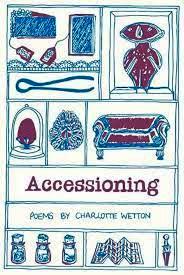

Poetry review – ACCESSIONING: Emma Storr considers Charlotte Wetton’s poems on the importance of remembering

Accessioning

Charlotte Wetton

Emma Press 2023

ISBN 9 781915628138

30pp £7.00

Accessioning

Charlotte Wetton

Emma Press 2023

ISBN 9 781915628138

30pp £7.00

Charlotte Wetton’s latest pamphlet Accessioning is a fascinating exploration of how we curate and categorise objects and people, past and present. Her poems often challenge the reductive process of curation by introducing the surreal, or highlighting the role of the imagination, uncontained and free.

The first poem in the book, “Scream”, describes the alienation of living in the modern world. The poem opens:

Thank God for the MOT expiring

and the tax-return deadline

and open windows we must rush to close against the rain

The wide irregular spaces between lines add to the sense of liminality expressed by the speaker. The second stanza is more directive:

Go to places that demand perfunctory exchanges

drive-thrus, petrol stations

where our lines are mapped

and it’s all a bad acting gig, unpaid.

The poem imagines what the scream pent up inside might sound and look like in a series of striking metaphors:

a tsunami

an opera roiling out

a tent of red noise

unravelled

flaming over the land.

In “Commissioning a Map”, we know things are not going to go well right from the start because ‘The cartographer and I have had a tiff:’ Wetton has great fun playing with ideas about boundaries, distances and scale. As the speaker points out:

I want the bridleways unbridled,

the best bacon sandwiches mapped,

where to go sledging and

what time not to walk alone at night.

Lyricism is evident when we are told the cartographer ‘has plotted the silence of the moors / (marsh, reeds or saltings) / and the gorgeous swoop of the motorway.’

“The Archivist’s House” is a sad poem about a man who has listed, filed, catalogued and indexed his life, categorised under titles such as ‘Film Releases Missed’ and ‘Unfinished Conversations’. The image of ‘thickets of possibles choke up the passageways’ paints a clear picture of clutter in his house. The shape of the poem does something similar. Dropped lines and stacked words mirror the extensive box files ‘spongy and bulging’ and the ‘rustling pages’ spilling out of pigeon holes. We also get to feel and smell this environment in the ‘wadded heaps / pressed into mulch’ and ‘the fusty smell of his paper skins’. The poem is crafted meticulously to convey pathos and to make us question how and why we file our lives.

Wetton travels to Greece, South Africa and Devon to explore places where objects have been acquisitioned and placed in drawers or glass cases for inspection. In “What’s Left? Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens,” she makes full use of the rich vocabulary used to describe different sacred objects buried with the dead:

Grave goods

ayrballoi

bucranium

core of obsidian

The clay figures placed beside the bodies might be:

mortals or mythological beings

of probable apotropaic

character

divine escorts to the dead

(Apotropaic means providing protection against harm, evil or malevolent spirits.)

In South Africa, it is slaves from the past that are curated, their names forming a tall perspex column. The historians involved ‘pick up a white man’s story squeeze it harder’ to find a bequest of household objects to a black female. The list of names provided in italic script confers dignity on these unsung victims and sometimes references their country of origin. As the speaker says:

the historians are clothing the stripped

their coat-hanger names

Great care is also taken by the curators at the Manchester museum who are assembling a sloth skeleton: ‘he is fretwork / unfleshed / an armful of air ’. This delightful poem celebrates the exhibit and bemoans the loss of the living creature in its own habitat when the curators:

tongue his soft name

sibilant hiss of Eden,

thick plummet of felled forest

his muzzle turned to the wall.

You can memorialise the living as well as the dead, a point made by Wetton in her short poem “I Spit Cherry Stones into the Sea” in which she takes photographs to ‘curate / myself to myself’ on her trip to Nafplion.

