Norbert Hirschhorn admires the new collection from Anne-Marie Fyfe for its carefully shaped trajectory of echoing but elusive images.

House of Small Absences

Anne-Marie Fyfe

Seren

ISBN 978-1-78172-240-4

pp 64 £9.99

.

House of Small Absences

Anne-Marie Fyfe

Seren

ISBN 978-1-78172-240-4

pp 64 £9.99

.

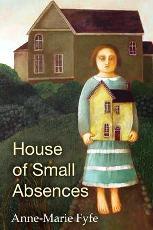

The cover illustration of this collection is a prelude to the poetry. We see a starkly simple frame house surrounded by low, dark foliage. In front stands a girl holding a flattened doll’s house that looks like, but isn’t quite, a miniature of the main house. There’s a spooky quality to this girl. She reminds me of the Victorian photographs that served as memento mori. http://www.viralnova.com/post-mortem-victorian-photographs/. She could be dead.

Anne-Marie Fyfe’s poems have that same elusive quality, on the border between what seems to be real and what is dream or hallucination, doubting their own narrative with preternatural calm. The opening poem to the sequence, ‘The Red Airplane’ illustrates the style maintained throughout. It begins with a matter-of-fact report of a small plane going down:

From the oratory window I witness

mid-air doom, a slew of concentric

swirls, a trail of forge-sparks,

and that’s it. A vermillion two-seater

stagger-wings loops earthbound,

so much depending upon centrifugal

drive….

But then, was that mere illusion, a vision?

I question now if the red bi-plane

ever was, the way sureties tilt

and untangle from any one freezeframe

to its sequel.

Perhaps the event was some distortion of reality but, in reality, the wreckage of one’s life still exists:

. What can’t be

cast in any doubt is the wreckage…

With so much depending the poem subverts William Carlos Williams’s ‘Red Wheelbarrow’: In place of his ‘no ideas but in things’, we find, rather, ‘no things but in the surreal.’

Note that the vision was from an oratory window. In old Irish churches (Fyfe hails from the Glens of Antrim) these were small, providing narrowed vision – the theme of narrow windows runs throughout the book.

What was once ‘real’ is now the stuff of artifact, like Joseph Cornell’s box- assemblages. In ‘Neuchatêl’, Fyfe presents artifacts with words: for instance, in wonderfully detailed description of long-gone aunts: Wealthy, aristocratic, full of adventure and daring (they drove self-starting cars), mouthing Stuyvesant cigarette smoke rings, holding lapdogs, sitting at triple-mirrored dressing tables, sending over-sized birthday cards with signatures in emerald green ink/and crisply folded bank-notes inside. Did they really exist, or are they the stuff of fairy tales recollected in tranquility? Their ghosts, however, are with us still:

. And if you pause a shade before

lighting-up time on a long terraced evening

you might just hear an unscheduled express hurtle

past the town’s outer avenues, packed to the luggage-racks

with those same spirited aunts, dashing all the way

down some unmarked siding to god-knows-where,

raising a dry vermouth to their vivid, elegant lives.

Cornell’s boxes are alluded to in a madhouse where shuffling delusional patients are dressed in Florentine masks,/ eye-patches, bee-keeper veils, in ‘Honey and Wild Locusts’ (inverting Matthew 3:4: John the Baptist’s food was locusts and wild honey):

It’s a cabinet of overwritten case histories,

lost infancies under key and hasp,

a nether land of biscuit-toned dolls

with identical china-blue eyes….

Entrée will be stuffed hummingbird

and nasturtiums again.

The title poem, ‘House of Small Absences’ is also set in an abandoned madhouse (barred windows), whose last inmate haunts the ruin:

. The hospital grounds’

rusting goalposts haven’t witnessed

a single full-time score this past

half-century.

The patient – another ghost – comes, like the aunts, from a far-gone era: she packs her bag nightly with an old brand of cigarettes, Kensitas; she sings Night and Day (Cole Porter, 1932). Death and disfiguration stalk the grounds: a crow, a last empty cab passing, Every watch/in Sadler’s store window-display’s gone awry.

Though Fyfe relies too heavily on epigraphs (appearing in fifteen out of forty-nine poems) that add little but visual clutter, she can use the sparest of imagery to evoke a troubling world. And example, an old-age home in Germany, in or near the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp:

Vergissmeinnicht (forget-me-not)

Unit B’s interior has reclaimed

mahogany stair-rails, tentative banisters

against her confusion.

