Nick Cooke is impressed by the authenticity of Stuart Laycock’s collection of poetry from the Bosnian War

Zone

Stuart Laycock

Mica Press

ISBN 978-1-869848-04-0

61 pp £7

Zone

Stuart Laycock

Mica Press

ISBN 978-1-869848-04-0

61 pp £7

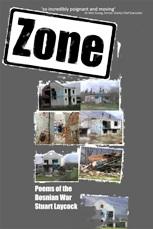

I singled out Stuart Laycock’s book for review because of an interest in its subject, the Bosnian War of the 1990s, around which I had written a poem and a stage-play. Though I did plenty of research, much of it stomach-heavingly painful even in the comfort of my armchair, Laycock’s collection puts me to shame in that I cannot say I was there, or indeed have been remotely close to any war zone, whereas, as proved by the stark and graphic photos he has included as a kind of extended centrefold to the book, he was right in the thick of the conflict, mourning the death of colleagues as he took part in seven aid missions to the country during the conflict. This biographical detail is not just a point of interest for the book’s blurb: it informs every line of every poem in this searing, deliberately underwritten collection.

Key to the overriding sense of dignified restraint is Laycock’s diction, as plain as everyday speech, often even less ornate than that, due to the way it reproduces the deadening effect of shock on the vocabulary of the war’s witnesses. A rare rhyming poem, ‘Sarajevo Cat’, is typical in another sense, that of the wry and invariably deadpan humour that runs through the collection:

The cat abandoned its doze

and went and looked through the shellhole.

It gingerly wrinkled its nose

and wondered who’d made such a hellhole.

The preceding poem is rather more characteristic of Laycock’s style, as it points out how though a lot of war reflects what happens in films in terms of fighting, explosions and death, there is also a good deal of humdrum routine and normality, or at least the illusion of it. ‘Split’ begins in apparent parody of Tennyson:

War to the south of us

war to the north of us

war, a lot of war, to the east of us

but in Split it’s Spring.

The town is desperately trying to hang on to its tourist status to the last, with people striding around in their sunshine clothes, while flowers grin from red baskets / and the only history is / Rome’s emperor Diocletian / who first built the place… Having achieved this form of ‘style indirect libre’ in conveying the locals’ efforts to focus attention on its points of historical interest, Laycock skilfully uses the simple word ‘but’ in order to catch their increasingly forced denials, as they try to suppress the realities:

Amidst the fruit and the flowers

a little stall does sell tacky,

metal war badges,

but you don’t have to stop,

. and the hotels on the outskirts

are full of refugees

but not here.

Eventually though, the truth peeps through: And the war seems / a million miles distant, / until a UN helicopter / grey white against the / cyan sky briefly disturbs / the Spring chatter. Laycock’s ending is characteristically double-edged: But soon the interruption is gone. / God, I love this place. Sardonic as his tone appears to be, this place could of course also be the country itself, genuinely loved in the way anyone would come to love somewhere being ripped apart and violated before their very eyes.

Laycock often subtly emphasises the human and societal destruction behind the physical and architectural annihilation. In ‘Gone’, he surveys a lansdscape in which Each and every house / is burnt, destroyed, / gone, kicked over / by the war boots / of the last three years. There follows an instance of rare but potent metaphor:

But the corpse of every

house lies slightly differently….

The concept of a home – as in the song, so much more than just a house – being a living and therefore potentially a dead thing, is developed through the details within the building:

…a dirty green carpet

hanging suicidally

from a now gaping bedroom,

wardrobe doors swinging open

to show abandoned clothes.

And the idea culminates in an ending which reminded me of Beckett’s Rockaby encapsulating the speaker’s utter loneliness by insisting on the lack of one other living soul:

If one single house,

just one, still lived,

big or small

(it wouldn’t matter which)

then death would

not be absolute,

the pain not half so dark.

Elsewhere, Laycock’s keenness of observation goes hand in hand with that same grim, unsentimental compassion and grief. An unforgettably downbeat elegy to his colleague Tony, one of two killed in the conflict, describes a funeral held on a spur / behind the hospital, punctuated by booms / in the background, which features Prayers in the air / and Last Post on a harmonica. Laycock’s final lines define the tone and style of his collection:

. Yep, not quite what

. a hero deserves,

. but we meant it.

Rest in peace, Tony.

There is something marvellously human, and profoundly poet-like, if not ‘poetic’, about that Yep.

Other standout pieces include ‘”Tata!”, where a blinded boy with a shadow future repeatedly and heart-breakingly calls out for his father. The poem is brought to a shattering end by another of Laycock’s occasional but memorable metaphors, as we discover that sightlessness is not the boy’s only newly-inflicted blight:

He reached with his voice.

He could no longer

reach with his right hand,

taken by the explosion

that amputated his dreams.

