ moves between the lovers in parked cars – ‘A Hillman or Rover …’ – everything at the start of the poem is as exact as its title – Keith Madsen, who ‘cowboyed the milkers’ and so knew the routines , and ‘… Martin’s book / on Growing Up’ to show the various ways that sexual knowledge was built up. Pre-internet, there is an innocent comedy in this rural education:

In due course, the car would shudder gently,

cough and reverse in a practised way,

and leave with an air of shared achievement

and sensitive manual choke.

Continuity of place and time, along with the accumulated detail acquired by those who live in one place, is something Etty shares and values while recognising, implicitly, that this is increasingly rare. ‘London’ defines the capital by its opening negative –

London’s a place Raymond’s never been. He says

‘What the hell should I do if I went?’ He once

set out in the van for St Neots, but decided

in Sleaford he’d save the petrol.

The rhythmic repetitions at the line ends – ‘He says’ and ‘He once’ – suggest that small interruption of time, that eruption of quickly-abandoned desire, which dissolved into staying close to home. After the first line, London disappears entirely, and the poem focusses on the poet asking Raymond about specifics, if he can name the trees along a ditch a couple of miles away –

’Hornbeam’, he’s saying, before I’ve finished.

‘Then four biggish ash, some deep pink dog roses,

an old wild apple the wasps nest under,

then sycamores, with hundreds of rooks.

Years I worked up there, ploughing and drilling.

So much going on round me I couldn’t keep pace.’

While I’ve admired Etty’s poetry since first encountering it in the 1990’s (when he was also the co-editor of Seam magazine, and had pamphlets – as I did – published by Pikestaff Press) this is the first full collection I’ve read. Fortunately I now have time to fill in the gaps. It has proved very good company, not only for the stories and humour, but for the way in which Etty can work with language to make it playful, and both sad and funny at the same time. It’s accessible in the best sense: human life, in its variety and unpredictability, explored through a consistent generosity of spirit and insight.

D A Prince finds the poems of Robert Etty to be very good company as they explore Lincolnshire’s landscape and introduce its people

The cover image matches the title: flat Lincolnshire, a few bare trees, enough snow to almost cover the grass, and a line of pylons carrying their wires to beyond the horizon. It looks nothing much, yet if this is your landscape it is everything, and Etty has always celebrated Lincolnshire in his poetry. It’s not just that he has lived and worked here all his life; he is a poet who looks to the familiar, finds richness in the daily routines, and listens to the distinctive qualities in the people whose lives he knows. Their stories are passed on through the lines of these poems as electricity travels down the wires – indicative of the light-touch word-play that Etty employs, partly as entertainment but also as an exploration of vernacular language that is sometimes ours, sometimes Lincolnshire’s. He has a keen ear for humour and sharp observation of continuity in communities a long way from London. This might be his ninth collection but there is no slackening in his technique.

Down-to-earth yet with an appreciation of something transcendental in the ordinary: it’s all there in ‘A Winter Eclipse in the Co-op Car Park’, the opening poem. Winter, and a dull morning until the sun rises over an advertising hoarding, gilding everything and everyone –

That’s a long quotation but Etty isn’t a catchy-soundbite poet so only a longer extract will do justice to his technique; he builds up his poems slowly, letting the reader go through the same visual process that he describes. This scene has much in common with Stanley Spencer’s Cookham paintings where ordinary people are transfigured, momentarily, though with less of Spencer’s obviously religious purpose. There is, however, just enough religious vocabulary slipped in here – halo-ed, angel, unearthly, for example – to lift the poem into that same semi-religious register. The feeling that even the Co-op car-park can hold the possibility of a spiritual experience, however low-key, re-arranges our expectations. Etty’s language is colloquial and seems effortless but it takes confidence to write phrases like ‘the right size of slowing bus’ and ‘no more unearthly than average’, and to slip ‘ineffably’ into the narrative as though it is one of the easiest words to use. Not just Alan Alcock but language suddenly examines its own doubled meaning – here, ’a different complexion’, and this is a foretaste of the word-play that will be a feature of subsequent poems – none of it laboured but all of it lightly shared. Almost every page offers an example, as here, from ‘After You Didn’t Answer the Phone’ –

It’s better than banter and wittier than jokey; it’s the lightness of a poet who fits a companionable wit into the small exchanges of everyday routines, and knows how to balance the weight of one word against another. While Lincolnshire and its landscape is present throughout the four sections of this collection, it’s the people who inhabit the small town and countryside that engage Etty’s attention. They are named, giving the poems a deeper sense of reality – although whether they are literally ‘real’ I doubt. There’s ‘Mavis Bream from the terrace opposite / the carpet store at the top of the hill’ who tends her cascades of fuchsias (‘Upwards and Upwards’). Leslie Nesbitt (in ‘All-Time Football Story’) invents a past in which he was ‘…Sheffield Wednesday’s / all-time top-scoring outside-left …’

Etty uses these childhood experiences and their preparation for adult life to great effect. ‘Office Workers in the Gateway to the Last Field on Cow Pasture Lane’ moves between the lovers in parked cars – ‘A Hillman or Rover …’ – everything at the start of the poem is as exact as its title – Keith Madsen, who ‘cowboyed the milkers’ and so knew the routines , and ‘… Martin’s book / on Growing Up’ to show the various ways that sexual knowledge was built up. Pre-internet, there is an innocent comedy in this rural education:

Continuity of place and time, along with the accumulated detail acquired by those who live in one place, is something Etty shares and values while recognising, implicitly, that this is increasingly rare. ‘London’ defines the capital by its opening negative –

The rhythmic repetitions at the line ends – ‘He says’ and ‘He once’ – suggest that small interruption of time, that eruption of quickly-abandoned desire, which dissolved into staying close to home. After the first line, London disappears entirely, and the poem focusses on the poet asking Raymond about specifics, if he can name the trees along a ditch a couple of miles away –

While I’ve admired Etty’s poetry since first encountering it in the 1990’s (when he was also the co-editor of Seam magazine, and had pamphlets – as I did – published by Pikestaff Press) this is the first full collection I’ve read. Fortunately I now have time to fill in the gaps. It has proved very good company, not only for the stories and humour, but for the way in which Etty can work with language to make it playful, and both sad and funny at the same time. It’s accessible in the best sense: human life, in its variety and unpredictability, explored through a consistent generosity of spirit and insight.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, D A Prince, poetry