Claudette Johnson’s exhibition Presence is on at the Courtauld until 14 January 2024.

Johnson first came to attention in 1982 while a student at The Polytechnic Wolverhampton. Britain’s ‘black cultural renaissance’ began, not in the famous institutions of London but in the Polytechs of the north: Wolverhampton, Trent, Sunderland. In 1982, the recently formed BLK Art Group organised the First National Black Art convention at Wolverhampton. At this conference Johnson demanded recognition and space for Black women. To talk only about racism was not enough ‘the black woman experiences oppression on the grounds of her sex, sexuality AND race… a Black woman [has] a history and struggle of her own.’

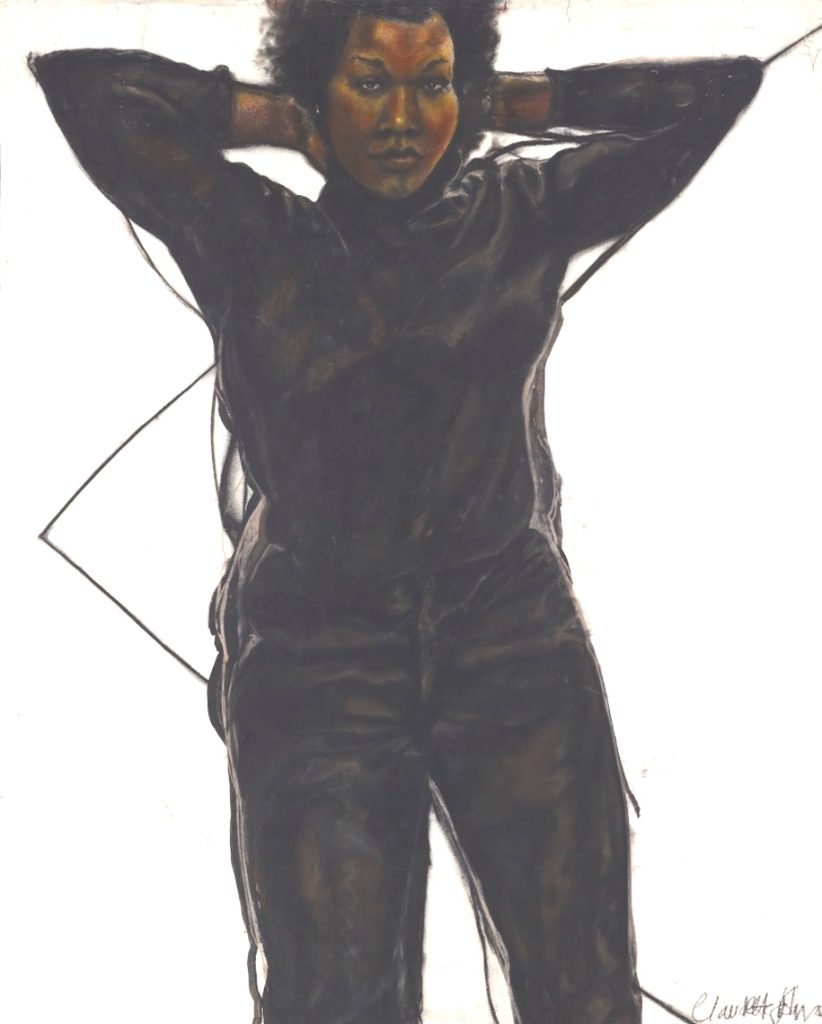

Since 1982 Johnson has made the ‘presence’ of Black women the primary subject of her work. The subjects are ‘monoliths’, larger than life depictions of women. They not only occupy the entire canvas but continue beyond it, entering the world and staying there. Their direct gaze interrogates the viewer. She said she aimed to make Black women visible in society whilst creating depictions of the Black female body that resisted objectification. Eddie Chambers remembered seeing them for the first time – and realising that what you gave these women was respect.

