Poetry review – WHEN ILIUM BURNS: Charles Rammelkamp enjoys unravelling a perplexing narrative sequence by Tiffany Troy

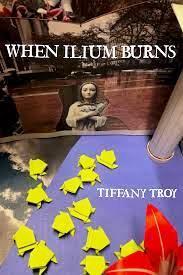

When Ilium Burns

Tiffany Troy

Bottlecap Press, 2022

44 pages $10.00

When Ilium Burns

Tiffany Troy

Bottlecap Press, 2022

44 pages $10.00

Given the names of the characters in Tiffany Troy’s poetry chapbook, When Ilium Burns – Master, Friend, Nurse, etc. – one is tempted to think of this collection as an allegory, like Everyman or like Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, Orwell’s Animal Farm. If so, what is the moral, the lesson? What’s the hidden meaning?

The subversive protagonist of Tiffany Troy’s seamlessly interconnected weave of poems is in perpetual conflict with the ruthless character called Master; she oscillates between an infinite resignation and a sort of hopeful rebellion that involves “playing the system” as much as it does blowing it up. Ilium will burn but who will light the match? More to the point, who will be the Aeneas that resurrects the burnt-down empire? Could it be Master, whom we first meet in the poem, “The Wooden Yamaha,” who tells the protagonist, “Without money, there is no dignity,” and whom we later learn in “Wedding-bound Million Dollar Dream,” harbors dreams of “resuscitating a lost dynasty”? We also learn in “Somnium Iliacus”

Master dreams of empire in the United States

where he would make a name for himself.

Master obviously dreams big! The world is his stage. Master is overbearing and cruel, an overwhelming adversary. In “Holy Saturday,” the protagonist tells us “Master keeps a running tab of my infractions.” We read in “This” that

All I want is for him to stop

and leave me alone in the self-hate

he has so successfully cultivated

The protagonist appears to be suffering from the “Stockholm Syndrome,” a coping mechanism in which an abused person develops an almost worshipful attitude toward the tormentor. In the poem, “At My Trial,” she confesses:

Master texts me, when you are striving for the better,

I will always be with you. Master lies to me when he says

I miss you. I learned to love his lies.

The protagonist/speaker may or may not be “Baby Tiger,” who appears in two poems, “The Queen of England” and “Notes on the word ‘impossible.’” In the second of these, Baby Tiger speaks directly to the reader in the first person, as does the protagonist – the character tormented and dominated by Master – in almost all of the others. Baby Tiger is a lawyer. In “The Queen of England” Baby Tiger declares, “I’m the most relaxed attorney you’ll find.” Her adversary – another attorney representing different interests? – responds with sarcastic irony, “If you are relaxed, then I’m the Queen of England.” But the name certainly suggests a fierce competitor, somebody who doesn’t give up.

While the protagonist and Master are in conflict with each other, they also depend on one another. They work together like “Tongue and Teeth,” an implicitly violent image. “Mama says Master and I / are like tongue and teeth,” she tells us. The poem goes on:

The tongue and teeth must

work together.

We are

always together.

My arm is hurting, you say,

I do not see

the indigo blue

where his fingers held

your right arm.

Master when he beats me keeps

saying I’m sick.

Master, who, as the name suggests, is a dominant and domineering person, certainly dominates the stage, appearing in eleven of the seventeen poems that make up When Ilium Burns. But as in other allegories, there are also more sympathetic characters. One of these is called “Friend.” In “Sweet Clementine” she writes: “Friend and I invented a hand signal for slitting our throats” – in response to Master’s “wrath.” (“I expect Master’s body quivering with want to beat me. / I taunt him to hit me….”)

The Friend, who is a doctor (doctors and lawyers figure big in the drama) – “a kind Friend and a cold Doctor” – bears a certain resemblance to Master: “Her Friend cursed just like Master / who planned the future with Odyssean cunning.” Friend works hand-in-glove with his sidekick, Nurse. “A Thank You Card” begins:

The Friend told the Nurse that he believed in her

in the lengthy walk

they took along the river:

How could you think of me as duplicitous?

Beware of friends!

While metaphorically taking place in ancient myth, as in many allegorical settings, so much of the conflict here occurs in a very real New York, in the Flushing neighborhood of Queens, which may be the key to the allegory: America, the behemoth, the ultimate adversary. It grinds you down with its bureaucracy and legal procedures. Troy writes in “Queen of England”: “As Baby Tiger, I often deal with impossible adversaries.”

Tiffany Troy, who is the Managing Editor of Tupelo Quarterly, may also be playing on her name. Ilium is the ancient name for Troy, after all. (It’s also part of the hip bone.) She has called When Ilium Burns a “bildungsroman,” the German term for a novel that is a “coming of age” story, dealing with a character’s formative years, which hints at the protagonist’s struggles growing up.

