Writing the ‘Big C’: Brian Docherty reviews a new collection from Wendy French

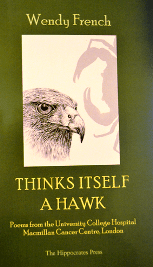

Thinks Itself a Hawk

London, The Hippocrates Press, 2016

ISBN 978-0-957-2571-7-7

£10

Thinks Itself a Hawk

London, The Hippocrates Press, 2016

ISBN 978-0-957-2571-7-7

£10

This handsome, well-produced book, from a press which is the imprint of the Hippocrates Initiative for poetry and medicine, is one of the several outcomes of a residency Wendy French held at the University College Hospital Macmillan Centre for Cancer Research in London. This is her third full collection, and it contains occasional poems in the proper sense – i.e. not strictly speaking in the main flow of her work (although as a Lapidus member, she has a long-standing personal and professional interest in the uses of writing in therapeutic contexts). Her title is related to Helen Macdonald’s book H is for Hawk, and the half title page features this:

C is for Cancer

thinks itself a hawk

takes on its sport

to survive grief

exists to kill

The notion of cancer as a powerful, impersonal force, which has its own existence in the world at large, and not just in the bodies and lives of individual sufferers, informs the poems here, and is well articulated from a variety of perspectives. The book is in two parts: the first is a range of responses to the reality of living with, and dealing with, cancer; while the second is a sequence using the words of a named cancer patient, with that person’s co-operation and permission. This collaboration allows a more closely sustained response to the subject matter, and features a separate preface which gives the reader some details of this individual’s life and personal history.

Anyone who imagines that cancer, especially on a mass scale, is a relatively recent phenomenon, or that leprosy was an ancestor of cancer, might like to know that (according to the Campaign for the Prevention of Cancer) there are 200 types of cancer, and that the American Cancer Society states that cancer was known by at least 3,000 BC, and that the Edwin Smith Papyrus states ‘There is no known cure’. Fortunately, French’s book is not weighed down with that sort of detail; you can google it yourself.

A variety of perspectives are deployed, using mainstream free verse with relatively little use of traditional apparatus; perhaps French felt that using more formal structures would have offered the wrong sort of constraints, and distracted from letting the subject matter speak for itself. (Another approach to writing about or around cancer can be found in Jo Shapcott’s Of Mutability, (Faber & Faber, 2010) well reviewed by Kate Kellaway in the Guardian.) However, unless French is the ‘Mrs. Wendy Rowena‘ addressed by the Spanish nurse in ‘Mammogram’ we cannot assume anything directly personal in the poems here. One formal strategy French does deploy, as in some of her earlier work, is the use of Sappho’s fragments, in Anne Carson’s versions, as epigraphs to her poems. Precisely because all we have are fragments, often only a line or two, or even broken pieces, Sappho provides French with a kickstart for her own versions of Zipora’s life, from which her own poems follow. These fragmentary yet resonant words can, perhaps, be seen as emblematic of the nature of modern experience, and like Cancer, a synecdoche for a person’s whole life, when Cancer starts out as a small part of the body, yet comes to dominate or represent the whole life.

The book opens with ‘Cancer’s Daily Walk’ – which introduces the notion that cancer can go anywhere, is ubiquitous, and iniquitous – and is followed by ‘Fugitive Colours’, and ‘Colour’ which concludes with bile in the bowl. We meet ‘The Concierge’, the person by whom everyone entering the Cancer Centre’s Huntley Street premises is welcomed. This leads into ‘Today’s Appointmen’ which deals with the mundane reality of treatment for breast cancer, involving among other things, a great deal of waiting about. Waiting in corridors or lobbies is a feature of several poems, from the perspective of sufferers, relatives or carers, and also in ‘Wheelchairs Waiting‘ the wheelchairs everyone in as hospital sees or uses. ‘Cancer’s Daily Crawl‘ picks up on the theme introduced in the opening poem, that cancer can go anywhere, and references the astrological trope of the Crab, and cancer as mobile, persistent and aggressive. ‘This Girl’ gives us a portrait of a girl old enough to have a lover, and not therefore a child, and tells us Even now the girl is beautiful.

