Richie McCaffery considers the life and work of G S Fraser in the context of a new selection of his poetry from Shoestring Press

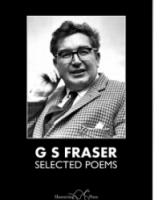

Selected Poems

G S Fraser

Shoestring Press

ISBN: 978-1-910323-36-6

80 pp £10.00

Selected Poems

G S Fraser

Shoestring Press

ISBN: 978-1-910323-36-6

80 pp £10.00

Andrew Waterman, in his introduction to this book (which adds value and biographical interest to the poems that follow) writes that George Sutherland Fraser (1915-1980) as a poet ‘was not assignable to any group of the kind commentators find convenient’. Even before I had heard this book was being published, I was reconsidering the position of G. S. Fraser, who I now consider an important diasporic Scottish poet. By this I mean he was a poet who, by volition or circumstance, ended up living at a remove from Scotland (he was born in Glasgow, and educated in St Andrews and Aberdeen before spending the rest of his life in Chelsea, Tokyo and Leicester), while still keeping a vigilant eye on Scotland’s affairs. We can see this in his first full collection Home Town Elegy (published by Tambimuttu’s Poetry London Editions while Fraser was serving in the British Army in Cairo during the war) where Fraser interrogates Scotland and its poets, using the poem ‘To Hugh MacDiarmid’ to explain the difference of his stance – that he will speak for himself and not a nation and a history, like MacDiarmid often did:

What a race has is always crude and common,

And not the human or the personal:

I would take sword up only for the human,

Not to revive the broken ghosts of Gael.

Waterman argues that for Fraser ‘narrow nationalism fettered imaginative freedom’, but I would disagree that MacDiarmid’s nationalism could ever be easily labelled as ‘narrow’. The separateness of Fraser’s position, alone and outside of Scotland, gives us some sense of his neglect as a poet. In a private letter (dated 19/12/1970) to the poet Maurice Lindsay, Fraser considered his position as a Scottish poet, after reading a piece of harsh criticism of his work by poet and academic Alexander Scott:

I am in a rather melancholy mood about my reputation as a poet (…) Alexander Scott (…) says I never

wrote a good poem after 1943 – all the rest is ‘sentimental’ or in the worst sense ‘academic’ (…)

I don’t know why Alex Scott dislikes me so much (…) I am just as typically Scottish as he is.

I recall once being asked whether I thought Fraser was too ‘Establishment’ a poet to be considered alongside Scottish poets of his era. It is certainly true that he existed, as David Robb (Alexander Scott’s biographer) claims, ‘in the centre of an established world’ and was a ‘Scottish man of letters who did not commit to Scotland’ but his poetry, since his death, has been marginalised critically. Perhaps this is partly ascribable to his rejection by certain Scottish poets who were his contemporaries, such as Alexander Scott, and his Scottish identity which might have put distance between himself and some of his more typically ‘Establishment’ contemporaries and friends in England. Some of Fraser’s journalism and recollections in his memoirs A Stranger and Afraid show that Fraser was often warmly disposed to Scottish poets such as Hamish Henderson and often enjoyed the literary pub scene in Edinburgh in the 1950s and 1960s, yet he remained the ‘stranger’. In addition, behind the scant writing that exists about Fraser the word ‘dilettante’ hovers awkwardly – was he a figure who never devoted himself fully to one particular literary endeavour? As to all of his literary, poetic, journalistic and educational work that might have got in the way of simply writing more poems, his wife Paddy (1918-2013) was to write in her memoir of life with Fraser that he was simply fascinated by poetry in all its forms and that was his life. In ‘A Letter to Anne Ridler’ the speaker declares:

I bore the seed of poetry from my birth

To flower in rocky ground, sporadically,

Until I sleep in the unlaurelled night.

