Paul Henry’s latest collection shows him still to be a master of the distinctively vivid descriptive line.

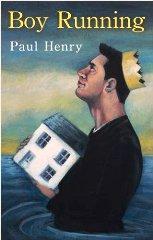

Boy Running

Paul Henry

Seren Books

ISBN 978-1-78172-226-8

72 pp £9.99

Boy Running

Paul Henry

Seren Books

ISBN 978-1-78172-226-8

72 pp £9.99

Paul Henry’s new collection Boy Running contains three sections: ‘Studio Flat’ deals with the dislocations of life after a marriage breaks up; ‘Kicking the Stone’ follows a small boy as he wanders through memories of a 1960s housing estate; and ‘Davy Blackrock’ transposes the story of an 18th century musician into the present day. Three distinct groups of poems – yet their themes and images intertwine and overlap.

The first section begins with the painful process of moving out of one life and into another. In ‘Usk’, the poet tells us Here is where my past begins // in a garret beside a bridge. In ‘Studio Flat’ he faces the aching question And where are you, my sons? – and ‘Usk’ has already provided the answer that they are present only in their holiday grins/ on every bookcase. Initially, objects, such as photographs, are what chiefly preoccupy the poet/narrator as he seeks a new context for himself. Two fine and pared-down poems ‘Ring’ and ‘Piano’ capture the large and the small of it. At one extreme I can’t get the ring out of my finger/…/ this ghost ring, twenty years deep; and at the other there is First shame, then guilt, then a piano – / you left me this piano. / It strikes me I buried you inside it.

Mentions of doors, windows and skylights suggest possibilities of escape or refreshment or illumination; but doors may prove to be closed and skylights are sometimes darkened. Many readers will have had dreams like the one in which the poet rings the bell of a house where he no longer belongs and offers the sorry excuse I’ve lost my keys. It is not only doors that have keys: a stopped clock may stand between the poet and his future:

Either I wind it now

and believe there is time

beyond seven twenty-five

...

or I post you the key

Later in the section, the poet allows his gaze to move away from domestic objects and furnishings around him and he begins to speculate about the lives of other people – like the picture framer responsible for the displayed photos of his boys on the bookcase. He writes to an absent landlord, complaining about the man in the upstairs flat (who, one suspects, is himself): He is too quiet. / His thoughts are deafening. Particularly movingly, in ‘St Julia’s Prayer’, he looks for ways in which consolation might reach him in his solitude:

I’ve closed the skylight for the night.

I hope that your prayer slipped in

in time, and was not too exhausted

...

The lamplight makes me monstrous

on the far wall. Perhaps your prayer

forgives such ugliness...

The poems in this fine opening sequence are likely to find the tender spots in the psyche of anyone who has at some time felt themselves to be bereft.

‘Kicking the Stone’ takes us on a journey through remembered suburban streets with the suggestion that former residents are all dead: In place of graves, front doors / name the neighbours. But a few lines further on he imagines a kind of resurrection as

... all of the doors

open their lids

with a deafening roar

As the boy and the stone make their erratic way up the road we meet the inhabitants – or at least we see some traces of their presence. For instance

The Bachelor’s in the boot

of his latest Anglia

testing the suspension.

He keeps on his cap and coat

I wonder if it is Henry’s intention that I should be reminded here of Lennon & McCartney’s banker with a motor car who never wears a mac in the pouring rain. ‘Penny Lane’ is certainly from the same period as the one in which the poem is set. There seem to be other playful allusions in the lines which follow. It may be stretching a point to see a hint at Heaney’s ‘A Constable Calls’ in the observation A bicycle sleeps on its side, its back wheel still spinning, … Tick,tick,tick,tick; but there can surely be little doubt about the implied reference behind the speculation Do I dare to / ring a bell?

It is also plausible to infer that the boy kicking the stone is Henry himself. The descriptions of estate life are an adult’s skilful honing of a child’s experiences. They range from imaginatively accurate observation of children priestly in duffel coats or the one white hair / in Siân’s ginger dizziness to a fantastical account of a tea-trolley whose brakes don’t work.

Its scones wear goggles,

hold the tatted doilies down.

Its casters laugh, hysterically

as they round the barking bend.

It is quite something to coin a variation on ‘barking mad’ and sound a little Dylan Thomas-ish at the same time. Such artful language captures both the precision and the craziness of memory running free.

The main character in the book’s third section is Davy Blackrock. The back cover describes him as ‘a washed-up songwriter’ and calls him an alter ego of a real 18th century harpist called David of the White Rock. But of course Davy Blackrock has much in common with Henry himself, who is also a musician, singer and composer. The poems bear some similarity to the bleak household descriptions in ‘Studio Flat’: A tap warbles all night /in Blackrock’s flat / where the mice have wings. Blackrock’s ‘bedsit years’ owned a rent book / and sometimes fell behind and they sang between cracked walls / made plans, murdered mice. But they also slipped a silver ring/ onto Blackrock’s finger. It shone / when he played to his children. And from this point on, the trajectory of Blackrock’s story – his song writing, his touring, his successes – curves back towards the possibility of loss and the memories of a boy skimming stones / with his old man and the dreams of a man who inspects his clouds through a skylight much like the one through which St Julia’s prayer might have slipped in.