In that light, we come back to the question, what does the allegory mean? The answer may be in the final poem of the collection, the resolution to all this struggle. Titled “The Hike,” the poem dwells indeed on “the journey” – metaphor for life – and is written in an aspirational tone. It concludes:

May we walk back to where the water buffalo roamed

that the golden dog from our childhoods

might save us still from being scattered across

this country, vast as an entire world.

May we hike up a different mountain,

that among the forest of birch trees,

beyond boulders as tall as our waists,

light might still grace our faces.

The idea is to persevere in pursuit of your dreams, despite the overwhelming odds, the daunting circumstances. Nobody can stop you but you.

Feb 11 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Tiffany Troy

Poetry review – WHEN ILIUM BURNS: Charles Rammelkamp enjoys unravelling a perplexing narrative sequence by Tiffany Troy

Given the names of the characters in Tiffany Troy’s poetry chapbook, When Ilium Burns – Master, Friend, Nurse, etc. – one is tempted to think of this collection as an allegory, like Everyman or like Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, Orwell’s Animal Farm. If so, what is the moral, the lesson? What’s the hidden meaning?

The subversive protagonist of Tiffany Troy’s seamlessly interconnected weave of poems is in perpetual conflict with the ruthless character called Master; she oscillates between an infinite resignation and a sort of hopeful rebellion that involves “playing the system” as much as it does blowing it up. Ilium will burn but who will light the match? More to the point, who will be the Aeneas that resurrects the burnt-down empire? Could it be Master, whom we first meet in the poem, “The Wooden Yamaha,” who tells the protagonist, “Without money, there is no dignity,” and whom we later learn in “Wedding-bound Million Dollar Dream,” harbors dreams of “resuscitating a lost dynasty”? We also learn in “Somnium Iliacus”

Master obviously dreams big! The world is his stage. Master is overbearing and cruel, an overwhelming adversary. In “Holy Saturday,” the protagonist tells us “Master keeps a running tab of my infractions.” We read in “This” that

The protagonist appears to be suffering from the “Stockholm Syndrome,” a coping mechanism in which an abused person develops an almost worshipful attitude toward the tormentor. In the poem, “At My Trial,” she confesses:

The protagonist/speaker may or may not be “Baby Tiger,” who appears in two poems, “The Queen of England” and “Notes on the word ‘impossible.’” In the second of these, Baby Tiger speaks directly to the reader in the first person, as does the protagonist – the character tormented and dominated by Master – in almost all of the others. Baby Tiger is a lawyer. In “The Queen of England” Baby Tiger declares, “I’m the most relaxed attorney you’ll find.” Her adversary – another attorney representing different interests? – responds with sarcastic irony, “If you are relaxed, then I’m the Queen of England.” But the name certainly suggests a fierce competitor, somebody who doesn’t give up.

While the protagonist and Master are in conflict with each other, they also depend on one another. They work together like “Tongue and Teeth,” an implicitly violent image. “Mama says Master and I / are like tongue and teeth,” she tells us. The poem goes on:

Master, who, as the name suggests, is a dominant and domineering person, certainly dominates the stage, appearing in eleven of the seventeen poems that make up When Ilium Burns. But as in other allegories, there are also more sympathetic characters. One of these is called “Friend.” In “Sweet Clementine” she writes: “Friend and I invented a hand signal for slitting our throats” – in response to Master’s “wrath.” (“I expect Master’s body quivering with want to beat me. / I taunt him to hit me….”)

The Friend, who is a doctor (doctors and lawyers figure big in the drama) – “a kind Friend and a cold Doctor” – bears a certain resemblance to Master: “Her Friend cursed just like Master / who planned the future with Odyssean cunning.” Friend works hand-in-glove with his sidekick, Nurse. “A Thank You Card” begins:

Beware of friends!

While metaphorically taking place in ancient myth, as in many allegorical settings, so much of the conflict here occurs in a very real New York, in the Flushing neighborhood of Queens, which may be the key to the allegory: America, the behemoth, the ultimate adversary. It grinds you down with its bureaucracy and legal procedures. Troy writes in “Queen of England”: “As Baby Tiger, I often deal with impossible adversaries.”

Tiffany Troy, who is the Managing Editor of Tupelo Quarterly, may also be playing on her name. Ilium is the ancient name for Troy, after all. (It’s also part of the hip bone.) She has called When Ilium Burns a “bildungsroman,” the German term for a novel that is a “coming of age” story, dealing with a character’s formative years, which hints at the protagonist’s struggles growing up.

In that light, we come back to the question, what does the allegory mean? The answer may be in the final poem of the collection, the resolution to all this struggle. Titled “The Hike,” the poem dwells indeed on “the journey” – metaphor for life – and is written in an aspirational tone. It concludes:

The idea is to persevere in pursuit of your dreams, despite the overwhelming odds, the daunting circumstances. Nobody can stop you but you.