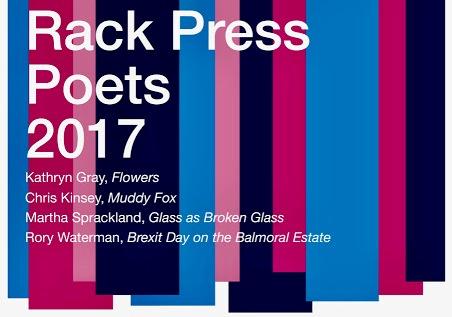

London Grip reviews four recent poetry pamphlets from Rack Press

Alex Josephy on Flowers by Kathryn Gray

.

Alex Josephy on Flowers by Kathryn Gray

.

A poetry pamphlet is often a beautiful thing to hold as well as to read. Printed on delicately-ribbed cream pages inside a grey cover worthy of Farrow and Ball, Kathryn Gray’s Flowers is a good example.

The opening poem’s title, ‘The Meet-Cute’, sent me straight to Duck-Duck-Go for a definition; it turns out to be the term for a particular kind of romantic meeting on film or TV, and set me on track for a sequence of poems that refer to and riff off a range of cultural and counter-cultural texts from film, TV, comedy and pop music. Specifically located in time and place, this field of reference might prove daunting to anyone who hasn’t seen the films or heard the music (I had more homework to do in order to untangle the Ferris Bueller and Breakfast Club characters who inhabit two of the poems). But Gray knows how to use these references to illuminate themes of real longing and pain, a more profound coming-of-age. In the first stanza of ‘The Meet-Cute’, she describes how, in a scene from a romantic film,

large rain renders gutters elaborate; their fretwork

fugitive, an offering to the lost and low of this world

and I’m won over immediately. Throughout the nine poems, the world of mass media provides landscapes in which Gray moves deftly between irony and painful honesty. No coincidence that cult comedian Bill Hicks features in the second poem, a kind of elegy; Gray writes of a powerful connection:

What freight passed between us.

Such sorrow in our final cigarette.

This small selection ranges quite widely and with great confidence in terms of form: each poem seems effortlessly fitted into the shape that suits it best. There are eight- and four-line stanzas made out of fluent, developed sentences; taut couplets and tercets; a prose poem; and more relaxed, sprawling lines that convey a conversational tone. There is a darkly witty poem, ‘I am the world’s last barman poet’ constructed around the names of (fictional?) cocktails: the Irish Car Bomb… The Four Horsemen.

I particularly like ‘Bournemouth’, addressed to “an imaginary friend”, the poet Rosemary Tonks (known in her reclusive final years as Mrs Lightband), in which the speaker describes a mind that “turns…/folds itself/over and over” like an “endless, sentient/serviette”. Internal and end rhyme and subtle rhythmic effects push the poem gently toward a marvellous conclusion where it is hard to discern whose tears “will be nothing new, while the stars– /our startlers– the stars impossibly accrue”.

In other ways accessible, these poems do rely on a specialised area of knowledge and in that sense, for this reader, they have at times a cryptic quality. The final poem is a good example: it reveals the origin of the pamphlet’s title– as surprising as many other facets of a sequence that combines pin-sharp intelligence with a touching vulnerability. I will leave the precise reference for readers to discover for themselves. The pamphlet comes to an end on the word ‘flowers’; it means something rather different from what you might expect.

.

Peter Daniels on Muddy Fox by Chris Kinsey

Peter Daniels on Muddy Fox by Chris Kinsey

Chris Kinsey makes poems that show nature vividly and often unexpectedly. She knows a lot about nature and wants to record the creatures, especially birds, and how they make impressions on her which she can interpret for the reader – sometimes briefly, a moment encapsulated like a haiku though longer: the nine lines of ‘Injured Angels’, which are whooper swans; the four five-line stanzas of ‘For a Friend Facing Surgery’, each a separate bird encounter, starting with “I send you the dipper, not genuflecting / to the rock, but bowing to appetite”. Animal behaviour is often described in terms like that one, not necessarily anthropomorphic but borrowing an image from the human world, like “swallows soar and flip, stropping / themselves on the clear sky” (‘For a Friend Facing Surgery’), or “I watched herons’ silent flamenco”(‘Muddy Fox’) – an image I find harder to appreciate, because unlike the stropping movement, the flamenco is more complex to imagine, with the added distancing of ‘silent’ so unlike the real life dancing.