The book moves on to another portrait, ‘In the Wood’ where a woman is imprisoned by tubes & drips, but can see a mural of bluebells on the wall, and wants to be there; the poem ends

She sees it plainly as she sits in the wood

and she doesn’t want to find a way through.

Readers are left to decide for themselves what is meant here, and whether we are invited to recall Dante’s ‘selva oscura‘. We are also introduced, in ‘The Tower‘ to one of Huntley Street’s scarier departments, where nuclear medicine is deployed. That’s when you know it’s serious. After a brief walk from say, Goodge Street station, and learning a new vocabulary, we are back in the children’s ward or clinic, where

In came the doctor, in came the nurse,

in came the lady with the alligator purse . . .

This could easily be Michael Rosen or Matthew Sweeney, but may have come from a writing workshop or therapy session involving younger sufferers. It shows, perhaps, a child’s eye view of cancer as banal yet threatening, a la Punch & Judy; but it also reminds us that the alligator, a top predator in its own environment, has been defeated by human agency, and reduced to a fashion item. However, ‘Cancer Speaks of Painting a Garden’ gives another child’s perspective: Shit, shit and more of it. The final poem in this first section, with its wonderful title, ‘We Are Made from Stars’, perhaps referencing Joni Mitchell’s lines from ‘Woodstock’, ‘we are stardust/we are golden’, introduces us to a sculpture, The Star. This, as the note to the poem tells us, was conceived, sculpted and donated by Roger, a patient. Let us hope that Roger survived to make more sculpture.

Section two of the book, ‘Zipora’ narrows and deepens the focus to the treatment of one person, Zipora Proctor. It is clear that French worked closely with Zipora, who, as the preface notes, ‘wanted her story told and her real name used’. There are two contrasted sorts of writing in this section: one is poems by French, the other is unsent letters from Zipora to the mother who died in childbirth. ‘Letter to Mama‘ reads in part,

Zipora writes to her mother every night. the letter is never

sent. She questions the relationship she never knew. The

following words are her words.

One letter goes like this:

Dear Mama,

It’s only now that I can appreciate all that you did for me -

dying at my birth you’d stayed alive to feel me kick and grow

inside you. Now my cancer’s grown like yours, destroys me

too. Forgive me, Mama, for all the times that I’ve forgotten

you. not called you by name.

But that’s not right, and starts again.

Zipora’s letters, in italics and justified, form an effective counterpoint to the poems about life in a kibbutz, such as ‘Haifa Kibbutz’ where French give the reader parts of a life, specifically a new life after the Holocaust. The poems opens

it was your choice to take yourself there,

abandon others for a profound hope

while ‘Rules of the Kibbutz’ gives us chapter & verse of everyday life as a kibbutzim. ‘Leaving the Kibbutz’ informs the reader that Zipora left after hearing her mother’s voice, and concludes

Everyone’s a stranger in the end.

It’s only in imagination we are friends.

In later poems, we get glimpses of a later life, including the compulsory call-up to the Israeli Army. In ‘Falafel’ the reader learns that

You wrote for This World, a sympathiser

for the Palestinians.

but life was flattened like your stomach.

What a choice that must have been. ‘In the Name of Peace’ details one of the many incidents that occurred then, and shows the difficulty of the position Zipora found herself in. Other poems use images of flowers, mountains, and sea effectively. The later poems in this sequence move towards a present of yet more death and uncertainty, this time Zipora’s approaching mortality. The penultimate piece is titled ‘Taxi ride from Arnos Grove to North Finchley Crematorium’ while in ‘For Zipora’, given that the last line is italicised, she appears to have the last word:

What I do is me: for that I came

although this is from Gerard Manley Hopkins’ untitled poem starting ‘As kingfishers catch fire, dragons draw flame;’. How fitting that a profoundly religious poet, at odds with aspects of that religious tradition, who spent his life and energies working with the poor and dispossessed, and who died early, should be given the last word.

