A spiritual autobiography by Murray Bodo turns out to be an unexpectedly down-to-earth story

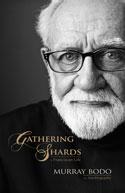

Gathering Shards, A Franciscan Life

Murray Bodo

Tau Publishing

ISBN 978-1-61956-484-8

$24.95 (hard cover) $16.95 (paperback)

Gathering Shards, A Franciscan Life

Murray Bodo

Tau Publishing

ISBN 978-1-61956-484-8

$24.95 (hard cover) $16.95 (paperback)

Gathering Shards is the autobiography of the Franciscan friar and priest Murray Bodo. That sentence alone might cause many people to suppose that the book could only be of interest to “seriously religious” readers. There are a number of reasons why such a supposition would be inaccurate. These reasons – not necessarily in order of persuasiveness – include the fact (pretty obvious from page one) that Bodo is a very warm and “ordinary” human being who makes clear that (contrary to some secular prejudices) the religious life does not consist entirely of serene certainty and calm superiority. Furthermore, since Bodo has spent much of his life as a teacher and scholar of literature (and is also a widely published author and poet) the book is written in pleasingly lucid prose and with a sense of how to tell a good story. And because his life in one of the poorer areas of Cincinnati has not been the enclosed monastic existence some might expect, he has many stories worth telling. And furthermore again, Bodo has chosen to interpolate and illuminate the narrative with a selection of his own poems (some taken from collections Wounded Angels, Something Like Jasmine and Autumn Train which have been reviewed on London Grip https://londongrip.co.uk/2011/09/poetry-reviews-2011-larger-font/#book2,

https://londongrip.co.uk/2012/11/poetry-review-autumn-2012-six-overseas-poets/

https://londongrip.co.uk/2015/07/london-grip-poetry-review-mccarthy-bodo/.)

Murray Bodo was born (as Louis Bodo – his name was changed at his ordination) to Italian parents living in the rural south-west of the USA. He gives us lively and revealing glimpses of his family background and of childhood events and adventures which he now sees as being pointers to his eventual vocation to the Franciscan life. He also presents loving and vivid portraits of his parents and faces up to the sense of loss they felt when he left home at fourteen to go to the seminary and they knew that in future he would only be with them for a few weeks in each year. In ‘Polly’ – a poem written about his mother after her death – he owns up to things he only discovered years afterwards:

You had to deal with Dad, I

blind to your quiet fight to

keep him from telling me how

he’d caved and fled to the hills.

Missing Polly, Bodo and his father seek consolation in the same hills that the father took refuge in after the ‘loss’ of his son:

When his mother dies the son asks

the father, can they go fishing once more.

They cast bait and know she prayed

they’d fish and talk as before.

[‘A Hard Floor Ghazal’]

This kind of sensitivity to feelings – his own and other people’s – is evident throughout the book and informs some searching reflections on faith and the doubts and difficulties attendant on living a religious life. In prose, Bodo is particularly honest about his struggle as a young man to learn how to avoid trampling on all tender feelings when seeking to reconcile the celibate life with a range of human friendships. He tackles this matter more obliquely in a poem ‘While Visiting the Home of Henry James in Rye’ in which he reflects

with a rueful smile that

things recur and we can bless

what we dismissed, like the

childhood dog we outgrew

or in my case “gave up” for

a pseudo God who disappeared

A few lines later he tells us

I did not understand , lost

my innocence to a false

repressive religion that

frowned on petting and cuddling

animals I now embrace to

re-find the innocent God

of my childhood

Henry James is just one of many literary figures who are mentioned as Bodo explores ways in which his love of literature has informed his spiritual life and his understanding of scripture. Two writers who receive particular attention are Denise Levertov and Herbert Lomas with whom Bodo shared deep friendships over many years. By drawing on correspondence and diaries, Bodo is able to present a very personal portrait of each of these fine poets – so much so that one might almost say Gathering Shards offers three biographies for the price of one! An especial delight is the section where we eavesdrop on Levertov workshopping a first draft of one of Bodo’s poems. And an intriguing piece of information (that surely deserves further investigation) is that – in addition to his many books of poetry – Lomas wrote a critique of capitalism entitled Who Needs Money? long before the 2008 financial crash and subsequent flood of volumes of monetary hand-wringing.

