Poetry review – COLLECTED POEMS: Emma Lee surveys Anne Stevenson‘s illustrious career as

summed up in a new compilation of her work

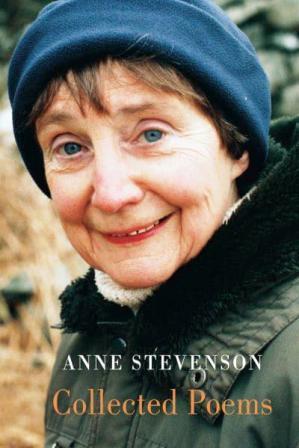

Collected Poems

Anne Stevenson

Bloodaxe

ISBN 9781780376516

560pp £25

Collected Poems

Anne Stevenson

Bloodaxe

ISBN 9781780376516

560pp £25

This substantial volume of poems by Anne Stevenson (1933-2020) is drawn from collections beginning with Living in America (1965) and going up to Completing the Circle (2020). Stevenson was a contemporary of Plath and, like Plath, was an American who married an Englishman and came to settle in England (in 1962 for Stevenson). This is both as much and as little as they had in common. Stevenson was a quiet poet, writing and publishing accomplished poems without much fanfare. She was generous in workshops and in support of other poets and will always be remembered fondly. Stevenson frequently revised and recycled poems so some poems have been cut from selections of books where they originally appeared in favour of the latest version in the most recent collection. One of the earliest poems is, ‘The Traveller’ (1961),

Outside the rain began to fall

While pieces of a yellow tree

Broke off and smashed like pottery,

I watched them drop, I ate, I rose,

I looked beneath my hair. I froze.

My ghosts were standing there in rows.

To the narrator, this is an ordinary scene. There’s a meal not worth describing, autumnal weather and she notes the leaves dropping under the weight of rain until she stands, presumably checks to she’s not left anything behind, and sees her ghosts. We get to meet some of them. There are also reflections on life from someone used to observing, not being centre stage but directing from the wings. ‘The Mother’ (complete, from Reversals, 1970) personifies this,

Of course I love them, they are my children.

That is my daughter and this is my son.

And this is the life I give them to please them.

It has never been used. Keep it safe, pass it on.

The children are loved but there’s also a sense of conflict: the mother is self-less, living for her children and making sacrifices for them by putting them first over her own wants and needs. There’s a second conflict where she acknowledges the life she wants for them may not be the life they want. She asks for it to be passed on. Family life dominates Correspondences A Family History in Letters (1974) which takes letters, journal fragments, newspaper excerpts from members of the imagined Chandler Family through six generations from 1829 to 1972. This is a volume that takes readers outside the poet’s life as the poems lay out family frictions and desires achieved or thwarted through connection.

The maintenance of connection and reputation is picked up again in ‘Respectable House’ (from Enough of Green, 1977) which ends

Push open the door. More. And a little more.

You seem to be welcome. You can't help stepping inside.

You see how light and its residents have lied.

You see what the gun on the table has to be used for.

Behind the façade of respectability lies menace, the threats needed to keep family members in line, lest any entertain the idea of washing the family’s dirty linen in public. Stevenson’s poems may be domestic in subject, but all life is here, and she lifts the veneers of respectability and reputation to prod at the darkness beneath.

Art, specifically poetry, is another subject. In ‘Making Poetry’ (from The Fiction-Makers, 1985), she suggests poets

embark on voyages over voices,

evade the ego-hill, the misery-well,

the siren hiss of publish, success, publish,

success, success, success.

And why inhabit, make, inherit poetry?

There’s no simple answer, but the poem suggests, it’s “one of those haunted, undefendable, unpoetic/ crosses we have to find.”

The poems from ‘The Other House’ were written around the time Stevenson wrote Bitter Fame, which is outside the scope of this review. ‘The Other House’ includes three poems for Sylvia Plath. In ‘Letter to Sylvia Plath’, Stevenson writes,

Three springs you've perched like a black rook

between sweet weather and my mind.

At last I have to seem unkind

and exorcise my awkward awe.

My shoulder doesn't like your claw.

I understand that writing a biography can feel as if your subject has taken you over, that you are inhabiting their life. However, the subject didn’t chose the biographer or to have to have the biography written so it seems an odd image that Plath was perched on the biographer’s shoulder, particularly in light of Stevenson talking about writing Bitter Fame as if Olwyn Hughes was looking over her shoulder. This was the biography that Hughes wanted to “set the record straight” and was the only one she was prepared to authorise. The poem ends,

We learn to be human when we kneel

to imagination, which is real

long after reality is dead

and history has put its bones to bed.

Sylvia, you have won at last,

embodying the living past,

catching the anguish of your age

in accents of a private rage.

It seems the biographer was in awe of her subject’s skills but not empathetic to her as a person.