The final poem in the pamphlet “When This is Over We’ll Memorialise” makes uncomfortable reading as it lists the many sea creatures that have been captured or killed as well as the humans attacked by sharks or whales. Mourning is common to both animal and human in this context. We all need ‘love and attachment’ and suffer when our families are ‘decimated’.

Accessioning is a pamphlet of great variety around the theme of memorialisation and curation, explored with craft and wit. I enjoyed reading it tremendously.

Oct 23 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Charlotte Wetton

Poetry review – ACCESSIONING: Emma Storr considers Charlotte Wetton’s poems on the importance of remembering

Charlotte Wetton’s latest pamphlet Accessioning is a fascinating exploration of how we curate and categorise objects and people, past and present. Her poems often challenge the reductive process of curation by introducing the surreal, or highlighting the role of the imagination, uncontained and free.

The first poem in the book, “Scream”, describes the alienation of living in the modern world. The poem opens:

Thank God for the MOT expiring and the tax-return deadline and open windows we must rush to close against the rainThe wide irregular spaces between lines add to the sense of liminality expressed by the speaker. The second stanza is more directive:

Go to places that demand perfunctory exchanges drive-thrus, petrol stations where our lines are mapped and it’s all a bad acting gig, unpaid.The poem imagines what the scream pent up inside might sound and look like in a series of striking metaphors:

a tsunami an opera roiling out a tent of red noise unravelled flaming over the land.In “Commissioning a Map”, we know things are not going to go well right from the start because ‘The cartographer and I have had a tiff:’ Wetton has great fun playing with ideas about boundaries, distances and scale. As the speaker points out:

Lyricism is evident when we are told the cartographer ‘has plotted the silence of the moors / (marsh, reeds or saltings) / and the gorgeous swoop of the motorway.’

“The Archivist’s House” is a sad poem about a man who has listed, filed, catalogued and indexed his life, categorised under titles such as ‘Film Releases Missed’ and ‘Unfinished Conversations’. The image of ‘thickets of possibles choke up the passageways’ paints a clear picture of clutter in his house. The shape of the poem does something similar. Dropped lines and stacked words mirror the extensive box files ‘spongy and bulging’ and the ‘rustling pages’ spilling out of pigeon holes. We also get to feel and smell this environment in the ‘wadded heaps / pressed into mulch’ and ‘the fusty smell of his paper skins’. The poem is crafted meticulously to convey pathos and to make us question how and why we file our lives.

Wetton travels to Greece, South Africa and Devon to explore places where objects have been acquisitioned and placed in drawers or glass cases for inspection. In “What’s Left? Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens,” she makes full use of the rich vocabulary used to describe different sacred objects buried with the dead:

Grave goods ayrballoi bucranium core of obsidian The clay figures placed beside the bodies might be: mortals or mythological beings of probable apotropaic character divine escorts to the dead(Apotropaic means providing protection against harm, evil or malevolent spirits.)

In South Africa, it is slaves from the past that are curated, their names forming a tall perspex column. The historians involved ‘pick up a white man’s story squeeze it harder’ to find a bequest of household objects to a black female. The list of names provided in italic script confers dignity on these unsung victims and sometimes references their country of origin. As the speaker says:

the historians are clothing the stripped their coat-hanger namesGreat care is also taken by the curators at the Manchester museum who are assembling a sloth skeleton: ‘he is fretwork / unfleshed / an armful of air ’. This delightful poem celebrates the exhibit and bemoans the loss of the living creature in its own habitat when the curators:

You can memorialise the living as well as the dead, a point made by Wetton in her short poem “I Spit Cherry Stones into the Sea” in which she takes photographs to ‘curate / myself to myself’ on her trip to Nafplion.

The final poem in the pamphlet “When This is Over We’ll Memorialise” makes uncomfortable reading as it lists the many sea creatures that have been captured or killed as well as the humans attacked by sharks or whales. Mourning is common to both animal and human in this context. We all need ‘love and attachment’ and suffer when our families are ‘decimated’.

Accessioning is a pamphlet of great variety around the theme of memorialisation and curation, explored with craft and wit. I enjoyed reading it tremendously.