Murray Bodo has spent around half his life studying and writing about St Francis and leading summer pilgrimages in and around Assisi. In this book he briefly relates the fairly familiar story of how Francis turned his back on a comfortable life in a well-to-do family and chose instead a life of poverty and service. Unusually, however, Bodo (drawing perhaps on his own experience of leaving home) spares thoughts for Francis’s parents and includes two tender poems speculating about their feelings of loss. Coming up to date, he shares interesting reflections about how the life of a present-day Franciscan compares with the pattern set down by Francis and his followers in the 13th century; and he gives us vivid impressions of Assisi and its surroundings where he has been leading people in the footsteps of St Francis every summer since 1976. He also writes at some length about his friendship with an English priest, Father Francis Harpin, who lived in Assisi for the last fifteen or so years of his life. Bodo is able to tell something of Father Harpin’s little-known but intriguing story by quoting from his unpublished memoir My Vision Splendid. (Hence we may increase our previous estimate and say that Gathering Shards offers something like four-and-a-half biographies for the price of one – since the life story of St Francis is treated only briefly!)

When the reader comes upon several pages of photographs at around page 250 (s)he might conclude that the story is finished. But there are in fact another hundred or so pages of material. These ‘bonus tracks’ (as we might be tempted to call them) include reflections that resemble sermons or theological essays alongside more light-hearted ‘life lessons’ on subjects such as growing old. On this latter topic, Bodo is grateful to report that he is still living an active life in his late seventies and he attributes this to his creative us of imagination: like Walter Mitty, when he is travelling, I invent a story of me on a train. And wouldn’t people be surprised if they knew a detective-author-actor-saint, or reprobate, was sitting beside them? In this spirit, he sums up his attitude to growing old as follows: By living what the imagination creates we are expanding possibilities even as the body tries to age faster than it needs to.

There are many more elements in Bodo’s story than have been mentioned here. Indeed the concluding pages might be said to offer rather too many shards to be gathered all at once; and the last part of the book may be for dipping into rather than for reading as a narrative like the preceding chapters. But taken as whole the book reveals a life that has contained much joy and satisfaction and whose difficult parts have been approached with a patience and confidence that never spills over into self-satisfaction or arrogance. One final quote seems to sum up Bodo’s characteristic and attractive mixture of resolve and humility: True wisdom makes us do what others consider foolish, like privileging the poor and the despised, and finding God where we thought we were bringing God.

.

. Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

A spiritual autobiography by Murray Bodo turns out to be an unexpectedly down-to-earth story

Gathering Shards is the autobiography of the Franciscan friar and priest Murray Bodo. That sentence alone might cause many people to suppose that the book could only be of interest to “seriously religious” readers. There are a number of reasons why such a supposition would be inaccurate. These reasons – not necessarily in order of persuasiveness – include the fact (pretty obvious from page one) that Bodo is a very warm and “ordinary” human being who makes clear that (contrary to some secular prejudices) the religious life does not consist entirely of serene certainty and calm superiority. Furthermore, since Bodo has spent much of his life as a teacher and scholar of literature (and is also a widely published author and poet) the book is written in pleasingly lucid prose and with a sense of how to tell a good story. And because his life in one of the poorer areas of Cincinnati has not been the enclosed monastic existence some might expect, he has many stories worth telling. And furthermore again, Bodo has chosen to interpolate and illuminate the narrative with a selection of his own poems (some taken from collections Wounded Angels, Something Like Jasmine and Autumn Train which have been reviewed on London Grip https://londongrip.co.uk/2011/09/poetry-reviews-2011-larger-font/#book2,

https://londongrip.co.uk/2012/11/poetry-review-autumn-2012-six-overseas-poets/

https://londongrip.co.uk/2015/07/london-grip-poetry-review-mccarthy-bodo/.)

