Peter Daniels takes a close look at the techniques and themes in Andrew McMillan’s collection

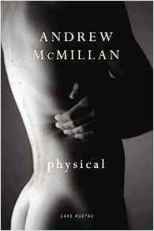

physical

Andrew McMillan

Cape,

ISBN 978-0-224-10213-1

53pp £10

physical

Andrew McMillan

Cape,

ISBN 978-0-224-10213-1

53pp £10

This is a review by a gay man more than twice McMillan’s age: in his poems a lot of youthful sex is being had, not in detail but well understood; a certain amount of breaking up with lovers, not too woundingly but leaving necessary scars; and much frequenting of clubs and gyms where gay masculinity and masculinity in general are observed, enjoyed, and gently satirised. There is explicit homage to Thom Gunn, an older poet now ten years dead, whose first book appeared the year I was born. Notably absent aspects of gay experience to a man of my generation are first-person anguishing about being gay, and anything about AIDS (rampant in 1988, McMillan’s birth year) or ongoing concerns about HIV. Lack of hangup about sexual identity is a bonus of generally better times, while he can hardly be unware of Gunn’s poems about AIDS, and the situation being different now though not over: this is not to say ‘Why are these subjects not represented to satisfy my expectations of tragedy?’, but it is worth remarking. Other things are not there because he’s a young poet and doesn’t have the view of the world from whatever happens in the next thirty years. No need for patronising remarks about any of that, and perhaps he’s anticipating it with we were young we only had our bodies (‘a gift’) – though I think he’s only looking back from now to when he was still younger.

Queer theory endlessly discusses bodies, what we do with them, who we are in them: these poems are practice, not theory, although the middle section of the three has ‘theory’ as one of its repeated motifs – theory we’re sums of our parts, theory we’re sums of our partners, theory the moon isn’t just for poets – but as a way of making sense of life, not intellectualising about it. This section, ‘protest of the physical’ is a fragmentary poem taking 14 pages but with a lot of space built in, gathering itself through repeated phrases, images, experiences, obsessions: others include a crane over a car park and other urban views; Barnsley (or Baaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaarnslie); graffiti; fire, nakedness, and the two combined; men fighting, men having sex, maybe both at once.

Thom Gunn and the poet’s hero-worship of him is at the centre of ‘protest of the physical’, with the book of Gunn’s poems representing him as sexual partner – sleep with Thom night after night / open at the spine face pushed deep. Gunn’s own recurrent theme of masculinity and heroes sends ripples through the poem and the book as a whole, though mostly less evident than McMillan’s Guardian account of the influence might suggest: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/aug/08/my-hero-thom-gunn-us-poet-andrew-mcmillan. Only one other poem directly refers to Gunn, ‘Saturday night’, called a ‘broken cento’: more a kind of glose (used by poets like Marilyn Hacker), as a cento takes lines from multiple poems while this takes parts of one Gunn poem, sandwiched with McMillan’s lines. The Gunn lines looking back to pre-AIDS San Francisco feel somewhat lost and denatured in the midst of McMillan’s recounting his own Saturday night, and this brings in questions about McMillan’s form, not much like Gunn’s: very consistent and up to a point distinctive, but maybe limiting.

All the poems are unpunctuated except for occasional question marks, though gaps and line breaks also act as punctuation; everything is lower case except proper names. The need for question marks shows up the lack of guidance for speech tone from other punctuation, so McMillan’s lines float through the book in tonal mid-air, which can begin to feel like a written equivalent of Poetry Voice. The ‘protest of the physical’ section contains more gaps, arranging groups of lines either side of the page, which feels more positive as a formal strategy; but here and elsewhere some line breaks disrupt the flow without much effect except disruption, and tricky ones try having it both ways like I knew / that you would end up loving me too / much (‘screen’) which feels like a trick played on the reader who gets the line wrong.

This lack of expressive signposts has a purpose, reflecting the masculine problem with feelings, a major subject in the collection: as in the deadpan delivery of ‘the men are weeping in the gym’ –

swearing that the wetness

on their cheeks is perspiration

that the words they mutter as they lift

are meaningless

Gym culture is a major junction for gay and straight masculinities; while exploring male attitudes in male-male sexual relationships, McMillan pays attention to maleness in general, which connects also to Northernness, the Northern man’s way with feelings. The version of Egill Skallagrímsson’s Norse suggests how far back male self-destructiveness goes:

I am deadheavydrunk

sharpen penblade moonglint

now think of Hemingway

swallowing a shotgun

There is an Alan Bennett multi-negative style of defence against positivity in just because I do this doesn’t mean / not knowing names doesn’t make it something less, and a Yorkshire domestic scene plays out in ‘how to be a man’, about the death of a grandfather. A problem here is that everyone is tactful not to mention McMillan’s well-known father, in this poem so present as himself it seems hard to judge how well the poet creates the scene, even with expressive lines like see your dad’s face like an empty box. The opening poem ‘Jacob with the angel’ uses the sexual physicality of wrestling with a stranger which just happen as an inevitable grounding myth for men finding themselves in intimacy (in ‘Leda to her daughters’, the other mythological poem, the comment on masculinity from sex with a swan is inevitably less grounded). Masculinity and Northernness bring McMillan’s work somewhere beyond ‘gay poetry’, though still in the area of ‘identity’ and the concerns of the physical explicit in the title. I’ll look forward to his next stage: the exploratory blend in ‘protest of the physical’ could be where it begins.