Claudette Johnson, Part of Trilogy, 1982-86

There was a general feeling in the 80s that feminist art historians and curators had evaded issues of race and that it was up to Black women artists to remedy this. As a result of the Wolverhampton conference a network of Black women artists developed. Lubaina Himid curated three exhibitions in London – Five Black Women at the Africa Centre (1983), Black Women Time Now at Battersea Arts Centre (1983-4) and The Thin Black Line at the Institute for Contemporary Arts (1985). However, Johnson notes that notes that the ICA exhibition was in the corridors and stairwells not the gallery spaces themselves…

These exhibitions established the importance of the women’s work but in the 1990s it was black male artists who were getting the attention. Teaching in the early 21st Century I was hard pressed to get images and information about the women involved in these early exhibitions. Himid has talked about this time as the ‘wilderness years’ and Johnson said of herself it ‘was the beginning of the slide into obscurity ‘. She had two sons and no studio. She taught. This is such a woman’s story. However, the network continued and in 2014 Himid invited her to exhibit again. She said, ‘I’ve been thinking about the way you make your marks, and I want to see it again’. I like this description – the mark making – and yes, the surety of line is so important in Johnson’s work. It struck me again, viewing this exhibition, how assured it is, how much in control of her media she is.

Claudette Johnson, Reclining Figure, 2017, Gouache and pastel on paper, 113 x 257 cm

She’s not afraid to let the line be all there is. There is an almost threadbare look that somehow manages enormous solidity and generosity. The lines are both delicate and strong. I feel sated by this painting somehow, as though it was what I had been waiting for. The deep, sumptuous blue gouache, the touches of red, are enough to anchor her as she floats in her own space. I am not privy to her thoughts because they don’t involve me and that’s the way it should be. She isn’t a women prepared for viewing but wears her own life. She anchors me too – as though I could lie like this, taking up that space, being the person I want to be.

Johnson’s return in a solo exhibition at Modern Art Oxford in 2019 was welcome. Her images were as strong as ever as she looked over her shoulder at twentieth century modernism.

Claudette Johnson, Standing Figure with African Masks, 2018, Pastels and gouache on paper, 163 x 133 cm.

The expression is weary. ‘How long?’ she seems to say – primitivism, colonialism, sexploitation of Black women. This is what you want me to say and I’m saying it but please…here I am, this is me. The Courtauld is an interesting venue for her present exhibition; you feel she’s got a beady eye on the Gauguin’s a few doors away.

There are paintings of Black men now in checked shirts, buttoned up to the neck in colour; or lying stranded on a sea of blue, but it is still the women who dominate. The poster image is Figure in Blue,2018, the model an artist friend who has been the subject of several paintings. Again, she inhabits her own world, a swirl of colour ebbing and flowing around her; the colour is seductive but she remains herself. The way Johnson lays the gouache down in rich opaque surfaces reminds me of Frances Hodgkins’s late paintings, the same vivid use of gouache but here more real, more weighted with the world.

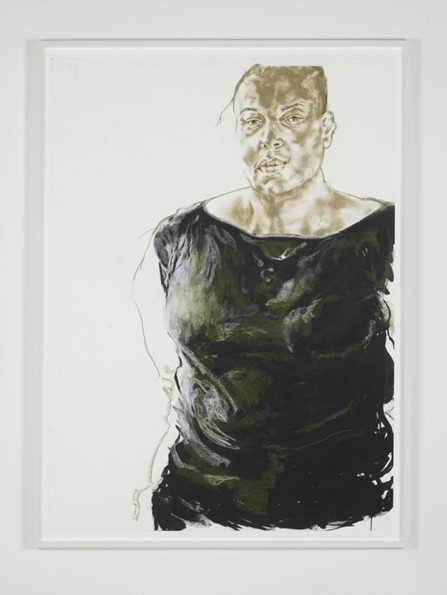

The painting I kept going back to had no seductive colour – a woman in a black dress simply looking at the viewer.

I felt a jolt of recognition. Here is someone who has traversed the world and knows it but is not afraid of it. It just lies there in her consciousness like a stain. The world breaks over her but will not dislodge her. Here we claim the right to stand unbroken.

Jenny Vuglar © 2023.

Claudette Johnson’s exhibition Presence is on at the Courtauld until 14 January 2024.