Murray Bodo was born (as Louis Bodo – his name was changed at his ordination) to Italian parents living in the rural south-west of the USA. He gives us lively and revealing glimpses of his family background and of childhood events and adventures which he now sees as being pointers to his eventual vocation to the Franciscan life. He also presents loving and vivid portraits of his parents and faces up to the sense of loss they felt when he left home at fourteen to go to the seminary and they knew that in future he would only be with them for a few weeks in each year. In ‘Polly’ – a poem written about his mother after her death – he owns up to things he only discovered years afterwards:

Missing Polly, Bodo and his father seek consolation in the same hills that the father took refuge in after the ‘loss’ of his son:

When his mother dies the son asks the father, can they go fishing once more. They cast bait and know she prayed they’d fish and talk as before. [‘A Hard Floor Ghazal’]This kind of sensitivity to feelings – his own and other people’s – is evident throughout the book and informs some searching reflections on faith and the doubts and difficulties attendant on living a religious life. In prose, Bodo is particularly honest about his struggle as a young man to learn how to avoid trampling on all tender feelings when seeking to reconcile the celibate life with a range of human friendships. He tackles this matter more obliquely in a poem ‘While Visiting the Home of Henry James in Rye’ in which he reflects

A few lines later he tells us

Henry James is just one of many literary figures who are mentioned as Bodo explores ways in which his love of literature has informed his spiritual life and his understanding of scripture. Two writers who receive particular attention are Denise Levertov and Herbert Lomas with whom Bodo shared deep friendships over many years. By drawing on correspondence and diaries, Bodo is able to present a very personal portrait of each of these fine poets – so much so that one might almost say Gathering Shards offers three biographies for the price of one! An especial delight is the section where we eavesdrop on Levertov workshopping a first draft of one of Bodo’s poems. And an intriguing piece of information (that surely deserves further investigation) is that – in addition to his many books of poetry – Lomas wrote a critique of capitalism entitled Who Needs Money? long before the 2008 financial crash and subsequent flood of volumes of monetary hand-wringing.

Murray Bodo has spent around half his life studying and writing about St Francis and leading summer pilgrimages in and around Assisi. In this book he briefly relates the fairly familiar story of how Francis turned his back on a comfortable life in a well-to-do family and chose instead a life of poverty and service. Unusually, however, Bodo (drawing perhaps on his own experience of leaving home) spares thoughts for Francis’s parents and includes two tender poems speculating about their feelings of loss. Coming up to date, he shares interesting reflections about how the life of a present-day Franciscan compares with the pattern set down by Francis and his followers in the 13th century; and he gives us vivid impressions of Assisi and its surroundings where he has been leading people in the footsteps of St Francis every summer since 1976. He also writes at some length about his friendship with an English priest, Father Francis Harpin, who lived in Assisi for the last fifteen or so years of his life. Bodo is able to tell something of Father Harpin’s little-known but intriguing story by quoting from his unpublished memoir My Vision Splendid. (Hence we may increase our previous estimate and say that Gathering Shards offers something like four-and-a-half biographies for the price of one – since the life story of St Francis is treated only briefly!)

When the reader comes upon several pages of photographs at around page 250 (s)he might conclude that the story is finished. But there are in fact another hundred or so pages of material. These ‘bonus tracks’ (as we might be tempted to call them) include reflections that resemble sermons or theological essays alongside more light-hearted ‘life lessons’ on subjects such as growing old. On this latter topic, Bodo is grateful to report that he is still living an active life in his late seventies and he attributes this to his creative us of imagination: like Walter Mitty, when he is travelling, I invent a story of me on a train. And wouldn’t people be surprised if they knew a detective-author-actor-saint, or reprobate, was sitting beside them? In this spirit, he sums up his attitude to growing old as follows: By living what the imagination creates we are expanding possibilities even as the body tries to age faster than it needs to.

There are many more elements in Bodo’s story than have been mentioned here. Indeed the concluding pages might be said to offer rather too many shards to be gathered all at once; and the last part of the book may be for dipping into rather than for reading as a narrative like the preceding chapters. But taken as whole the book reveals a life that has contained much joy and satisfaction and whose difficult parts have been approached with a patience and confidence that never spills over into self-satisfaction or arrogance. One final quote seems to sum up Bodo’s characteristic and attractive mixture of resolve and humility: True wisdom makes us do what others consider foolish, like privileging the poor and the despised, and finding God where we thought we were bringing God.

.

. Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • authors, books, religion, year 2016 0 • Tags: authors, books, Michael Bartholomew-Biggs