James Roderick Burns reflects on the multiple goals a poetry anthology editor has to aim for – and considers that Alison Hill has done pretty well with her selection of flying-related poems

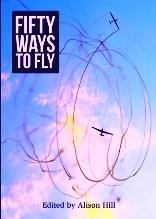

Fifty Ways to Fly

Alison Hill, Editor

Rhythm & Muse, 2017

£8.99

Fifty Ways to Fly

Alison Hill, Editor

Rhythm & Muse, 2017

£8.99

Getting the consistency, tone and overall achievement of an anthology right is tricky: if it is a poetry anthology, your likely audience is a finicky one (people who appreciate poetry and are prepared to pay for it, as well as other poets) and will have a long line of other volumes in mind when they sit down to read. If a fiction anthology, the audience is more likely to engage on the basis of an established theme or genre (think ghost stories, crime writing, science fiction) and bring along a host of ingrained expectations which have to be met. And if the book is a themed poetry anthology – and moreover one like Fifty Ways to Fly, sold in aid of a voluntary body supporting a good cause, in this case the British Women Pilots’ Association – the task and audience become harder still. Now the person picking up the book must like poetry, be willing to pay for it, have come with a pre-existing interest in the subject matter and knowing the purchase will assist a voluntary body, finish the book with their appreciation and understanding shored up (preferably then heading on to the charity’s website to find out more). It is a huge ask of any editor.

Alison Hill has done well to meet all of these expectations. Fifty Ways to Fly isn’t perfect – the inclusion of song lyrics, and work by people more associated with the heroic historical achievements of some of the poems than with poetry itself, means the quality is necessarily uneven – but achieves something across each of these three demands. There is poetry here, with some being of the highest quality; there is subtle extension of the idea of flight into new conceptual realms, as well as a wealth of work exploring the direct experience of flight; and there are moments of real tenderness in lives spent among the clouds.

Jackie Moggridge, for instance, captures the tension of early flight as both liberation into new life, and in new dangers, its implicit end:

How can I tell the distance and the time

or weather on the way?

Or estimate the height I have to climb

until I land some day?

Pray that the Master Pilot of us all will

check my course to steer

and not allow my wavering wings to stall

when I take off from here.

(‘The Last Flight’)

Other poems take the notion of flight and do interesting things with it: flying as a bridge from the living to the dead (Ronnie Goodyer’s ‘Selective Flying’ – “One such selective flying day/they will teach me to become spindrift”); as the engine of affection, or possibly its absence, in Michael Bartholomew-Biggs’ ‘Learning to Fly’ – “Blossom wonders/what it feels like to be falling, spinning into love”; or even a figuring of all the death and evil that can come roaring out of even the bluest sky:

Butterflies fly towards the clouds.

Pit themselves against the netting,

Flutter down, helter-skelter,

like sheaves of propaganda leaflets

from army helicopters,

corpses in the river or by the road,

young girls, dressed up for the night’s

narco fiestas, with bullets in their skulls.

(Isabel Bermudez, ‘The Butterfly House (Quindio, Colombia)’)

The book has its points of failure, too: Lynn Woollacott’s interesting concrete poem ‘Icelandic V’ presents two diverging paths of geese, first to reflection in church windows and then the water of an estuary, at the two opposing points of a ‘V’ which spreads across both pages; a nice conceit, but one which doesn’t quite hold up when the words are extracted from the form and left to stand on their own. Similarly (and unfortunately), the title piece by Maggie Sawkins is a rather bland list poem. ‘Fifty Ways to Fly’ does not rise very much above its opening line “1. Launch yourself from Ben Nevis” and for it to occupy such a prominent place in the book is disappointing.

However, such weaker material is rare; overall, the spirit of the anthology is positive and uplifting. Most of the work begins with some well-known aspect of the experience of flight and takes the reader to a new, interesting or moving place, and in the best poems, to all three. Rebecca Gethin’s ‘Gathering’ sums it up best. Describing the unaccountable, shifting patterns of flocks of birds, it shows how even the most disturbing events, when they follow the impulses of flight, can recombine into something beautiful and affirming:

the fields are bolts of cloth

wrinkling with birds

until a stray thread is pulled

and half of the flock

folds itself over the other

to crease and quarter

new ground

while trees on the margin

are thick with their singing

James Roderick Burns reflects on the multiple goals a poetry anthology editor has to aim for – and considers that Alison Hill has done pretty well with her selection of flying-related poems

Getting the consistency, tone and overall achievement of an anthology right is tricky: if it is a poetry anthology, your likely audience is a finicky one (people who appreciate poetry and are prepared to pay for it, as well as other poets) and will have a long line of other volumes in mind when they sit down to read. If a fiction anthology, the audience is more likely to engage on the basis of an established theme or genre (think ghost stories, crime writing, science fiction) and bring along a host of ingrained expectations which have to be met. And if the book is a themed poetry anthology – and moreover one like Fifty Ways to Fly, sold in aid of a voluntary body supporting a good cause, in this case the British Women Pilots’ Association – the task and audience become harder still. Now the person picking up the book must like poetry, be willing to pay for it, have come with a pre-existing interest in the subject matter and knowing the purchase will assist a voluntary body, finish the book with their appreciation and understanding shored up (preferably then heading on to the charity’s website to find out more). It is a huge ask of any editor.

Alison Hill has done well to meet all of these expectations. Fifty Ways to Fly isn’t perfect – the inclusion of song lyrics, and work by people more associated with the heroic historical achievements of some of the poems than with poetry itself, means the quality is necessarily uneven – but achieves something across each of these three demands. There is poetry here, with some being of the highest quality; there is subtle extension of the idea of flight into new conceptual realms, as well as a wealth of work exploring the direct experience of flight; and there are moments of real tenderness in lives spent among the clouds.

Jackie Moggridge, for instance, captures the tension of early flight as both liberation into new life, and in new dangers, its implicit end:

Other poems take the notion of flight and do interesting things with it: flying as a bridge from the living to the dead (Ronnie Goodyer’s ‘Selective Flying’ – “One such selective flying day/they will teach me to become spindrift”); as the engine of affection, or possibly its absence, in Michael Bartholomew-Biggs’ ‘Learning to Fly’ – “Blossom wonders/what it feels like to be falling, spinning into love”; or even a figuring of all the death and evil that can come roaring out of even the bluest sky:

The book has its points of failure, too: Lynn Woollacott’s interesting concrete poem ‘Icelandic V’ presents two diverging paths of geese, first to reflection in church windows and then the water of an estuary, at the two opposing points of a ‘V’ which spreads across both pages; a nice conceit, but one which doesn’t quite hold up when the words are extracted from the form and left to stand on their own. Similarly (and unfortunately), the title piece by Maggie Sawkins is a rather bland list poem. ‘Fifty Ways to Fly’ does not rise very much above its opening line “1. Launch yourself from Ben Nevis” and for it to occupy such a prominent place in the book is disappointing.

However, such weaker material is rare; overall, the spirit of the anthology is positive and uplifting. Most of the work begins with some well-known aspect of the experience of flight and takes the reader to a new, interesting or moving place, and in the best poems, to all three. Rebecca Gethin’s ‘Gathering’ sums it up best. Describing the unaccountable, shifting patterns of flocks of birds, it shows how even the most disturbing events, when they follow the impulses of flight, can recombine into something beautiful and affirming:

the fields are bolts of cloth wrinkling with birds until a stray thread is pulled and half of the flock folds itself over the other to crease and quarter new ground while trees on the margin are thick with their singingBy Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, James Roderick Burns, poetry