Poetry review – TORMENTIL: Paul McDonald marvels that a tiny yellow flower has inspired so much fine poetry from Ian Humphreys

Tormentil

Ian Humphreys

Nine Arches Press.

ISBN: 978-1-913437-78-7

82pp £10.99

Tormentil

Ian Humphreys

Nine Arches Press.

ISBN: 978-1-913437-78-7

82pp £10.99

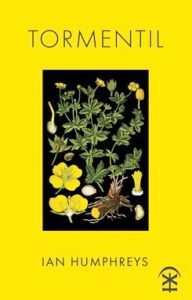

The stunning cover of Ian Humphrey’s new collection, Tormentil, makes it hard to miss. Indeed, it’s a rather lovely object, with an antique illustration of tormentil framed in vibrant chrome yellow. It’s the kind of book one props-up on the shelf with its cover facing outwards, like a photograph. It opens with the title poem, “Tormentil”, referencing the healing powers of this ‘tiny yellow flower’, aka ‘Bloodroot’, ‘Flesh and Blood’ and ‘Shepherds Knot’. It can be spotted growing in the West Yorkshire moorlands where the poet makes his home:

Up here, gold thread

creeps through boggy

peatland grass. Splashes

of sun under a dark sky.

Tormentil becomes a recurring, polysemic motif in the book, providing a ‘thread’ through many of these assured, sensitive and often humorous poems. They deal, among other things, with loss, memory, motherhood, identity, healing, and the significance of place, always with a sense of connection to the natural world. Sometimes this connection is as understated as the ‘tiny yellow flower’ itself. Attentive readers may see it in Humphreys’ use of colour in poems like “First signs”, which alludes to the early symptoms of dementia in a loved one who can no longer tell ‘saffron from salt’. It features too in his reference to his younger self as a “Wasp in a jam jar”, a poem about his desire to escape the toxic streets of his youth, ‘the forbidden boys / shirtless in glue-on scowls, torching a blown tyre / in the precinct’. Likewise, in “Firecrest”, Humphreys observes the plumage of birds ‘Yellow / as the wings / of goldfinches’ in the ‘parched/yellowing grass’. We see it also in the ‘sovereigns of light / across the pond’ in the poem “The sign language of trees”. Here both the colour and the dimensions of the golden coins echo the image of tormentil. It’s a poem about the sudden collapse of a tree, and what it might signify:

In the certainty of afternoon

one pale, severed limb

points towards the road to Pecket Well

I turn to look, shield my eyes.

A speaker who sees ‘certainty’ in an ‘afternoon’ is one who trusts in the ‘sign language’ of nature, and who’ll strive to interpret it. This is something we see throughout the book, as Humphreys reflects on life through the lens of nature. Sometimes this becomes an exploration of his own frailty, as in “Morning swim, 1979”, where he recalls spotting a water vole as a youngster, and contemplates throwing a stone at it ‘to show who is king’; sometimes it reflects his uncertainty, as in “tormentil +”, where he observes the four petals of the flower only to feel ‘lost / when a thousand compasses / guide the way’. But often the signs lead to more grounding and satisfying insights, as in “Cotton grass, late spring” where nature provides a place of solace for a speaker ‘lulled / by curlew song //l ike a newborn/adrift in / mother-rhythm’. The idea of nature as a mother is important to Humphreys, and he explores motherhood closely and lovingly. We see this in a piece like “Water brought me to you and it will sweep me away”, which ends:

When her baby falls asleep,

she lifts the child's soft-shelled mouth to her ear,

hears the ocean's

first word.

The natural world speaks through the newborn child, reinforcing the sense of continuity and connectivity in the poem, and in the book as a whole, which often reminds us that we are all children of nature. This idea of connection also feeds back to the tormentil image of the title poem: the yellow flower that spans the moors, weaving its parts together like a ‘gold thread’. Mother nature, like human mothers, has the capacity to heal, a notion that’s picked up again in the poem, “Mouse-ear hawkweed”, focusing on another ‘yellow-headed plant’ that’s ‘more like a small dandelion’ than a tormentil:

Yet this too is known for healing wounds.

What is it about tiny yellow flowers?

The way they scatter through spring grass,

a thin gauze of lemon magic. If only

there were enough of them to swathe

the earth. To close the lips. To hush

the hushed scream. But no –

I think instead of a woman’s lips

pressed against a child’s red-raw shin.

The sharpness of that pebble beach.

Hythe, 1970. I’m there, there, there.

The healing qualities of nature parallel the healing instincts of a mother: both have the power ‘To hush / the hushed scream’: while the source of the ‘magic’, both in nature, and the poet’s mother, remains elusive, we can’t help sensing connections between them.

One of the stand-out poems for me is another depicting the memory of a mother, “The Rochdale Canal”. Here the speaker recalls walking along the canal with his mother as she urges her son to ‘look at the colours’; she is another nurturing mother, who ‘slipped breaded scampi from’ her plate onto his, sharing her ‘good luck with the family’. Again nature is central to the experience, as the two of them observe ‘the first slip of water over wood at Lock 11’:

It can take an eternity to fill a void. Look at the ferns thriving

deep in the chamber wall, how they hold firm,

soft fingers outstretched, drowned, until the flood recedes

and the sun revives them. I remember your love

for these painted narrowboats, the way they garland

the canal bank like festival lanterns. Listen

to the jackdaws, slipping and tumbling above

the old mill chimney, their laughter echoing

in its throat. But where is our kingfisher?

She must be close, waiting to slip from a willow tree,

to swoop and sip her bright blue reflection.