Writing the ‘Big C’: Brian Docherty reviews a new collection from Wendy French

This handsome, well-produced book, from a press which is the imprint of the Hippocrates Initiative for poetry and medicine, is one of the several outcomes of a residency Wendy French held at the University College Hospital Macmillan Centre for Cancer Research in London. This is her third full collection, and it contains occasional poems in the proper sense – i.e. not strictly speaking in the main flow of her work (although as a Lapidus member, she has a long-standing personal and professional interest in the uses of writing in therapeutic contexts). Her title is related to Helen Macdonald’s book H is for Hawk, and the half title page features this:

C is for Cancer thinks itself a hawk takes on its sport to survive grief exists to killThe notion of cancer as a powerful, impersonal force, which has its own existence in the world at large, and not just in the bodies and lives of individual sufferers, informs the poems here, and is well articulated from a variety of perspectives. The book is in two parts: the first is a range of responses to the reality of living with, and dealing with, cancer; while the second is a sequence using the words of a named cancer patient, with that person’s co-operation and permission. This collaboration allows a more closely sustained response to the subject matter, and features a separate preface which gives the reader some details of this individual’s life and personal history.

Anyone who imagines that cancer, especially on a mass scale, is a relatively recent phenomenon, or that leprosy was an ancestor of cancer, might like to know that (according to the Campaign for the Prevention of Cancer) there are 200 types of cancer, and that the American Cancer Society states that cancer was known by at least 3,000 BC, and that the Edwin Smith Papyrus states ‘There is no known cure’. Fortunately, French’s book is not weighed down with that sort of detail; you can google it yourself.

A variety of perspectives are deployed, using mainstream free verse with relatively little use of traditional apparatus; perhaps French felt that using more formal structures would have offered the wrong sort of constraints, and distracted from letting the subject matter speak for itself. (Another approach to writing about or around cancer can be found in Jo Shapcott’s Of Mutability, (Faber & Faber, 2010) well reviewed by Kate Kellaway in the Guardian.) However, unless French is the ‘Mrs. Wendy Rowena‘ addressed by the Spanish nurse in ‘Mammogram’ we cannot assume anything directly personal in the poems here. One formal strategy French does deploy, as in some of her earlier work, is the use of Sappho’s fragments, in Anne Carson’s versions, as epigraphs to her poems. Precisely because all we have are fragments, often only a line or two, or even broken pieces, Sappho provides French with a kickstart for her own versions of Zipora’s life, from which her own poems follow. These fragmentary yet resonant words can, perhaps, be seen as emblematic of the nature of modern experience, and like Cancer, a synecdoche for a person’s whole life, when Cancer starts out as a small part of the body, yet comes to dominate or represent the whole life.

The book opens with ‘Cancer’s Daily Walk’ – which introduces the notion that cancer can go anywhere, is ubiquitous, and iniquitous – and is followed by ‘Fugitive Colours’, and ‘Colour’ which concludes with bile in the bowl. We meet ‘The Concierge’, the person by whom everyone entering the Cancer Centre’s Huntley Street premises is welcomed. This leads into ‘Today’s Appointmen’ which deals with the mundane reality of treatment for breast cancer, involving among other things, a great deal of waiting about. Waiting in corridors or lobbies is a feature of several poems, from the perspective of sufferers, relatives or carers, and also in ‘Wheelchairs Waiting‘ the wheelchairs everyone in as hospital sees or uses. ‘Cancer’s Daily Crawl‘ picks up on the theme introduced in the opening poem, that cancer can go anywhere, and references the astrological trope of the Crab, and cancer as mobile, persistent and aggressive. ‘This Girl’ gives us a portrait of a girl old enough to have a lover, and not therefore a child, and tells us Even now the girl is beautiful.

