Wendy Klein finds that Rosie Jackson’s first full collection fulfils all the promise of her first chapbook

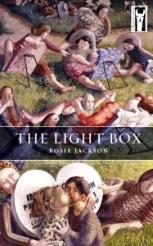

The Light Box

Rosie Jackson

Cultured Llama Publishing

ISBN 9 780993 211973

108 pp £10

The Light Box

Rosie Jackson

Cultured Llama Publishing

ISBN 9 780993 211973

108 pp £10

In January 2015, I wrote an enthusiastic review of Rosie Jackson’s first pamphlet What the Ground Holds for London Grip (the article can be found at https://londongrip.co.uk/2015/01/london-grip-poetry-review-jackson/), finishing with my anticipation of a full collection. My anticipation has been well-rewarded with this new collection from Cultured Llama Press. Jackson’s work has the ring of a confident poet writing at the height of her powers; brilliant poems from her earlier pamphlet nestling alongside new companions as brilliant.

This collection is largely inspired by visual arts; ekphrastic poems, which for me have to work hard to succeed. I find too often they tend to fall into description and interpretation that is becoming stale before it hits the page. Jackson’s are of a different order. She does not ‘describe’, but rather ‘expands’ the possibilities of paintings, in particular, Stanley Spencer’s. The book is divided into six sections, each headed by a poem based on a key Spencer painting. The poem and painting together allow for fresh ekphrastic expression as individual poems that follow are less about the subject(s) portrayed, but flow from what the painting suggests and then take off in their own magical directions. The first section, titled ‘Love’s Exuberance’ begins with a poem based on Spencer’s Love Letters (1950) An outsize armchair holds two child-like figures: a boy clasping letters to his face and chest, a girl slipping one into his pocket. In the poem, the letters Spencer actually wrote to his ex-wife Hilda, following her death, become the relationship between the couple: …he ‘cannot live, cannot breathe’ unless she writes to him again, that ‘there is no future / without this writing in it’. (‘Touch Paper’).

Each subsequent poem touches on some aspect of love recorded, particularly in its beginnings: a carnation pressed between the pages of Gibbons Decline and Fall (‘What Their Books Yield’) to the title poem, ‘The Light Box’, which addresses cross-cultural issues. Using moths to record commonalities between cultures, Jackson links

…men in Kandahar

who hand their children magnifying glasses

to marvel at exotic marks on Sphingoid moths

with

…my neighbour who shows me

his old-fashioned biscuit tin

transformed into a light box,

where moths squat like refugees

on egg boxes.

This poem heralds the impressive arc of the collection where light is shone on matters of importance, introduced via the painting, decoded by the poet.

This poet’s wide knowledge, is evident, but what of her craft? Jackson’s use of language is vivid, rich and fresh. From the section title ‘So Many Spoons’, a burst of anaphora explodes into two of my favourite lines: So many hearts swinging on thin kisses (thin kisses!), and the penultimate line: So many spoons stirring cut glasses. – glasses not glass! (‘Spoons’). She seems to write free verse as naturally as breathing, but when she drops into form, it is of equal perfection. In ‘The First Men of Light’, she takes Daguerre’s first photograph into a compressed history where the volte comes between the length of the exposure required, so long, it can only define motionless things / on the silver-/ plated copper, to the image preserved of

a proud Parisian …

a bootblack, head bowed, kneeling at his feet:

the first ghost to be caught on camera

condemned to be in service forever.

That long! She wrings emotion from a perfect sonnet, metred and rhymed, a couple break-up set in a lunar eclipse:

Then came the eclipse; that red moon rolling

fire over the ocean, and here you are,

earth’s shadow, walking to me from your car

on autumn leaves, your face implacable.

(‘Blood Moon’)

Rosie Jackson sees into the hearts and minds of her subjects, alive, dead or imagined, in a way that is not unflinching, but beyond flinching. Sensuous and heart-wrenching she portrays Mary Shelley in Hyde Park:

Always fighting to keep the membrane intact

to stop the dead pushing through,

not to see her baby in these carriages in the park,

not remember the feel of her husband’s collarbone

inside his open-necked shirt,

the drum of his heart under naked ribs.