This passion for the poetry of others is shown in moving poems for friends such as the tragic poet Veronica Forrest Thomson (1947-1975). In his technically nimble, but rather traditional verse he praises youth and youthful poetic innovation:

A prosy poem, this, about a new poetics:

But young poets are looking for a new poetics:

People write to me, people talk to me, insights come:

The soul’s dark cottage, battered and decay’d,

Lets in new light through chinks that Time has made.

from: ‘Two Letters from, and a Conversation with a Poet’

In the extract above, Fraser demonstrates the streak of self-deprecation that characterises much of his verse, a technique he also used in ‘To Hugh MacDiarmid’. Reading this Selected Poems in its entirety shows a curiously torn poet, one simultaneously aware of his shortcomings as well as his cultural worth, such as in the blackly, bitterly playful lines of ‘Home Thoughts on Ireland’:

I shall go to Sligo this August and lecture on

‘The Influence of Yeats’. And if they shoot me,

Or blow me up, in the Town Hall, in mid-quotation,

It will be after all a nice last touch.

For an otherwise tepid Times obituary.

I welcome this handsome, although lean, selection of some of his finer poems. It would be good to know who made the selection – was it John Lucas, the editor and publisher, or Andrew Waterman, who provided the generous preface? That aside, the selection is very good, ranging chronologically from Fraser’s most anthologised early poem ‘Lean Street’ through to the deeply poignant ‘High Dam’, an unfinished poem found on Fraser’s desk after his death:

We cannot always catch the ball

But our opponent throws it high,

High up still still, piled clouded sky.

The day comes when the leaf must fall.

There is a koan-like quality to some of Fraser’s poems, and a late attempt to find peace in family life in his later ones, perhaps derived from his time spent teaching in Japan. The selection begins with angrier, more disenchanted poetry, such as the critique of MacDiarmid, or ‘Lean Street’ where The fat sky gurgles like a swollen bladder / With the foul rain that rains on poverty or ‘Meditation of a Patriot’ which contains the revealing lines:

My heart yearns southwards as the shadows slant,

I wish I were an exile and I rave:

With Byron and with Lermontov

Romantic Scotland’s in the grave.

Again, Fraser does not seem to belong easily to any literary movement. He is too old to be an ‘Angry Young Man’, too young to be one of the ‘Pylon School’, not as coldly rational as ‘the Movement’ poets, and too rational and clear to be a ‘New Apocalyptic’. Furthermore, he stands aside from the Lallans makars and the Scottish Literary Renaissance. Indeed, in poems such as ‘Christmas Letter Home’, where the poet writes to a sister in Scotland, Fraser declares his suspicion of poster-poetry and propaganda as well as his unbridgeable distance from Scotland:

‘These years were painful, then?’ ‘I hardly know.

Something lies gently over them, like snow,

A sort of numbing white forgetfulness…’

And again, in ‘The Traveller has Regrets’ Fraser dramatizes the feeling of not fitting in, or belonging:

But the blue lights on the hill,

The white lights in the bay

Told us the meal was laid

And that the bed was made

And that we could not stay.

These poems show Fraser to be a masterly poet of occasion – not a poet who dabbles or writes occasionally, but a poet who can only be spurred into verse by momentous events or special commemorations, such as epistles to other poets, the birthdays of William Empson and his daughter Katie, the death of John F. Kennedy and so on. You cannot imagine Fraser working as easily and glibly as Norman MacCaig would have us believe about his own writing habits – sitting down in a chair without a thought in his head, smoking a cigarette and never revising the poem that comes from thin air. These poems are the poems of a punctilious craftsman, pored over and revised multiple times – they scan and read aloud powerfully and musically and the also contain extremely swaying aesthetic arguments. While Fraser is clearly a poet of praise and a celebrant, I think the strongest poems in this selection show the stress marks in otherwise polished and urbane work. Take for instance ‘Speech of a Sufferer’, written after Fraser’s mental breakdown in 1951; this shows Fraser’s frustration with the limitations of life that feed into his poetry, and is a startling treatment of the experience of mental illness:

Twice, too, I remember someone calling my attention

To a little bird, a lame one, just escaping

From a waiting cat: a sort of lingua franca

Perhaps of people who have just gone over the edge –

The cat our fleshly lusts, the bird the soul?

But I’ve always loved cats, and cats must eat.

You get insights but they don’t work out as logic.

But even more than this, ‘Lenten Mediation’ seems to me to go much further than Philip Larkin’s ‘This Be the Verse’ in showing and explaining how the mind of the poet is irrevocably made and disturbed by family and upbringing:

It is hard to forgive, ever, even the dead:

My father who put on an act which was not himself

But which he imposed on me: my mother who talked:

Whose talk gnawed into my thinking and self-being:

My sister whose strength was a reproach to my weakness (…)

(…) And one had

To produce love for all those who devoured one.