The ‘soft fingers’ of the ferns in the lock are ‘outstretched’ almost like a child’s, reaching for help in the flooded chamber, until the lock empties and the nurturing light of ‘the sun revives them’. The idea of a connection between nature, mother and son is strengthened with delightful subtlety at the end by the phrase ‘our kingfisher’, where the possessive determiner, ‘our’, links all three.

We should never judge books by their covers, of course, but to say this one is as good as it looks is a compliment of the highest order. The gorgeous design promises much, and Humphreys delivers in abundance. It brims with so much life that, if it didn’t look so good on my bookshelf, I’d be tempted to plant it in the garden, certain I’d wake one morning to a carpet of yellow petals: ‘Splashes of sun under a dark sky’.

Oct 20 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Ian Humphreys

Poetry review – TORMENTIL: Paul McDonald marvels that a tiny yellow flower has inspired so much fine poetry from Ian Humphreys

The stunning cover of Ian Humphrey’s new collection, Tormentil, makes it hard to miss. Indeed, it’s a rather lovely object, with an antique illustration of tormentil framed in vibrant chrome yellow. It’s the kind of book one props-up on the shelf with its cover facing outwards, like a photograph. It opens with the title poem, “Tormentil”, referencing the healing powers of this ‘tiny yellow flower’, aka ‘Bloodroot’, ‘Flesh and Blood’ and ‘Shepherds Knot’. It can be spotted growing in the West Yorkshire moorlands where the poet makes his home:

Tormentil becomes a recurring, polysemic motif in the book, providing a ‘thread’ through many of these assured, sensitive and often humorous poems. They deal, among other things, with loss, memory, motherhood, identity, healing, and the significance of place, always with a sense of connection to the natural world. Sometimes this connection is as understated as the ‘tiny yellow flower’ itself. Attentive readers may see it in Humphreys’ use of colour in poems like “First signs”, which alludes to the early symptoms of dementia in a loved one who can no longer tell ‘saffron from salt’. It features too in his reference to his younger self as a “Wasp in a jam jar”, a poem about his desire to escape the toxic streets of his youth, ‘the forbidden boys / shirtless in glue-on scowls, torching a blown tyre / in the precinct’. Likewise, in “Firecrest”, Humphreys observes the plumage of birds ‘Yellow / as the wings / of goldfinches’ in the ‘parched/yellowing grass’. We see it also in the ‘sovereigns of light / across the pond’ in the poem “The sign language of trees”. Here both the colour and the dimensions of the golden coins echo the image of tormentil. It’s a poem about the sudden collapse of a tree, and what it might signify:

A speaker who sees ‘certainty’ in an ‘afternoon’ is one who trusts in the ‘sign language’ of nature, and who’ll strive to interpret it. This is something we see throughout the book, as Humphreys reflects on life through the lens of nature. Sometimes this becomes an exploration of his own frailty, as in “Morning swim, 1979”, where he recalls spotting a water vole as a youngster, and contemplates throwing a stone at it ‘to show who is king’; sometimes it reflects his uncertainty, as in “tormentil +”, where he observes the four petals of the flower only to feel ‘lost / when a thousand compasses / guide the way’. But often the signs lead to more grounding and satisfying insights, as in “Cotton grass, late spring” where nature provides a place of solace for a speaker ‘lulled / by curlew song //l ike a newborn/adrift in / mother-rhythm’. The idea of nature as a mother is important to Humphreys, and he explores motherhood closely and lovingly. We see this in a piece like “Water brought me to you and it will sweep me away”, which ends:

When her baby falls asleep, she lifts the child's soft-shelled mouth to her ear, hears the ocean's first word.The natural world speaks through the newborn child, reinforcing the sense of continuity and connectivity in the poem, and in the book as a whole, which often reminds us that we are all children of nature. This idea of connection also feeds back to the tormentil image of the title poem: the yellow flower that spans the moors, weaving its parts together like a ‘gold thread’. Mother nature, like human mothers, has the capacity to heal, a notion that’s picked up again in the poem, “Mouse-ear hawkweed”, focusing on another ‘yellow-headed plant’ that’s ‘more like a small dandelion’ than a tormentil:

The healing qualities of nature parallel the healing instincts of a mother: both have the power ‘To hush / the hushed scream’: while the source of the ‘magic’, both in nature, and the poet’s mother, remains elusive, we can’t help sensing connections between them.

One of the stand-out poems for me is another depicting the memory of a mother, “The Rochdale Canal”. Here the speaker recalls walking along the canal with his mother as she urges her son to ‘look at the colours’; she is another nurturing mother, who ‘slipped breaded scampi from’ her plate onto his, sharing her ‘good luck with the family’. Again nature is central to the experience, as the two of them observe ‘the first slip of water over wood at Lock 11’:

The ‘soft fingers’ of the ferns in the lock are ‘outstretched’ almost like a child’s, reaching for help in the flooded chamber, until the lock empties and the nurturing light of ‘the sun revives them’. The idea of a connection between nature, mother and son is strengthened with delightful subtlety at the end by the phrase ‘our kingfisher’, where the possessive determiner, ‘our’, links all three.

We should never judge books by their covers, of course, but to say this one is as good as it looks is a compliment of the highest order. The gorgeous design promises much, and Humphreys delivers in abundance. It brims with so much life that, if it didn’t look so good on my bookshelf, I’d be tempted to plant it in the garden, certain I’d wake one morning to a carpet of yellow petals: ‘Splashes of sun under a dark sky’.