Ruth Valentine considers the balance between politics and poetics in Alan Morrison’s new collection

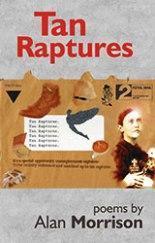

Tan Raptures

Alan Morrison

Smokestack Books, 2017

ISBN: 978-0-9955635-0-6

£8.99

Tan Raptures

Alan Morrison

Smokestack Books, 2017

ISBN: 978-0-9955635-0-6

£8.99

There is a tradition of overtly political poetry In Britain, but we mainly overlook it, or cast it, like its overseas equivalent, as fine for then or there, but hardly suitable for us, now: a bit excessive, a tad embarrassing, lacking in sweetness or irony or allusion. Alan Morrison has no such qualms:

Sanguine Lagarde, phlegmatic permatanned Madame de

Austérité, hostess of the IMF, beguiling while reclining

On her Louis XVI chaise-longue,

‘Greeks Bearing Rifts, 5’

Morrison is a socialist, alert, as that extract suggests, to the assaults of global capitalism, both large- and small-scale, and to the history and geography of popular revolt. The women’s strike at Bryant and May is probably not on the national curriculum, but Morrison has no doubt of its significance.

Spark up your Lucifers and spare a thought

For the phossy-jawed match-girls who struck a match

Back in 1888, which would conflagrate and catch

Across the sulphur-clouded working classes

‘The Moving Rainbow,1’

Phossy jaw was the catastrophic, disfiguring result of working with white phosphorus. Morrison is typically knowledgeable here, in both the causes and impact of the strike, and the lives of the mainly Irish women involved. At best, as here, his factual knowledge and his empathic anger form the poem, creating the imagery and enlivening the black verse with rhythm and the occasional rhyme. Sometimes the verse is more formal, as in ‘Ash Friday,’ his response to the fire at the anarchist Freedom Bookshop in the East End, where the metre and the repeated o-rhymes insist like a drum-beat or a protest song on the significance of the event:

The lights are out in Whitechapel but brick-lit beacons glow –

When torches burn for ‘freedom’, the books are first to go,

They catch at Fahrenheit Four Five One (as all fascists know),

Insistence and erudition are not only the strength of this type of verse; they are also its potential pitfalls. How do you convey a history your readers have probably forgotten, a lesson they may not have grasped, without becoming the bloke in the corner of the bar, or the Ancient Mariner? There are several possible answers: imagery, detail, form; those elements that distinguish poetry from prose. Morrison is not a formalist – the majority of the poems are solid blocks of blank verse, a touch intimidating on the page – but he can ring the changes. Take ‘Digger Hinges,’ which celebrates the Runnymede Diggers of 2012, who took their name and their principles – access to the land – from their seventeenth-century forebears:

Offspring of empty purse-strings, a borrowed rainbow army

Simmering a common broth from beetroots, sprouts and poetry,

Here the form is rhymed triplets, the same e-rhyme throughout the twenty-one stanzas.

Imagery is Morrison’s strength. In the title sequence – Tan Raptures are the results of the ominous brown envelopes from what he calls the Dee Double-u Pee – we have “That August, attitudes hardened like tarred arteries, and austerity/Throttled the wilting trees”, to set the scene for the political demonisations and bureaucratic cruelties he enumerates. Images like this energise the poems, and give a context to the sometimes obsessive detail. He wants us to understand the horror of the privatised system of assessment for disability benefits, that

. …countless went prematurely, penalised into post-

. Sentience, 2,380 within six weeks of being declared ‘fit

. For work’ by Atos in the space of just three years…

‘Post-Rapture: A Compromise Too Far’

The facts are horrific: but is this poetry or journalism? Both perhaps. I’m still not sure. These are breathless poems, often short on punctuation; passionate, wide-ranging, unashamedly fighting for the disenfranchised, in a time when the fight could hardly be more urgent. Perhaps it doesn’t matter how you classify them. I have the sense that they might convince more of the unconvinced – or rally more of the converted – if they were more formed, more selective; but I’m equally sure that they would no longer be the utterance of this extraordinary, intense, much-needed poet.

Ruth Valentine considers the balance between politics and poetics in Alan Morrison’s new collection

There is a tradition of overtly political poetry In Britain, but we mainly overlook it, or cast it, like its overseas equivalent, as fine for then or there, but hardly suitable for us, now: a bit excessive, a tad embarrassing, lacking in sweetness or irony or allusion. Alan Morrison has no such qualms:

Morrison is a socialist, alert, as that extract suggests, to the assaults of global capitalism, both large- and small-scale, and to the history and geography of popular revolt. The women’s strike at Bryant and May is probably not on the national curriculum, but Morrison has no doubt of its significance.

Phossy jaw was the catastrophic, disfiguring result of working with white phosphorus. Morrison is typically knowledgeable here, in both the causes and impact of the strike, and the lives of the mainly Irish women involved. At best, as here, his factual knowledge and his empathic anger form the poem, creating the imagery and enlivening the black verse with rhythm and the occasional rhyme. Sometimes the verse is more formal, as in ‘Ash Friday,’ his response to the fire at the anarchist Freedom Bookshop in the East End, where the metre and the repeated o-rhymes insist like a drum-beat or a protest song on the significance of the event:

Insistence and erudition are not only the strength of this type of verse; they are also its potential pitfalls. How do you convey a history your readers have probably forgotten, a lesson they may not have grasped, without becoming the bloke in the corner of the bar, or the Ancient Mariner? There are several possible answers: imagery, detail, form; those elements that distinguish poetry from prose. Morrison is not a formalist – the majority of the poems are solid blocks of blank verse, a touch intimidating on the page – but he can ring the changes. Take ‘Digger Hinges,’ which celebrates the Runnymede Diggers of 2012, who took their name and their principles – access to the land – from their seventeenth-century forebears:

Here the form is rhymed triplets, the same e-rhyme throughout the twenty-one stanzas.

Imagery is Morrison’s strength. In the title sequence – Tan Raptures are the results of the ominous brown envelopes from what he calls the Dee Double-u Pee – we have “That August, attitudes hardened like tarred arteries, and austerity/Throttled the wilting trees”, to set the scene for the political demonisations and bureaucratic cruelties he enumerates. Images like this energise the poems, and give a context to the sometimes obsessive detail. He wants us to understand the horror of the privatised system of assessment for disability benefits, that

The facts are horrific: but is this poetry or journalism? Both perhaps. I’m still not sure. These are breathless poems, often short on punctuation; passionate, wide-ranging, unashamedly fighting for the disenfranchised, in a time when the fight could hardly be more urgent. Perhaps it doesn’t matter how you classify them. I have the sense that they might convince more of the unconvinced – or rally more of the converted – if they were more formed, more selective; but I’m equally sure that they would no longer be the utterance of this extraordinary, intense, much-needed poet.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, politics, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, poetry, politics, Ruth Valentine