That is the point of Lent.

This is a remarkable and revealing selection of Fraser’s poetry and an excellent introduction for those who might not have encountered his work before. For the more seasoned reader of Fraser’s work, this book is valuable for the later poems and the introduction by Andrew Waterman. The ordering of the poems allows Fraser’s demons to be half addressed, and we see an older, dying Fraser try to achieve some sort of reconciliation in his art, in the poem ‘Older’:

Yes, I would linger if I could

At least to seem serene and brave,

Freshets beneath my grittiest mood

(And not be left all dry of love

Before the last late light decayed.)

.

Richie McCaffery (b.1986) recently completed a Carnegie Trust funded PhD on the Scottish poets of World War Two, at the University of Glasgow. He now lives in Ostend, Belgium. He is the author of Spinning Plates (2012), the 2014 Callum Macdonald Memorial Pamphlet Award runner-up, Ballast Flint and the book-length collection Cairn from Nine Arches Press, 2014. Another pamphlet, provisionally entitled Arris, is forthcoming in 2017. He is also the editor of Finishing the Picture: The Collected Poems of Ian Abbot (Kennedy and Boyd, 2015)

Richie McCaffery considers the life and work of G S Fraser in the context of a new selection of his poetry from Shoestring Press

Andrew Waterman, in his introduction to this book (which adds value and biographical interest to the poems that follow) writes that George Sutherland Fraser (1915-1980) as a poet ‘was not assignable to any group of the kind commentators find convenient’. Even before I had heard this book was being published, I was reconsidering the position of G. S. Fraser, who I now consider an important diasporic Scottish poet. By this I mean he was a poet who, by volition or circumstance, ended up living at a remove from Scotland (he was born in Glasgow, and educated in St Andrews and Aberdeen before spending the rest of his life in Chelsea, Tokyo and Leicester), while still keeping a vigilant eye on Scotland’s affairs. We can see this in his first full collection Home Town Elegy (published by Tambimuttu’s Poetry London Editions while Fraser was serving in the British Army in Cairo during the war) where Fraser interrogates Scotland and its poets, using the poem ‘To Hugh MacDiarmid’ to explain the difference of his stance – that he will speak for himself and not a nation and a history, like MacDiarmid often did:

Waterman argues that for Fraser ‘narrow nationalism fettered imaginative freedom’, but I would disagree that MacDiarmid’s nationalism could ever be easily labelled as ‘narrow’. The separateness of Fraser’s position, alone and outside of Scotland, gives us some sense of his neglect as a poet. In a private letter (dated 19/12/1970) to the poet Maurice Lindsay, Fraser considered his position as a Scottish poet, after reading a piece of harsh criticism of his work by poet and academic Alexander Scott:

I recall once being asked whether I thought Fraser was too ‘Establishment’ a poet to be considered alongside Scottish poets of his era. It is certainly true that he existed, as David Robb (Alexander Scott’s biographer) claims, ‘in the centre of an established world’ and was a ‘Scottish man of letters who did not commit to Scotland’ but his poetry, since his death, has been marginalised critically. Perhaps this is partly ascribable to his rejection by certain Scottish poets who were his contemporaries, such as Alexander Scott, and his Scottish identity which might have put distance between himself and some of his more typically ‘Establishment’ contemporaries and friends in England. Some of Fraser’s journalism and recollections in his memoirs A Stranger and Afraid show that Fraser was often warmly disposed to Scottish poets such as Hamish Henderson and often enjoyed the literary pub scene in Edinburgh in the 1950s and 1960s, yet he remained the ‘stranger’. In addition, behind the scant writing that exists about Fraser the word ‘dilettante’ hovers awkwardly – was he a figure who never devoted himself fully to one particular literary endeavour? As to all of his literary, poetic, journalistic and educational work that might have got in the way of simply writing more poems, his wife Paddy (1918-2013) was to write in her memoir of life with Fraser that he was simply fascinated by poetry in all its forms and that was his life. In ‘A Letter to Anne Ridler’ the speaker declares:

This passion for the poetry of others is shown in moving poems for friends such as the tragic poet Veronica Forrest Thomson (1947-1975). In his technically nimble, but rather traditional verse he praises youth and youthful poetic innovation:

A prosy poem, this, about a new poetics: But young poets are looking for a new poetics: People write to me, people talk to me, insights come: The soul’s dark cottage, battered and decay’d, Lets in new light through chinks that Time has made. from: ‘Two Letters from, and a Conversation with a Poet’In the extract above, Fraser demonstrates the streak of self-deprecation that characterises much of his verse, a technique he also used in ‘To Hugh MacDiarmid’. Reading this Selected Poems in its entirety shows a curiously torn poet, one simultaneously aware of his shortcomings as well as his cultural worth, such as in the blackly, bitterly playful lines of ‘Home Thoughts on Ireland’:

I welcome this handsome, although lean, selection of some of his finer poems. It would be good to know who made the selection – was it John Lucas, the editor and publisher, or Andrew Waterman, who provided the generous preface? That aside, the selection is very good, ranging chronologically from Fraser’s most anthologised early poem ‘Lean Street’ through to the deeply poignant ‘High Dam’, an unfinished poem found on Fraser’s desk after his death:

There is a koan-like quality to some of Fraser’s poems, and a late attempt to find peace in family life in his later ones, perhaps derived from his time spent teaching in Japan. The selection begins with angrier, more disenchanted poetry, such as the critique of MacDiarmid, or ‘Lean Street’ where The fat sky gurgles like a swollen bladder / With the foul rain that rains on poverty or ‘Meditation of a Patriot’ which contains the revealing lines:

Again, Fraser does not seem to belong easily to any literary movement. He is too old to be an ‘Angry Young Man’, too young to be one of the ‘Pylon School’, not as coldly rational as ‘the Movement’ poets, and too rational and clear to be a ‘New Apocalyptic’. Furthermore, he stands aside from the Lallans makars and the Scottish Literary Renaissance. Indeed, in poems such as ‘Christmas Letter Home’, where the poet writes to a sister in Scotland, Fraser declares his suspicion of poster-poetry and propaganda as well as his unbridgeable distance from Scotland:

And again, in ‘The Traveller has Regrets’ Fraser dramatizes the feeling of not fitting in, or belonging:

These poems show Fraser to be a masterly poet of occasion – not a poet who dabbles or writes occasionally, but a poet who can only be spurred into verse by momentous events or special commemorations, such as epistles to other poets, the birthdays of William Empson and his daughter Katie, the death of John F. Kennedy and so on. You cannot imagine Fraser working as easily and glibly as Norman MacCaig would have us believe about his own writing habits – sitting down in a chair without a thought in his head, smoking a cigarette and never revising the poem that comes from thin air. These poems are the poems of a punctilious craftsman, pored over and revised multiple times – they scan and read aloud powerfully and musically and the also contain extremely swaying aesthetic arguments. While Fraser is clearly a poet of praise and a celebrant, I think the strongest poems in this selection show the stress marks in otherwise polished and urbane work. Take for instance ‘Speech of a Sufferer’, written after Fraser’s mental breakdown in 1951; this shows Fraser’s frustration with the limitations of life that feed into his poetry, and is a startling treatment of the experience of mental illness:

But even more than this, ‘Lenten Mediation’ seems to me to go much further than Philip Larkin’s ‘This Be the Verse’ in showing and explaining how the mind of the poet is irrevocably made and disturbed by family and upbringing:

This is a remarkable and revealing selection of Fraser’s poetry and an excellent introduction for those who might not have encountered his work before. For the more seasoned reader of Fraser’s work, this book is valuable for the later poems and the introduction by Andrew Waterman. The ordering of the poems allows Fraser’s demons to be half addressed, and we see an older, dying Fraser try to achieve some sort of reconciliation in his art, in the poem ‘Older’:

.

Richie McCaffery (b.1986) recently completed a Carnegie Trust funded PhD on the Scottish poets of World War Two, at the University of Glasgow. He now lives in Ostend, Belgium. He is the author of Spinning Plates (2012), the 2014 Callum Macdonald Memorial Pamphlet Award runner-up, Ballast Flint and the book-length collection Cairn from Nine Arches Press, 2014. Another pamphlet, provisionally entitled Arris, is forthcoming in 2017. He is also the editor of Finishing the Picture: The Collected Poems of Ian Abbot (Kennedy and Boyd, 2015)

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • authors, books, poetry reviews, year 2015 0