This is a book whose power is extended with each re-reading. Much of its conviction comes from Henry’s often startling ability to make us look afresh at familiar things in ways which give us a glimpse into the emotions of others. Observations like Socks hang like bats from the skylight and conjectures such as What’s an attic / but a bungalow in the sky are as memorable as lines of Henry’s which still come back to me from his earlier book captive audience (1996): The Sorting-Office factory-farms the mail; and (sadly appropriate to this new book) Glazed marriages hang by a single nail. Henry’s skills have clearly not diminished in the last twenty years.

.

. Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

Paul Henry’s latest collection shows him still to be a master of the distinctively vivid descriptive line.

Paul Henry’s new collection Boy Running contains three sections: ‘Studio Flat’ deals with the dislocations of life after a marriage breaks up; ‘Kicking the Stone’ follows a small boy as he wanders through memories of a 1960s housing estate; and ‘Davy Blackrock’ transposes the story of an 18th century musician into the present day. Three distinct groups of poems – yet their themes and images intertwine and overlap.

The first section begins with the painful process of moving out of one life and into another. In ‘Usk’, the poet tells us Here is where my past begins // in a garret beside a bridge. In ‘Studio Flat’ he faces the aching question And where are you, my sons? – and ‘Usk’ has already provided the answer that they are present only in their holiday grins/ on every bookcase. Initially, objects, such as photographs, are what chiefly preoccupy the poet/narrator as he seeks a new context for himself. Two fine and pared-down poems ‘Ring’ and ‘Piano’ capture the large and the small of it. At one extreme I can’t get the ring out of my finger/…/ this ghost ring, twenty years deep; and at the other there is First shame, then guilt, then a piano – / you left me this piano. / It strikes me I buried you inside it.

Mentions of doors, windows and skylights suggest possibilities of escape or refreshment or illumination; but doors may prove to be closed and skylights are sometimes darkened. Many readers will have had dreams like the one in which the poet rings the bell of a house where he no longer belongs and offers the sorry excuse I’ve lost my keys. It is not only doors that have keys: a stopped clock may stand between the poet and his future:

Later in the section, the poet allows his gaze to move away from domestic objects and furnishings around him and he begins to speculate about the lives of other people – like the picture framer responsible for the displayed photos of his boys on the bookcase. He writes to an absent landlord, complaining about the man in the upstairs flat (who, one suspects, is himself): He is too quiet. / His thoughts are deafening. Particularly movingly, in ‘St Julia’s Prayer’, he looks for ways in which consolation might reach him in his solitude:

The poems in this fine opening sequence are likely to find the tender spots in the psyche of anyone who has at some time felt themselves to be bereft.

‘Kicking the Stone’ takes us on a journey through remembered suburban streets with the suggestion that former residents are all dead: In place of graves, front doors / name the neighbours. But a few lines further on he imagines a kind of resurrection as

As the boy and the stone make their erratic way up the road we meet the inhabitants – or at least we see some traces of their presence. For instance

I wonder if it is Henry’s intention that I should be reminded here of Lennon & McCartney’s banker with a motor car who never wears a mac in the pouring rain. ‘Penny Lane’ is certainly from the same period as the one in which the poem is set. There seem to be other playful allusions in the lines which follow. It may be stretching a point to see a hint at Heaney’s ‘A Constable Calls’ in the observation A bicycle sleeps on its side, its back wheel still spinning, … Tick,tick,tick,tick; but there can surely be little doubt about the implied reference behind the speculation Do I dare to / ring a bell?

It is also plausible to infer that the boy kicking the stone is Henry himself. The descriptions of estate life are an adult’s skilful honing of a child’s experiences. They range from imaginatively accurate observation of children priestly in duffel coats or the one white hair / in Siân’s ginger dizziness to a fantastical account of a tea-trolley whose brakes don’t work.

It is quite something to coin a variation on ‘barking mad’ and sound a little Dylan Thomas-ish at the same time. Such artful language captures both the precision and the craziness of memory running free.

The main character in the book’s third section is Davy Blackrock. The back cover describes him as ‘a washed-up songwriter’ and calls him an alter ego of a real 18th century harpist called David of the White Rock. But of course Davy Blackrock has much in common with Henry himself, who is also a musician, singer and composer. The poems bear some similarity to the bleak household descriptions in ‘Studio Flat’: A tap warbles all night /in Blackrock’s flat / where the mice have wings. Blackrock’s ‘bedsit years’ owned a rent book / and sometimes fell behind and they sang between cracked walls / made plans, murdered mice. But they also slipped a silver ring/ onto Blackrock’s finger. It shone / when he played to his children. And from this point on, the trajectory of Blackrock’s story – his song writing, his touring, his successes – curves back towards the possibility of loss and the memories of a boy skimming stones / with his old man and the dreams of a man who inspects his clouds through a skylight much like the one through which St Julia’s prayer might have slipped in.

This is a book whose power is extended with each re-reading. Much of its conviction comes from Henry’s often startling ability to make us look afresh at familiar things in ways which give us a glimpse into the emotions of others. Observations like Socks hang like bats from the skylight and conjectures such as What’s an attic / but a bungalow in the sky are as memorable as lines of Henry’s which still come back to me from his earlier book captive audience (1996): The Sorting-Office factory-farms the mail; and (sadly appropriate to this new book) Glazed marriages hang by a single nail. Henry’s skills have clearly not diminished in the last twenty years.

.

. Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2015 0