Josh Ekroy observes that Owen Gallagher has attempted a monumental task in his latest collection

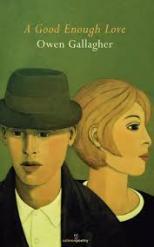

A Good Enough Love

Owen Gallagher

Salmon Poetry

ISBN 978-1-910669-19-8

55pages 12 euros

.

.

.

A Good Enough Love

Owen Gallagher

Salmon Poetry

ISBN 978-1-910669-19-8

55pages 12 euros

.

.

.

Owen Gallagher’s collection Tea With The Taliban (Smokestack, 2012) was more subversive than this. It addressed more public issues and his poems have appeared in The Morning Star (now, surely, more than ever a badge of honour) as well as the leftist website, Militant Thistles.

A Good Enough Love, through carefully crafted statements, is more interested in the personal interchanges involved in love and sex . It’s salted with wit and astute insight. The first section, which is often rueful, is called ‘Recycling Love’:

Unable to make her come

once again, I lie back whilst she gropes

for the vibrator,

and listen to its hum.

(‘Complicity’)

I like the placing of that once again, don’t you? The woman is having an affair, and the speaker is acquiescent, surprised by his own lack of jealousy. The overt rhyme is fairly typical of many of these sideways sallies into the bedroom.

But the most commonly used word, apart from the eponymous love, is day/s. The temporary nature of feeling is constantly explored, as here, where the first three words form a refrain:

On a day when love is not available

we long for sunset,

for arms to part the dark.

(‘Not All Days’)

Available is a troubling choice of adjective: love as commodity is never far away. The clipped assonance of the third line feels consigned to emptiness. There is, of course, an art to the short poem, and Gallagher has been described as having a “genius” for it. I’m not sure that the resonances in the poems in this section (the first fifteen pages) demonstrate that, but they do provoke a satisfyingly wry smile, a sad nod of recognition.

The second section – ‘Testes’ – makes for more uncomfortable reading, at least for any male reader. I assume that the reason for tackling this topic must be autobiographical. It’s hard to see why else it would be brought into play. The poems take longer to make their effect, are less insouciant, as one might expect:

Posters advertise how to feel lumps men disown,

warn of mobiles irradiating bones,

erectile difficulties, prostate cancer.

I sit in a sweat...

(‘The Men’s Clinic’)

This directness serves, by the end of the poem, to introduce an element of entrapment from which, however much the speaker would like there to be, there is no escape. Unlike ‘Reprieve’ which describes a potential suicide changing his mind when he is pissed on from a great height; the final line reads:

I took the stairs two at a time.

The third section ‘Happiness has no Forwarding Address’ also allows poetic experience go the distance. This shows to advantage in a poem such as ‘The Cure for Homosexuality’ which does not rely on oblique wit, but remains explicit until the final stanza, whose ellipsis is moving. ‘Dusty’ inhabits the feelings of a Dusty Springfield impersonator with aplomb and feeling, but ‘Burns Night’, weighted with nostalgia, delivers fewer surprises.

There is a tender imagination at work here, which, at its best, allows the sardonic to underscore the feeling and enhance it. At its more forced, it still left me interested, as in the third section’s ‘Miss Jennings’ Departure’ an extended metaphor imaging the woman composer as lover:

the skin a blank stave for her to play,

all minims, semi-breves, quavers...

You get the idea quickly enough, but there’s a pleasure in seeing it demonstrated. Something similar happens with the suitably spare ‘Bones’ which revisits the site of a demolished street the speaker once inhabited.

These are accessible, enjoyable poems which touch and amuse. There is, however, a danger of imbalance as the exploration of this monumental subject in the first section is often curtailed. Experiences could have been developed more interestingly, as they mostly are in the second two sections. A poem such as ‘Stag’ in the first section (describing the arrival of a disturbingly sexy woman at the night-before party) has trenchant detail and a provocative ending and demonstrates a willingness to do so.

.

Josh Ekroy’s first collection Ways To Build A Roadblock was published by Nine Arches Press in May, 2014. He lives in London.

Josh Ekroy observes that Owen Gallagher has attempted a monumental task in his latest collection

Owen Gallagher’s collection Tea With The Taliban (Smokestack, 2012) was more subversive than this. It addressed more public issues and his poems have appeared in The Morning Star (now, surely, more than ever a badge of honour) as well as the leftist website, Militant Thistles.

A Good Enough Love, through carefully crafted statements, is more interested in the personal interchanges involved in love and sex . It’s salted with wit and astute insight. The first section, which is often rueful, is called ‘Recycling Love’:

Unable to make her come once again, I lie back whilst she gropes for the vibrator, and listen to its hum. (‘Complicity’)I like the placing of that once again, don’t you? The woman is having an affair, and the speaker is acquiescent, surprised by his own lack of jealousy. The overt rhyme is fairly typical of many of these sideways sallies into the bedroom.

But the most commonly used word, apart from the eponymous love, is day/s. The temporary nature of feeling is constantly explored, as here, where the first three words form a refrain:

On a day when love is not available we long for sunset, for arms to part the dark. (‘Not All Days’)Available is a troubling choice of adjective: love as commodity is never far away. The clipped assonance of the third line feels consigned to emptiness. There is, of course, an art to the short poem, and Gallagher has been described as having a “genius” for it. I’m not sure that the resonances in the poems in this section (the first fifteen pages) demonstrate that, but they do provoke a satisfyingly wry smile, a sad nod of recognition.

The second section – ‘Testes’ – makes for more uncomfortable reading, at least for any male reader. I assume that the reason for tackling this topic must be autobiographical. It’s hard to see why else it would be brought into play. The poems take longer to make their effect, are less insouciant, as one might expect:

Posters advertise how to feel lumps men disown, warn of mobiles irradiating bones, erectile difficulties, prostate cancer. I sit in a sweat... (‘The Men’s Clinic’)This directness serves, by the end of the poem, to introduce an element of entrapment from which, however much the speaker would like there to be, there is no escape. Unlike ‘Reprieve’ which describes a potential suicide changing his mind when he is pissed on from a great height; the final line reads:

The third section ‘Happiness has no Forwarding Address’ also allows poetic experience go the distance. This shows to advantage in a poem such as ‘The Cure for Homosexuality’ which does not rely on oblique wit, but remains explicit until the final stanza, whose ellipsis is moving. ‘Dusty’ inhabits the feelings of a Dusty Springfield impersonator with aplomb and feeling, but ‘Burns Night’, weighted with nostalgia, delivers fewer surprises.

There is a tender imagination at work here, which, at its best, allows the sardonic to underscore the feeling and enhance it. At its more forced, it still left me interested, as in the third section’s ‘Miss Jennings’ Departure’ an extended metaphor imaging the woman composer as lover:

You get the idea quickly enough, but there’s a pleasure in seeing it demonstrated. Something similar happens with the suitably spare ‘Bones’ which revisits the site of a demolished street the speaker once inhabited.

These are accessible, enjoyable poems which touch and amuse. There is, however, a danger of imbalance as the exploration of this monumental subject in the first section is often curtailed. Experiences could have been developed more interestingly, as they mostly are in the second two sections. A poem such as ‘Stag’ in the first section (describing the arrival of a disturbingly sexy woman at the night-before party) has trenchant detail and a provocative ending and demonstrates a willingness to do so.

.

Josh Ekroy’s first collection Ways To Build A Roadblock was published by Nine Arches Press in May, 2014. He lives in London.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2015 0