Death is in the air, mixed together in real time and in memories (‘The past is a foreign country’ – L.P. Hartley):

. The facility’s gardener

who stamped Ravensbrück permits

on last year’s semester break spends

a day retrieving the year’s dead

foliage from ornamental fountains….

Behind the sanitizing poplars, beyond

virtuous edifices, past the barbed fence,

lie the incinerators, their peaceable roars

consuming another day’s forgetting.

We think we hold commerce with the dead through artifacts and commemoration, but in fact, it is we who have abandoned them, their loss more than ours. They are old news [‘What the Dead Don’t Know’]:

What the deceased can’t understand

is why they don’t hear from us

day-by-day, hour -by-hour.

What the departed don’t see

is how the lead story has moved on.

What the dead won’t say

is more or less what they didn’t say

when they had the chance. Diplomacy,

tact, reserve: these things endure.

The dead reside in their own nether world a thousand storeys deep, in a subterranean shadow land, a simulacrum of the world above but in strange muted light – a lifeless arctic midnight sun. [‘Lower Manhattan’, a fine pun].

Yet even the streets of the living are no more real [‘Street Scene’], like Hollywood false fronts even as you walk past. Don’t ask questions, keep moving:

Each new city block takes you further

from the grip of reality that’s already

packing-up shop behind you, shipping

for storage of the next production.

You’d do best to maintain a brisk walking pace.

We will join these dead someday, mute and forgotten. It can come suddenly, a terrible accident [‘From the Cockpit Window’], a plane crash; perhaps in the same two-seater that appeared in the first poem. And then where are we?

There’s a low-altitude nosedive, a rattle

of applause on the wing. Our world

is hurtling to sudden resolution….

Who’ll answer my entry phone? How long

before the empty the closet of shirts

and jackets, their sleeves hanging aimless.

Life is ever so contingent. In ‘The Window Washers’ twenty-four lines are given over to loving detail of the expert job performed high up a NYC skyscraper. Then the last stanza:

They’ll be through this shift by midday,

too deep into the rhythm to register

the blip of the first plane against the blue.

For me ‘The Window Washers’ is one of the best of the raft of 9/11 poems.

What I like most about this collection is its trajectory, the movement along the pages from one poem to the next; the way poems and lines echo one another. To appreciate this requires great attention from the reader and multiple readings, which ‘House of Small Absences’ both deserves and rewards.

. . Norbert Hirschhorn is a physician specializing in international public health, commended in 1993 by President Bill Clinton as an “American Health Hero.” He now lives in London and Beirut. His poems have been published in over three dozen journals, and four full collections: A Cracked River, Slow Dancer Press, London (1999); Mourning in the Presence of a Corpse (2008), and Monastery of the Moon, Dar al-Jadeed, Beirut (2012); To Sing Away the Darkest Days, Holland Park Press, London (2013). His work has won a number of prizes in the US and UK. See his website,www.bertzpoet.com

Norbert Hirschhorn admires the new collection from Anne-Marie Fyfe for its carefully shaped trajectory of echoing but elusive images.

The cover illustration of this collection is a prelude to the poetry. We see a starkly simple frame house surrounded by low, dark foliage. In front stands a girl holding a flattened doll’s house that looks like, but isn’t quite, a miniature of the main house. There’s a spooky quality to this girl. She reminds me of the Victorian photographs that served as memento mori. http://www.viralnova.com/post-mortem-victorian-photographs/. She could be dead.

Anne-Marie Fyfe’s poems have that same elusive quality, on the border between what seems to be real and what is dream or hallucination, doubting their own narrative with preternatural calm. The opening poem to the sequence, ‘The Red Airplane’ illustrates the style maintained throughout. It begins with a matter-of-fact report of a small plane going down:

But then, was that mere illusion, a vision?

Perhaps the event was some distortion of reality but, in reality, the wreckage of one’s life still exists:

. What can’t be cast in any doubt is the wreckage…With so much depending the poem subverts William Carlos Williams’s ‘Red Wheelbarrow’: In place of his ‘no ideas but in things’, we find, rather, ‘no things but in the surreal.’