The book moves on to another portrait, ‘In the Wood’ where a woman is imprisoned by tubes & drips, but can see a mural of bluebells on the wall, and wants to be there; the poem ends

She sees it plainly as she sits in the wood and she doesn’t want to find a way through.Readers are left to decide for themselves what is meant here, and whether we are invited to recall Dante’s ‘selva oscura‘. We are also introduced, in ‘The Tower‘ to one of Huntley Street’s scarier departments, where nuclear medicine is deployed. That’s when you know it’s serious. After a brief walk from say, Goodge Street station, and learning a new vocabulary, we are back in the children’s ward or clinic, where

In came the doctor, in came the nurse, in came the lady with the alligator purse . . .This could easily be Michael Rosen or Matthew Sweeney, but may have come from a writing workshop or therapy session involving younger sufferers. It shows, perhaps, a child’s eye view of cancer as banal yet threatening, a la Punch & Judy; but it also reminds us that the alligator, a top predator in its own environment, has been defeated by human agency, and reduced to a fashion item. However, ‘Cancer Speaks of Painting a Garden’ gives another child’s perspective: Shit, shit and more of it. The final poem in this first section, with its wonderful title, ‘We Are Made from Stars’, perhaps referencing Joni Mitchell’s lines from ‘Woodstock’, ‘we are stardust/we are golden’, introduces us to a sculpture, The Star. This, as the note to the poem tells us, was conceived, sculpted and donated by Roger, a patient. Let us hope that Roger survived to make more sculpture.

Section two of the book, ‘Zipora’ narrows and deepens the focus to the treatment of one person, Zipora Proctor. It is clear that French worked closely with Zipora, who, as the preface notes, ‘wanted her story told and her real name used’. There are two contrasted sorts of writing in this section: one is poems by French, the other is unsent letters from Zipora to the mother who died in childbirth. ‘Letter to Mama‘ reads in part,

Zipora writes to her mother every night. the letter is never sent. She questions the relationship she never knew. The following words are her words. One letter goes like this: Dear Mama, It’s only now that I can appreciate all that you did for me - dying at my birth you’d stayed alive to feel me kick and grow inside you. Now my cancer’s grown like yours, destroys me too. Forgive me, Mama, for all the times that I’ve forgotten you. not called you by name. But that’s not right, and starts again.Zipora’s letters, in italics and justified, form an effective counterpoint to the poems about life in a kibbutz, such as ‘Haifa Kibbutz’ where French give the reader parts of a life, specifically a new life after the Holocaust. The poems opens

it was your choice to take yourself there, abandon others for a profound hopewhile ‘Rules of the Kibbutz’ gives us chapter & verse of everyday life as a kibbutzim. ‘Leaving the Kibbutz’ informs the reader that Zipora left after hearing her mother’s voice, and concludes

Everyone’s a stranger in the end. It’s only in imagination we are friends.In later poems, we get glimpses of a later life, including the compulsory call-up to the Israeli Army. In ‘Falafel’ the reader learns that

You wrote for This World, a sympathiser for the Palestinians. but life was flattened like your stomach.What a choice that must have been. ‘In the Name of Peace’ details one of the many incidents that occurred then, and shows the difficulty of the position Zipora found herself in. Other poems use images of flowers, mountains, and sea effectively. The later poems in this sequence move towards a present of yet more death and uncertainty, this time Zipora’s approaching mortality. The penultimate piece is titled ‘Taxi ride from Arnos Grove to North Finchley Crematorium’ while in ‘For Zipora’, given that the last line is italicised, she appears to have the last word:

although this is from Gerard Manley Hopkins’ untitled poem starting ‘As kingfishers catch fire, dragons draw flame;’. How fitting that a profoundly religious poet, at odds with aspects of that religious tradition, who spent his life and energies working with the poor and dispossessed, and who died early, should be given the last word.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2016 0 • Tags: Brian Docherty, poetry