(‘Mary Shelley, Hyde Park 1850’)

This extraordinary collection filled me with envy and joy in equal quantities. Read it and see.

Wendy Klein finds that Rosie Jackson’s first full collection fulfils all the promise of her first chapbook

In January 2015, I wrote an enthusiastic review of Rosie Jackson’s first pamphlet What the Ground Holds for London Grip (the article can be found at https://londongrip.co.uk/2015/01/london-grip-poetry-review-jackson/), finishing with my anticipation of a full collection. My anticipation has been well-rewarded with this new collection from Cultured Llama Press. Jackson’s work has the ring of a confident poet writing at the height of her powers; brilliant poems from her earlier pamphlet nestling alongside new companions as brilliant.

This collection is largely inspired by visual arts; ekphrastic poems, which for me have to work hard to succeed. I find too often they tend to fall into description and interpretation that is becoming stale before it hits the page. Jackson’s are of a different order. She does not ‘describe’, but rather ‘expands’ the possibilities of paintings, in particular, Stanley Spencer’s. The book is divided into six sections, each headed by a poem based on a key Spencer painting. The poem and painting together allow for fresh ekphrastic expression as individual poems that follow are less about the subject(s) portrayed, but flow from what the painting suggests and then take off in their own magical directions. The first section, titled ‘Love’s Exuberance’ begins with a poem based on Spencer’s Love Letters (1950) An outsize armchair holds two child-like figures: a boy clasping letters to his face and chest, a girl slipping one into his pocket. In the poem, the letters Spencer actually wrote to his ex-wife Hilda, following her death, become the relationship between the couple: …he ‘cannot live, cannot breathe’ unless she writes to him again, that ‘there is no future / without this writing in it’. (‘Touch Paper’).

Each subsequent poem touches on some aspect of love recorded, particularly in its beginnings: a carnation pressed between the pages of Gibbons Decline and Fall (‘What Their Books Yield’) to the title poem, ‘The Light Box’, which addresses cross-cultural issues. Using moths to record commonalities between cultures, Jackson links

with

This poem heralds the impressive arc of the collection where light is shone on matters of importance, introduced via the painting, decoded by the poet.

This poet’s wide knowledge, is evident, but what of her craft? Jackson’s use of language is vivid, rich and fresh. From the section title ‘So Many Spoons’, a burst of anaphora explodes into two of my favourite lines: So many hearts swinging on thin kisses (thin kisses!), and the penultimate line: So many spoons stirring cut glasses. – glasses not glass! (‘Spoons’). She seems to write free verse as naturally as breathing, but when she drops into form, it is of equal perfection. In ‘The First Men of Light’, she takes Daguerre’s first photograph into a compressed history where the volte comes between the length of the exposure required, so long, it can only define motionless things / on the silver-/ plated copper, to the image preserved of

That long! She wrings emotion from a perfect sonnet, metred and rhymed, a couple break-up set in a lunar eclipse:

Then came the eclipse; that red moon rolling fire over the ocean, and here you are, earth’s shadow, walking to me from your car on autumn leaves, your face implacable. (‘Blood Moon’)Rosie Jackson sees into the hearts and minds of her subjects, alive, dead or imagined, in a way that is not unflinching, but beyond flinching. Sensuous and heart-wrenching she portrays Mary Shelley in Hyde Park:

Always fighting to keep the membrane intact to stop the dead pushing through, not to see her baby in these carriages in the park, not remember the feel of her husband’s collarbone inside his open-necked shirt, the drum of his heart under naked ribs. (‘Mary Shelley, Hyde Park 1850’)This extraordinary collection filled me with envy and joy in equal quantities. Read it and see.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2016 0 • Tags: books, poetry, Wendy Klein