Note that the vision was from an oratory window. In old Irish churches (Fyfe hails from the Glens of Antrim) these were small, providing narrowed vision – the theme of narrow windows runs throughout the book.

What was once ‘real’ is now the stuff of artifact, like Joseph Cornell’s box- assemblages. In ‘Neuchatêl’, Fyfe presents artifacts with words: for instance, in wonderfully detailed description of long-gone aunts: Wealthy, aristocratic, full of adventure and daring (they drove self-starting cars), mouthing Stuyvesant cigarette smoke rings, holding lapdogs, sitting at triple-mirrored dressing tables, sending over-sized birthday cards with signatures in emerald green ink/and crisply folded bank-notes inside. Did they really exist, or are they the stuff of fairy tales recollected in tranquility? Their ghosts, however, are with us still:

. And if you pause a shade before lighting-up time on a long terraced evening you might just hear an unscheduled express hurtle past the town’s outer avenues, packed to the luggage-racks with those same spirited aunts, dashing all the way down some unmarked siding to god-knows-where, raising a dry vermouth to their vivid, elegant lives.Cornell’s boxes are alluded to in a madhouse where shuffling delusional patients are dressed in Florentine masks,/ eye-patches, bee-keeper veils, in ‘Honey and Wild Locusts’ (inverting Matthew 3:4: John the Baptist’s food was locusts and wild honey):

The title poem, ‘House of Small Absences’ is also set in an abandoned madhouse (barred windows), whose last inmate haunts the ruin:

. The hospital grounds’ rusting goalposts haven’t witnessed a single full-time score this past half-century.The patient – another ghost – comes, like the aunts, from a far-gone era: she packs her bag nightly with an old brand of cigarettes, Kensitas; she sings Night and Day (Cole Porter, 1932). Death and disfiguration stalk the grounds: a crow, a last empty cab passing, Every watch/in Sadler’s store window-display’s gone awry.

Though Fyfe relies too heavily on epigraphs (appearing in fifteen out of forty-nine poems) that add little but visual clutter, she can use the sparest of imagery to evoke a troubling world. And example, an old-age home in Germany, in or near the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp:

Death is in the air, mixed together in real time and in memories (‘The past is a foreign country’ – L.P. Hartley):

. The facility’s gardener who stamped Ravensbrück permits on last year’s semester break spends a day retrieving the year’s dead foliage from ornamental fountains…. Behind the sanitizing poplars, beyond virtuous edifices, past the barbed fence, lie the incinerators, their peaceable roars consuming another day’s forgetting.We think we hold commerce with the dead through artifacts and commemoration, but in fact, it is we who have abandoned them, their loss more than ours. They are old news [‘What the Dead Don’t Know’]:

The dead reside in their own nether world a thousand storeys deep, in a subterranean shadow land, a simulacrum of the world above but in strange muted light – a lifeless arctic midnight sun. [‘Lower Manhattan’, a fine pun].

Yet even the streets of the living are no more real [‘Street Scene’], like Hollywood false fronts even as you walk past. Don’t ask questions, keep moving:

We will join these dead someday, mute and forgotten. It can come suddenly, a terrible accident [‘From the Cockpit Window’], a plane crash; perhaps in the same two-seater that appeared in the first poem. And then where are we?

Life is ever so contingent. In ‘The Window Washers’ twenty-four lines are given over to loving detail of the expert job performed high up a NYC skyscraper. Then the last stanza:

For me ‘The Window Washers’ is one of the best of the raft of 9/11 poems.

What I like most about this collection is its trajectory, the movement along the pages from one poem to the next; the way poems and lines echo one another. To appreciate this requires great attention from the reader and multiple readings, which ‘House of Small Absences’ both deserves and rewards.

. . Norbert Hirschhorn is a physician specializing in international public health, commended in 1993 by President Bill Clinton as an “American Health Hero.” He now lives in London and Beirut. His poems have been published in over three dozen journals, and four full collections: A Cracked River, Slow Dancer Press, London (1999); Mourning in the Presence of a Corpse (2008), and Monastery of the Moon, Dar al-Jadeed, Beirut (2012); To Sing Away the Darkest Days, Holland Park Press, London (2013). His work has won a number of prizes in the US and UK. See his website,www.bertzpoet.com

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2015 0