Jay Bernard’s collection tells an ancient story in which Emma Lee finds some modern resonances

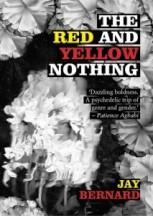

The Red and Yellow Nothing

Jay Bernard

Ink Sweat and Tears Press www.inksweattears.co.uk

ISBN 9780992725310

34pp £7.50

The Red and Yellow Nothing

Jay Bernard

Ink Sweat and Tears Press www.inksweattears.co.uk

ISBN 9780992725310

34pp £7.50

Winner of the sixth Cafe Writers Commission judged by Kate Birch, Chris Gribble and Helen Ivory, The Red and Yellow Nothing explores Sir Morien’s search for his father, Sir Agloval, a knight of King Arthur’s Round Table. It’s loosely a prequel to Morien: A Metrical Romance Rendered into English from the Middle Dutch, translated by Jessie Laidlay Weston (1901). Morien travels from Moorish lands to England to start his quest to find his father, in a sequence split into 13 parts, each starting with a stage direction. In II, the introduction suggests maybe we can empathise with the frustration one feels when the local people take one look at you, then hurry away from you before you’ve finished your sentence. Here, Morien asks a bard:

I'll fight you. Why don't you come out and face me and

fight me and tell me what you know? I've been riding since

I don't know when, now I don't know where,

why don't you come and face me. Everyone says

'I know not good knight where your father dwells.'

Naturally someone who’s trained as a knight since childhood would instinctively and as a reflex turn to his sword. The bard sings a story of a knight setting out on a quest but cannot answer Morien’s questions directly, giving rise to frustration. Readers don’t know who the everyone referred to is. Are they unarmed commoners wary of a knight’s sword? Are they being truthful about not knowing where Sir Agloval is? Do they refuse to answer because they are naturally suspicious of a stranger or because of some other prejudice? In not spelling out that Morien is black, Jay Bernard allows the readers to explore ideas around racial prejudice without directly being told this is the issue.

In III, Morien joins a competition where the prize is a kiss from a black lady; but he loses to a wild man who turns out to be a king. And as he kisses the black woman, the other men form a line, they pressed their mouths against the woman’s ass, laughing. The woman is revealed to be white.

How white is another thing. If the colour

was smell, then the maid was grey. Tallow

fish-oil and potash; saddle-seat; monthly blood

in dusty streaks along the base and up the crease.

As Morien pressed his nose into the fine clothes

and finer stench, he caught a woman in the corner

of his eye: she was dressed in red and yellow, sat

silent in the crowd, mouth and lips full and pursed,

both cheeks shining black like whorls of wood.

The richness of detail, particularly of smell, is apt. By showing, the poet doesn’t need to remind readers these are historical times. Morien loses the woman wearing red and yellow in the crowd and realises she was a figment of his imagination, an ideal in contrast to this king and woman who sought to deceive. The king, by hiding his skill underneath the clothing of a commoner, is tricking his opponents into losing. The woman by appearing foreign, is using her apparent exoticness to entice competitors into thinking her a rarer prize. Small wonder then that Morien catches sight of something that appears ideal (but is in his imagination), a red and yellow nothing that reminds him he is being diverted from his quest.

Continuing his exhausting journey, Morien is struggling to keep a grip on reality. In XII, catching a rare night’s sleep in a hermitage:

His lids flutter, the hatched lashes betray a milky slit. On it:

the surface of a dream in which a hermitage roof slid down

a century ago and left a jagged aperture above. Below,

Morien appears skeletal and genderqueer:

promise that you

will

sing

about me.

Occasionally a modern colloquialism slips in to draw attention to a particular point. Morien’s nightmare reminds him of his quest: to find a father who left before he was born and the unvoiced fear of rejection. Rejection would undo Morien’s identity as the son of a knight.

The Red and Yellow Nothing is an exploration of identity, primarily through race, using its medieval setting to get away from modern labelling and to encourage readers to think about their own prejudices. The poems are rich in detail but remain mindful to need to progress a plot and tell the story.

.

Emma Lee’s most recent collection is Ghosts in the Desert (Indigo Dreams, 2015). She was co-editor for Over Land Over Sea: poems for those seeking refuge (Five Leaves, 2015) and blogs at http://emmalee1.wordpress.com

Jay Bernard’s collection tells an ancient story in which Emma Lee finds some modern resonances

Winner of the sixth Cafe Writers Commission judged by Kate Birch, Chris Gribble and Helen Ivory, The Red and Yellow Nothing explores Sir Morien’s search for his father, Sir Agloval, a knight of King Arthur’s Round Table. It’s loosely a prequel to Morien: A Metrical Romance Rendered into English from the Middle Dutch, translated by Jessie Laidlay Weston (1901). Morien travels from Moorish lands to England to start his quest to find his father, in a sequence split into 13 parts, each starting with a stage direction. In II, the introduction suggests maybe we can empathise with the frustration one feels when the local people take one look at you, then hurry away from you before you’ve finished your sentence. Here, Morien asks a bard:

Naturally someone who’s trained as a knight since childhood would instinctively and as a reflex turn to his sword. The bard sings a story of a knight setting out on a quest but cannot answer Morien’s questions directly, giving rise to frustration. Readers don’t know who the everyone referred to is. Are they unarmed commoners wary of a knight’s sword? Are they being truthful about not knowing where Sir Agloval is? Do they refuse to answer because they are naturally suspicious of a stranger or because of some other prejudice? In not spelling out that Morien is black, Jay Bernard allows the readers to explore ideas around racial prejudice without directly being told this is the issue.

In III, Morien joins a competition where the prize is a kiss from a black lady; but he loses to a wild man who turns out to be a king. And as he kisses the black woman, the other men form a line, they pressed their mouths against the woman’s ass, laughing. The woman is revealed to be white.

The richness of detail, particularly of smell, is apt. By showing, the poet doesn’t need to remind readers these are historical times. Morien loses the woman wearing red and yellow in the crowd and realises she was a figment of his imagination, an ideal in contrast to this king and woman who sought to deceive. The king, by hiding his skill underneath the clothing of a commoner, is tricking his opponents into losing. The woman by appearing foreign, is using her apparent exoticness to entice competitors into thinking her a rarer prize. Small wonder then that Morien catches sight of something that appears ideal (but is in his imagination), a red and yellow nothing that reminds him he is being diverted from his quest.

Continuing his exhausting journey, Morien is struggling to keep a grip on reality. In XII, catching a rare night’s sleep in a hermitage:

His lids flutter, the hatched lashes betray a milky slit. On it: the surface of a dream in which a hermitage roof slid down a century ago and left a jagged aperture above. Below, Morien appears skeletal and genderqueer: promise that you will sing about me.Occasionally a modern colloquialism slips in to draw attention to a particular point. Morien’s nightmare reminds him of his quest: to find a father who left before he was born and the unvoiced fear of rejection. Rejection would undo Morien’s identity as the son of a knight.

The Red and Yellow Nothing is an exploration of identity, primarily through race, using its medieval setting to get away from modern labelling and to encourage readers to think about their own prejudices. The poems are rich in detail but remain mindful to need to progress a plot and tell the story.

.

Emma Lee’s most recent collection is Ghosts in the Desert (Indigo Dreams, 2015). She was co-editor for Over Land Over Sea: poems for those seeking refuge (Five Leaves, 2015) and blogs at http://emmalee1.wordpress.com

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2016 2 • Tags: books, Emma Lee, poetry