Johnson first came to attention in 1982 while a student at The Polytechnic Wolverhampton. Britain’s ‘black cultural renaissance’ began, not in the famous institutions of London but in the Polytechs of the north: Wolverhampton, Trent, Sunderland. In 1982, the recently formed BLK Art Group organised the First National Black Art convention at Wolverhampton. At this conference Johnson demanded recognition and space for Black women. To talk only about racism was not enough ‘the black woman experiences oppression on the grounds of her sex, sexuality AND race… a Black woman [has] a history and struggle of her own.’

Since 1982 Johnson has made the ‘presence’ of Black women the primary subject of her work. The subjects are ‘monoliths’, larger than life depictions of women. They not only occupy the entire canvas but continue beyond it, entering the world and staying there. Their direct gaze interrogates the viewer. She said she aimed to make Black women visible in society whilst creating depictions of the Black female body that resisted objectification. Eddie Chambers remembered seeing them for the first time – and realising that what you gave these women was respect.

Claudette Johnson, Part of Trilogy, 1982-86

There was a general feeling in the 80s that feminist art historians and curators had evaded issues of race and that it was up to Black women artists to remedy this. As a result of the Wolverhampton conference a network of Black women artists developed. Lubaina Himid curated three exhibitions in London – Five Black Women at the Africa Centre (1983), Black Women Time Now at Battersea Arts Centre (1983-4) and The Thin Black Line at the Institute for Contemporary Arts (1985). However, Johnson notes that notes that the ICA exhibition was in the corridors and stairwells not the gallery spaces themselves…

These exhibitions established the importance of the women’s work but in the 1990s it was black male artists who were getting the attention. Teaching in the early 21st Century I was hard pressed to get images and information about the women involved in these early exhibitions. Himid has talked about this time as the ‘wilderness years’ and Johnson said of herself it ‘was the beginning of the slide into obscurity ‘. She had two sons and no studio. She taught. This is such a woman’s story. However, the network continued and in 2014 Himid invited her to exhibit again. She said, ‘I’ve been thinking about the way you make your marks, and I want to see it again’. I like this description – the mark making – and yes, the surety of line is so important in Johnson’s work. It struck me again, viewing this exhibition, how assured it is, how much in control of her media she is.

Claudette Johnson, Reclining Figure, 2017, Gouache and pastel on paper, 113 x 257 cm

She’s not afraid to let the line be all there is. There is an almost threadbare look that somehow manages enormous solidity and generosity. The lines are both delicate and strong. I feel sated by this painting somehow, as though it was what I had been waiting for. The deep, sumptuous blue gouache, the touches of red, are enough to anchor her as she floats in her own space. I am not privy to her thoughts because they don’t involve me and that’s the way it should be. She isn’t a women prepared for viewing but wears her own life. She anchors me too – as though I could lie like this, taking up that space, being the person I want to be.

Johnson’s return in a solo exhibition at Modern Art Oxford in 2019 was welcome. Her images were as strong as ever as she looked over her shoulder at twentieth century modernism.

Claudette Johnson, Standing Figure with African Masks, 2018, Pastels and gouache on paper, 163 x 133 cm.

The expression is weary. ‘How long?’ she seems to say – primitivism, colonialism, sexploitation of Black women. This is what you want me to say and I’m saying it but please…here I am, this is me. The Courtauld is an interesting venue for her present exhibition; you feel she’s got a beady eye on the Gauguin’s a few doors away.

There are paintings of Black men now in checked shirts, buttoned up to the neck in colour; or lying stranded on a sea of blue, but it is still the women who dominate. The poster image is Figure in Blue,2018, the model an artist friend who has been the subject of several paintings. Again, she inhabits her own world, a swirl of colour ebbing and flowing around her; the colour is seductive but she remains herself. The way Johnson lays the gouache down in rich opaque surfaces reminds me of Frances Hodgkins’s late paintings, the same vivid use of gouache but here more real, more weighted with the world.

The painting I kept going back to had no seductive colour – a woman in a black dress simply looking at the viewer.

I felt a jolt of recognition. Here is someone who has traversed the world and knows it but is not afraid of it. It just lies there in her consciousness like a stain. The world breaks over her but will not dislodge her. Here we claim the right to stand unbroken.

Jenny Vuglar © 2023.

By Jenny Vuglar • art, exhibitions, painting, year 2023 • Tags: art, exhibitions, Jenny Vuglar, painting