On the whole I wish the imagery was kept simpler, as poems I otherwise like are weighed down with decorative embroidery, and words and images sometimes draw attention from the subject instead of illuminating it. It shouldn’t be impossible to use words like ‘azure’ or ‘cerulean’ – no word should be impossible – but they overbalance this:

Nothing in the church’s stained glass

or heavenly ceiling compared with the flash

of azure damselflies on clear leaded wings,

or the cerulean lake’s mirrored clouds

(Trompe l’oeil’)

These are “things I missed as a child – I was too avid to see / and hadn’t learnt to hold my shadow off the water.” I feel the poet’s shadow is a little too much on the water of her poems, in the form of belief that the world is there to be made into poems whether it wants to be or not. That comes especially in ‘Busker’, where the violinist “conjures more than he knows”, as if the poet’s interpretation is of more importance than the music itself.

In some of the best poems, nature is participating in the relationship with other people: her mother as a girl gathering wimberries, as she also does (‘Wimberries’), or the title poem with its tone of displaced worry for the cycling companion setting off for chemotherapy while she cleans her Muddy Fox bike, in the hope of riding together next March. And the observations of nature are constantly showing us things we might not know about the world around us, so are worth reading for that.

.

Graham Hardie on Glass As Broken Glass by Martha Sprackland.

Graham Hardie on Glass As Broken Glass by Martha Sprackland.

Martha Sprackland’s short pamphlet, Glass As Broken Glass is her first and it shows her to be a poet of considerable creative powers, with astute diction and use of imagery, together with a tranquil repose in the sense of time and place. The pamphlet contains eight poems dealing with subjects ranging from a trip to a museum to a man who holds the record for surviving being hit by lightning. It is a shame that a short pamphlet does not allow particular themes and narratives to flourish or be nurtured to full development, and very occasionally the author can over use language to the slight detriment of the poem and her poetic voice.

The first poem “Snail” opens with the line “I caved him in with the heel of my shoe”; however, it seems, this leaves “the job half-done,” and there are anxious pangs of regret and remorse: Unless “ I bring my foot down hard again/ … I know with absolute certainty / that it will follow me where I go” This is a frank and honest poem taking on the sentimentality associated with love and death .

The second poem is about the poet’s visit to the Hunterian museum in Glasgow with its “ghostly archive”, whch includes “silver birch leaves in the moonlight, and the teeth / and textbook jaws and joints of elephants and antelope”. Images like “Black malignancies glued inside the ribcage like wasps’ nests,” succeed in conveying the eerie atmosphere of the museum.

Elsewhere the poet describes the No 38 bus “blaring like a drunk as it rolls away to town.” Having dropped her phone at a bus-stop, she stares at it on the ground, “both smashed and not-smashed” and reminding her of “the robin egg child-me found down at the rec”. Again the poet is at ease with her subject matter as she expresses the emotion behind the experience.

“Tricksters Shark and Selkie” opens with the lines “Shark won’t be fooled by the lure/in sealskin black towed behind the motorboat” and continues with some fine, articulate phrases like “the skyscraper stands of kelp/as back-alley and shadow” However, this was the one poem where arguably the poet is slightly too convoluted in her use of language and perhaps suffocates the piece. Such mild reservations side, however, Sprackland’s poetic skill is well illustrated throughout this pamphlet with eloquent and intriguing lines like: “Power cord as vapour trail./White smoke as cigarette smoke,/smoking as wedding dress pulled through water,/ smoke as blood in water.”

Martha Sprackland’s first pamphlet gives an enjoyable glimpse into her world and mind and shows that she is a poet with genuine talent and insight. I look forward to reading a full collection soon.

.

Peter Daniels on Brexit Day on the Balmoral Estate by Rory Waterman

.

Peter Daniels on Brexit Day on the Balmoral Estate by Rory Waterman

.