The later poems begin to look back at a long life. ‘Who’s Joking with the Photographer?’ (from A Report from the Border, 2003), describes “all the dark half-tones of the sensuous unsayable/ finding a whole woman there, in her one face.” ‘A Lament for the Makers’ (from Stone Milk, 2007), asserts, “I am alive. I’m human/ Get dressed. Make coffee./ Shore a few lines against my ruin.” The last poem ‘85’ points out “Life will be mine as long as my mind is me.” Her generosity towards friends in poems written for them becomes apparent. Although she probes dark places, her poems feel light and precise, they belie their weight. There’s a wry humour in some and self-depreciation.

Reading through this book felt like picking up a conversation with old friends who will always tell you the truth, not necessarily what you want to hear, but with grace and compassion. This volume serves both as an excellent introduction for those inexplicably not familiar with her poetry and a welcome compilation to dip in and return to for those who do know her work. Stevenson was shadowed by brighter stars, but her reward is a considerable body of poetry that questions what it means to be human, to connect and interact.

Feb 14 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Anne Stevenson

Poetry review – COLLECTED POEMS: Emma Lee surveys Anne Stevenson‘s illustrious career as

summed up in a new compilation of her work

This substantial volume of poems by Anne Stevenson (1933-2020) is drawn from collections beginning with Living in America (1965) and going up to Completing the Circle (2020). Stevenson was a contemporary of Plath and, like Plath, was an American who married an Englishman and came to settle in England (in 1962 for Stevenson). This is both as much and as little as they had in common. Stevenson was a quiet poet, writing and publishing accomplished poems without much fanfare. She was generous in workshops and in support of other poets and will always be remembered fondly. Stevenson frequently revised and recycled poems so some poems have been cut from selections of books where they originally appeared in favour of the latest version in the most recent collection. One of the earliest poems is, ‘The Traveller’ (1961),

To the narrator, this is an ordinary scene. There’s a meal not worth describing, autumnal weather and she notes the leaves dropping under the weight of rain until she stands, presumably checks to she’s not left anything behind, and sees her ghosts. We get to meet some of them. There are also reflections on life from someone used to observing, not being centre stage but directing from the wings. ‘The Mother’ (complete, from Reversals, 1970) personifies this,

The children are loved but there’s also a sense of conflict: the mother is self-less, living for her children and making sacrifices for them by putting them first over her own wants and needs. There’s a second conflict where she acknowledges the life she wants for them may not be the life they want. She asks for it to be passed on. Family life dominates Correspondences A Family History in Letters (1974) which takes letters, journal fragments, newspaper excerpts from members of the imagined Chandler Family through six generations from 1829 to 1972. This is a volume that takes readers outside the poet’s life as the poems lay out family frictions and desires achieved or thwarted through connection.

The maintenance of connection and reputation is picked up again in ‘Respectable House’ (from Enough of Green, 1977) which ends

Behind the façade of respectability lies menace, the threats needed to keep family members in line, lest any entertain the idea of washing the family’s dirty linen in public. Stevenson’s poems may be domestic in subject, but all life is here, and she lifts the veneers of respectability and reputation to prod at the darkness beneath.

Art, specifically poetry, is another subject. In ‘Making Poetry’ (from The Fiction-Makers, 1985), she suggests poets

There’s no simple answer, but the poem suggests, it’s “one of those haunted, undefendable, unpoetic/ crosses we have to find.”

The poems from ‘The Other House’ were written around the time Stevenson wrote Bitter Fame, which is outside the scope of this review. ‘The Other House’ includes three poems for Sylvia Plath. In ‘Letter to Sylvia Plath’, Stevenson writes,

I understand that writing a biography can feel as if your subject has taken you over, that you are inhabiting their life. However, the subject didn’t chose the biographer or to have to have the biography written so it seems an odd image that Plath was perched on the biographer’s shoulder, particularly in light of Stevenson talking about writing Bitter Fame as if Olwyn Hughes was looking over her shoulder. This was the biography that Hughes wanted to “set the record straight” and was the only one she was prepared to authorise. The poem ends,

It seems the biographer was in awe of her subject’s skills but not empathetic to her as a person.

The later poems begin to look back at a long life. ‘Who’s Joking with the Photographer?’ (from A Report from the Border, 2003), describes “all the dark half-tones of the sensuous unsayable/ finding a whole woman there, in her one face.” ‘A Lament for the Makers’ (from Stone Milk, 2007), asserts, “I am alive. I’m human/ Get dressed. Make coffee./ Shore a few lines against my ruin.” The last poem ‘85’ points out “Life will be mine as long as my mind is me.” Her generosity towards friends in poems written for them becomes apparent. Although she probes dark places, her poems feel light and precise, they belie their weight. There’s a wry humour in some and self-depreciation.

Reading through this book felt like picking up a conversation with old friends who will always tell you the truth, not necessarily what you want to hear, but with grace and compassion. This volume serves both as an excellent introduction for those inexplicably not familiar with her poetry and a welcome compilation to dip in and return to for those who do know her work. Stevenson was shadowed by brighter stars, but her reward is a considerable body of poetry that questions what it means to be human, to connect and interact.