.

Peter Daniels has won several competitions including the Arvon, Ledbury and TLS. He has published pamphlets including the obscene historical Ballad of Captain Rigby, the full collection Counting Eggs (2012), and translations of Vladislav Khodasevich from Russian (2013).

Peter Daniels takes a close look at the techniques and themes in Andrew McMillan’s collection

This is a review by a gay man more than twice McMillan’s age: in his poems a lot of youthful sex is being had, not in detail but well understood; a certain amount of breaking up with lovers, not too woundingly but leaving necessary scars; and much frequenting of clubs and gyms where gay masculinity and masculinity in general are observed, enjoyed, and gently satirised. There is explicit homage to Thom Gunn, an older poet now ten years dead, whose first book appeared the year I was born. Notably absent aspects of gay experience to a man of my generation are first-person anguishing about being gay, and anything about AIDS (rampant in 1988, McMillan’s birth year) or ongoing concerns about HIV. Lack of hangup about sexual identity is a bonus of generally better times, while he can hardly be unware of Gunn’s poems about AIDS, and the situation being different now though not over: this is not to say ‘Why are these subjects not represented to satisfy my expectations of tragedy?’, but it is worth remarking. Other things are not there because he’s a young poet and doesn’t have the view of the world from whatever happens in the next thirty years. No need for patronising remarks about any of that, and perhaps he’s anticipating it with we were young we only had our bodies (‘a gift’) – though I think he’s only looking back from now to when he was still younger.

Queer theory endlessly discusses bodies, what we do with them, who we are in them: these poems are practice, not theory, although the middle section of the three has ‘theory’ as one of its repeated motifs – theory we’re sums of our parts, theory we’re sums of our partners, theory the moon isn’t just for poets – but as a way of making sense of life, not intellectualising about it. This section, ‘protest of the physical’ is a fragmentary poem taking 14 pages but with a lot of space built in, gathering itself through repeated phrases, images, experiences, obsessions: others include a crane over a car park and other urban views; Barnsley (or Baaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaarnslie); graffiti; fire, nakedness, and the two combined; men fighting, men having sex, maybe both at once.

Thom Gunn and the poet’s hero-worship of him is at the centre of ‘protest of the physical’, with the book of Gunn’s poems representing him as sexual partner – sleep with Thom night after night / open at the spine face pushed deep. Gunn’s own recurrent theme of masculinity and heroes sends ripples through the poem and the book as a whole, though mostly less evident than McMillan’s Guardian account of the influence might suggest: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/aug/08/my-hero-thom-gunn-us-poet-andrew-mcmillan. Only one other poem directly refers to Gunn, ‘Saturday night’, called a ‘broken cento’: more a kind of glose (used by poets like Marilyn Hacker), as a cento takes lines from multiple poems while this takes parts of one Gunn poem, sandwiched with McMillan’s lines. The Gunn lines looking back to pre-AIDS San Francisco feel somewhat lost and denatured in the midst of McMillan’s recounting his own Saturday night, and this brings in questions about McMillan’s form, not much like Gunn’s: very consistent and up to a point distinctive, but maybe limiting.

All the poems are unpunctuated except for occasional question marks, though gaps and line breaks also act as punctuation; everything is lower case except proper names. The need for question marks shows up the lack of guidance for speech tone from other punctuation, so McMillan’s lines float through the book in tonal mid-air, which can begin to feel like a written equivalent of Poetry Voice. The ‘protest of the physical’ section contains more gaps, arranging groups of lines either side of the page, which feels more positive as a formal strategy; but here and elsewhere some line breaks disrupt the flow without much effect except disruption, and tricky ones try having it both ways like I knew / that you would end up loving me too / much (‘screen’) which feels like a trick played on the reader who gets the line wrong.

This lack of expressive signposts has a purpose, reflecting the masculine problem with feelings, a major subject in the collection: as in the deadpan delivery of ‘the men are weeping in the gym’ –

Gym culture is a major junction for gay and straight masculinities; while exploring male attitudes in male-male sexual relationships, McMillan pays attention to maleness in general, which connects also to Northernness, the Northern man’s way with feelings. The version of Egill Skallagrímsson’s Norse suggests how far back male self-destructiveness goes:

There is an Alan Bennett multi-negative style of defence against positivity in just because I do this doesn’t mean / not knowing names doesn’t make it something less, and a Yorkshire domestic scene plays out in ‘how to be a man’, about the death of a grandfather. A problem here is that everyone is tactful not to mention McMillan’s well-known father, in this poem so present as himself it seems hard to judge how well the poet creates the scene, even with expressive lines like see your dad’s face like an empty box. The opening poem ‘Jacob with the angel’ uses the sexual physicality of wrestling with a stranger which just happen as an inevitable grounding myth for men finding themselves in intimacy (in ‘Leda to her daughters’, the other mythological poem, the comment on masculinity from sex with a swan is inevitably less grounded). Masculinity and Northernness bring McMillan’s work somewhere beyond ‘gay poetry’, though still in the area of ‘identity’ and the concerns of the physical explicit in the title. I’ll look forward to his next stage: the exploratory blend in ‘protest of the physical’ could be where it begins.

.

Peter Daniels has won several competitions including the Arvon, Ledbury and TLS. He has published pamphlets including the obscene historical Ballad of Captain Rigby, the full collection Counting Eggs (2012), and translations of Vladislav Khodasevich from Russian (2013).

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2015 0