These are poems of place – of tourism mostly, but with politics and war often close, if only historically. In ‘Writ in Water’ a couple in Venice face that their relationship can’t survive as he has “spent the best of three years at Cap Nama, then Balad, / though you and I and she mustn’t know what he did there” at the torture camps of Iraq. ‘You’ and ‘I’ don’t otherwise feature in the poem: we are evidently the public world out there which knows something but not the full story, and I admit I feel a little out of touch myself with news and recent history, having had to Google those places. There was other information that poems didn’t supply: I’m not in favour of spoonfeeding, and Google is always with us, but it can seriously affect how a poem comes across, especially ‘Granattrichter mit Blumen (1924)’ after an etching by Otto Dix – it’s a First World War bomb crater and a powerful image when you see it, but as poems about pictures go this one did need the picture. “We know they’ve filled it all in” – or we do know when we know enough about it, this gap in assumed knowledge an unnecessary barrier despite the rest of the sentence’s perfect expression and tone: “that ninety ploughs / have dragged their fingers against his remembered earth.”

Sarajevo’s recent history is more known: in the first of the pair ‘Sarajevo Roses’, it is background to adolescent first love angst while “Bosnia took up the television, / as though to mock my suffering as well”; in the second we are tourists in the aftermath where remains of bullets and shells are for sale as pens and toy helicopters “that we catch ourselves thinking / crass, or (un)necessary”. I’m not sure how anyone is to read that bracket, and wish the poem either spelt out the complicated opposed feelings or didn’t attempt them. But apart from a few things like that, the poems are well put together. Larkin is behind many of them, in turns of phrase as well as mood – “Self-derision / thumped at me for days. It came in swells” (‘Sarajevo Roses I’ again). Larkin is also in subjects, with echoes of ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ – “as another couple stepped out, their business done –/ all clichés then, whatever lay in store” (‘The Brides of Castell de Belver’) – and of ‘An Arundel Tomb’ in ‘Ave Maria’, which closes with the opportunity to touch a statue of the infant Jesus “and sense love bursting fresh from a cold beige foot.”

Brexit as a theme is mostly absent but implied by poems being set outside Britain: in Europe (not necessarily EU) except for ‘Reunion’ in the USA, its time signalled because “signs saying Bernie have mostly been pulled now”, and Trump v. Clinton is on T.V. The scene is brought to us with clever economy, though I wonder why ‘Reunion’ when the people are strangers, and the ending “I wish this man well” has no grass, lawnmower or other rationale attached to the clear echo of Douglas Dunn’s Terry Street. In the title poem, the Balmoral Estate responds to Brexit with royal aloofness – “two deer, in stately deportment” who “do not know there is no stalking today. / They do not know there was stalking yesterday.” I Googled to check whether 24 June was significant in the deer hunting calendar, which it isn’t: the lack of significance is therefore significant but not obvious. I regret having these worries about information, because the poems display clarity and craft and bring us the sense of their occasions strongly without fuss.

London Grip reviews four recent poetry pamphlets from Rack Press

A poetry pamphlet is often a beautiful thing to hold as well as to read. Printed on delicately-ribbed cream pages inside a grey cover worthy of Farrow and Ball, Kathryn Gray’s Flowers is a good example.

The opening poem’s title, ‘The Meet-Cute’, sent me straight to Duck-Duck-Go for a definition; it turns out to be the term for a particular kind of romantic meeting on film or TV, and set me on track for a sequence of poems that refer to and riff off a range of cultural and counter-cultural texts from film, TV, comedy and pop music. Specifically located in time and place, this field of reference might prove daunting to anyone who hasn’t seen the films or heard the music (I had more homework to do in order to untangle the Ferris Bueller and Breakfast Club characters who inhabit two of the poems). But Gray knows how to use these references to illuminate themes of real longing and pain, a more profound coming-of-age. In the first stanza of ‘The Meet-Cute’, she describes how, in a scene from a romantic film,

and I’m won over immediately. Throughout the nine poems, the world of mass media provides landscapes in which Gray moves deftly between irony and painful honesty. No coincidence that cult comedian Bill Hicks features in the second poem, a kind of elegy; Gray writes of a powerful connection:

This small selection ranges quite widely and with great confidence in terms of form: each poem seems effortlessly fitted into the shape that suits it best. There are eight- and four-line stanzas made out of fluent, developed sentences; taut couplets and tercets; a prose poem; and more relaxed, sprawling lines that convey a conversational tone. There is a darkly witty poem, ‘I am the world’s last barman poet’ constructed around the names of (fictional?) cocktails: the Irish Car Bomb… The Four Horsemen.