But it’s not all dour and grey as a UN ‘copter. Several peoms are are not so much anthems for doomed youth as quiet celebrations of its resilience. ‘Kids’ in particular plays touchingly on the theme of reality versus illusion, with a portrayal of two boys engaged in war games in the midst of a very real war. One is toting a wooden toy Kalashnikov, but the other has a real olive-green, / scratched metal, cold steel / (unloaded I hope) / grenade launcher. That parenthetical crossing of fingers is amusingly repeated in the final stanza, which sums up so much of what Laycock has achieved in this uniquely authentic and heartfelt collection:

The kid smiles and

raises the sights

raises the (empty I think)

tube on this shoulder

and still smiling shyly

aims the launcher at us,

as if at a friend.

Nick Cooke is impressed by the authenticity of Stuart Laycock’s collection of poetry from the Bosnian War

I singled out Stuart Laycock’s book for review because of an interest in its subject, the Bosnian War of the 1990s, around which I had written a poem and a stage-play. Though I did plenty of research, much of it stomach-heavingly painful even in the comfort of my armchair, Laycock’s collection puts me to shame in that I cannot say I was there, or indeed have been remotely close to any war zone, whereas, as proved by the stark and graphic photos he has included as a kind of extended centrefold to the book, he was right in the thick of the conflict, mourning the death of colleagues as he took part in seven aid missions to the country during the conflict. This biographical detail is not just a point of interest for the book’s blurb: it informs every line of every poem in this searing, deliberately underwritten collection.

Key to the overriding sense of dignified restraint is Laycock’s diction, as plain as everyday speech, often even less ornate than that, due to the way it reproduces the deadening effect of shock on the vocabulary of the war’s witnesses. A rare rhyming poem, ‘Sarajevo Cat’, is typical in another sense, that of the wry and invariably deadpan humour that runs through the collection:

The preceding poem is rather more characteristic of Laycock’s style, as it points out how though a lot of war reflects what happens in films in terms of fighting, explosions and death, there is also a good deal of humdrum routine and normality, or at least the illusion of it. ‘Split’ begins in apparent parody of Tennyson:

The town is desperately trying to hang on to its tourist status to the last, with people striding around in their sunshine clothes, while flowers grin from red baskets / and the only history is / Rome’s emperor Diocletian / who first built the place… Having achieved this form of ‘style indirect libre’ in conveying the locals’ efforts to focus attention on its points of historical interest, Laycock skilfully uses the simple word ‘but’ in order to catch their increasingly forced denials, as they try to suppress the realities:

Amidst the fruit and the flowers a little stall does sell tacky, metal war badges, but you don’t have to stop, . and the hotels on the outskirts are full of refugees but not here.Eventually though, the truth peeps through: And the war seems / a million miles distant, / until a UN helicopter / grey white against the / cyan sky briefly disturbs / the Spring chatter. Laycock’s ending is characteristically double-edged: But soon the interruption is gone. / God, I love this place. Sardonic as his tone appears to be, this place could of course also be the country itself, genuinely loved in the way anyone would come to love somewhere being ripped apart and violated before their very eyes.

Laycock often subtly emphasises the human and societal destruction behind the physical and architectural annihilation. In ‘Gone’, he surveys a lansdscape in which Each and every house / is burnt, destroyed, / gone, kicked over / by the war boots / of the last three years. There follows an instance of rare but potent metaphor:

The concept of a home – as in the song, so much more than just a house – being a living and therefore potentially a dead thing, is developed through the details within the building:

And the idea culminates in an ending which reminded me of Beckett’s Rockaby encapsulating the speaker’s utter loneliness by insisting on the lack of one other living soul:

Elsewhere, Laycock’s keenness of observation goes hand in hand with that same grim, unsentimental compassion and grief. An unforgettably downbeat elegy to his colleague Tony, one of two killed in the conflict, describes a funeral held on a spur / behind the hospital, punctuated by booms / in the background, which features Prayers in the air / and Last Post on a harmonica. Laycock’s final lines define the tone and style of his collection:

There is something marvellously human, and profoundly poet-like, if not ‘poetic’, about that Yep.

Other standout pieces include ‘”Tata!”, where a blinded boy with a shadow future repeatedly and heart-breakingly calls out for his father. The poem is brought to a shattering end by another of Laycock’s occasional but memorable metaphors, as we discover that sightlessness is not the boy’s only newly-inflicted blight:

But it’s not all dour and grey as a UN ‘copter. Several peoms are are not so much anthems for doomed youth as quiet celebrations of its resilience. ‘Kids’ in particular plays touchingly on the theme of reality versus illusion, with a portrayal of two boys engaged in war games in the midst of a very real war. One is toting a wooden toy Kalashnikov, but the other has a real olive-green, / scratched metal, cold steel / (unloaded I hope) / grenade launcher. That parenthetical crossing of fingers is amusingly repeated in the final stanza, which sums up so much of what Laycock has achieved in this uniquely authentic and heartfelt collection:

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, history, poetry reviews, year 2016 0 • Tags: books, history, Nick Cooke, poetry