I particularly like ‘Bournemouth’, addressed to “an imaginary friend”, the poet Rosemary Tonks (known in her reclusive final years as Mrs Lightband), in which the speaker describes a mind that “turns…/folds itself/over and over” like an “endless, sentient/serviette”. Internal and end rhyme and subtle rhythmic effects push the poem gently toward a marvellous conclusion where it is hard to discern whose tears “will be nothing new, while the stars– /our startlers– the stars impossibly accrue”.

In other ways accessible, these poems do rely on a specialised area of knowledge and in that sense, for this reader, they have at times a cryptic quality. The final poem is a good example: it reveals the origin of the pamphlet’s title– as surprising as many other facets of a sequence that combines pin-sharp intelligence with a touching vulnerability. I will leave the precise reference for readers to discover for themselves. The pamphlet comes to an end on the word ‘flowers’; it means something rather different from what you might expect.

.

Chris Kinsey makes poems that show nature vividly and often unexpectedly. She knows a lot about nature and wants to record the creatures, especially birds, and how they make impressions on her which she can interpret for the reader – sometimes briefly, a moment encapsulated like a haiku though longer: the nine lines of ‘Injured Angels’, which are whooper swans; the four five-line stanzas of ‘For a Friend Facing Surgery’, each a separate bird encounter, starting with “I send you the dipper, not genuflecting / to the rock, but bowing to appetite”. Animal behaviour is often described in terms like that one, not necessarily anthropomorphic but borrowing an image from the human world, like “swallows soar and flip, stropping / themselves on the clear sky” (‘For a Friend Facing Surgery’), or “I watched herons’ silent flamenco”(‘Muddy Fox’) – an image I find harder to appreciate, because unlike the stropping movement, the flamenco is more complex to imagine, with the added distancing of ‘silent’ so unlike the real life dancing.

On the whole I wish the imagery was kept simpler, as poems I otherwise like are weighed down with decorative embroidery, and words and images sometimes draw attention from the subject instead of illuminating it. It shouldn’t be impossible to use words like ‘azure’ or ‘cerulean’ – no word should be impossible – but they overbalance this:

Nothing in the church’s stained glass or heavenly ceiling compared with the flash of azure damselflies on clear leaded wings, or the cerulean lake’s mirrored clouds (Trompe l’oeil’)These are “things I missed as a child – I was too avid to see / and hadn’t learnt to hold my shadow off the water.” I feel the poet’s shadow is a little too much on the water of her poems, in the form of belief that the world is there to be made into poems whether it wants to be or not. That comes especially in ‘Busker’, where the violinist “conjures more than he knows”, as if the poet’s interpretation is of more importance than the music itself.

In some of the best poems, nature is participating in the relationship with other people: her mother as a girl gathering wimberries, as she also does (‘Wimberries’), or the title poem with its tone of displaced worry for the cycling companion setting off for chemotherapy while she cleans her Muddy Fox bike, in the hope of riding together next March. And the observations of nature are constantly showing us things we might not know about the world around us, so are worth reading for that.

.

Martha Sprackland’s short pamphlet, Glass As Broken Glass is her first and it shows her to be a poet of considerable creative powers, with astute diction and use of imagery, together with a tranquil repose in the sense of time and place. The pamphlet contains eight poems dealing with subjects ranging from a trip to a museum to a man who holds the record for surviving being hit by lightning. It is a shame that a short pamphlet does not allow particular themes and narratives to flourish or be nurtured to full development, and very occasionally the author can over use language to the slight detriment of the poem and her poetic voice.

The first poem “Snail” opens with the line “I caved him in with the heel of my shoe”; however, it seems, this leaves “the job half-done,” and there are anxious pangs of regret and remorse: Unless “ I bring my foot down hard again/ … I know with absolute certainty / that it will follow me where I go” This is a frank and honest poem taking on the sentimentality associated with love and death .

The second poem is about the poet’s visit to the Hunterian museum in Glasgow with its “ghostly archive”, whch includes “silver birch leaves in the moonlight, and the teeth / and textbook jaws and joints of elephants and antelope”. Images like “Black malignancies glued inside the ribcage like wasps’ nests,” succeed in conveying the eerie atmosphere of the museum.

Elsewhere the poet describes the No 38 bus “blaring like a drunk as it rolls away to town.” Having dropped her phone at a bus-stop, she stares at it on the ground, “both smashed and not-smashed” and reminding her of “the robin egg child-me found down at the rec”. Again the poet is at ease with her subject matter as she expresses the emotion behind the experience.

“Tricksters Shark and Selkie” opens with the lines “Shark won’t be fooled by the lure/in sealskin black towed behind the motorboat” and continues with some fine, articulate phrases like “the skyscraper stands of kelp/as back-alley and shadow” However, this was the one poem where arguably the poet is slightly too convoluted in her use of language and perhaps suffocates the piece. Such mild reservations side, however, Sprackland’s poetic skill is well illustrated throughout this pamphlet with eloquent and intriguing lines like: “Power cord as vapour trail./White smoke as cigarette smoke,/smoking as wedding dress pulled through water,/ smoke as blood in water.”

Martha Sprackland’s first pamphlet gives an enjoyable glimpse into her world and mind and shows that she is a poet with genuine talent and insight. I look forward to reading a full collection soon.

.

These are poems of place – of tourism mostly, but with politics and war often close, if only historically. In ‘Writ in Water’ a couple in Venice face that their relationship can’t survive as he has “spent the best of three years at Cap Nama, then Balad, / though you and I and she mustn’t know what he did there” at the torture camps of Iraq. ‘You’ and ‘I’ don’t otherwise feature in the poem: we are evidently the public world out there which knows something but not the full story, and I admit I feel a little out of touch myself with news and recent history, having had to Google those places. There was other information that poems didn’t supply: I’m not in favour of spoonfeeding, and Google is always with us, but it can seriously affect how a poem comes across, especially ‘Granattrichter mit Blumen (1924)’ after an etching by Otto Dix – it’s a First World War bomb crater and a powerful image when you see it, but as poems about pictures go this one did need the picture. “We know they’ve filled it all in” – or we do know when we know enough about it, this gap in assumed knowledge an unnecessary barrier despite the rest of the sentence’s perfect expression and tone: “that ninety ploughs / have dragged their fingers against his remembered earth.”

Sarajevo’s recent history is more known: in the first of the pair ‘Sarajevo Roses’, it is background to adolescent first love angst while “Bosnia took up the television, / as though to mock my suffering as well”; in the second we are tourists in the aftermath where remains of bullets and shells are for sale as pens and toy helicopters “that we catch ourselves thinking / crass, or (un)necessary”. I’m not sure how anyone is to read that bracket, and wish the poem either spelt out the complicated opposed feelings or didn’t attempt them. But apart from a few things like that, the poems are well put together. Larkin is behind many of them, in turns of phrase as well as mood – “Self-derision / thumped at me for days. It came in swells” (‘Sarajevo Roses I’ again). Larkin is also in subjects, with echoes of ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ – “as another couple stepped out, their business done –/ all clichés then, whatever lay in store” (‘The Brides of Castell de Belver’) – and of ‘An Arundel Tomb’ in ‘Ave Maria’, which closes with the opportunity to touch a statue of the infant Jesus “and sense love bursting fresh from a cold beige foot.”

Brexit as a theme is mostly absent but implied by poems being set outside Britain: in Europe (not necessarily EU) except for ‘Reunion’ in the USA, its time signalled because “signs saying Bernie have mostly been pulled now”, and Trump v. Clinton is on T.V. The scene is brought to us with clever economy, though I wonder why ‘Reunion’ when the people are strangers, and the ending “I wish this man well” has no grass, lawnmower or other rationale attached to the clear echo of Douglas Dunn’s Terry Street. In the title poem, the Balmoral Estate responds to Brexit with royal aloofness – “two deer, in stately deportment” who “do not know there is no stalking today. / They do not know there was stalking yesterday.” I Googled to check whether 24 June was significant in the deer hunting calendar, which it isn’t: the lack of significance is therefore significant but not obvious. I regret having these worries about information, because the poems display clarity and craft and bring us the sense of their occasions strongly without fuss.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, Michael Bartholomew-Biggs, poetry