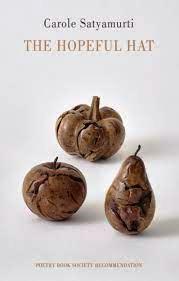

Poetry review – THE HOPEFUL HAT: Stuart Henson reviews Carole Satyamurti’s final collection and finds it both poignant and upbeat

The Hopeful Hat

Carole Satyamurti

Bloodaxe Books

ISBN 978-1-78037-653-0

64pp £10.99

The Hopeful Hat

Carole Satyamurti

Bloodaxe Books

ISBN 978-1-78037-653-0

64pp £10.99

This is Carole Satyamurti’s last book—a collection she was preparing at the time of her death in August 2019—and a powerful testament to her refusal to be diminished by the laryngeal cancer that cruelly took away her physical voice. And though shaded by mortality, it’s not a sad book, rather the reverse, offering as it does its own very personal witness to the courage of the human spirit—a spirit encapsulated by the busker’s ‘hopeful hat’ in the title poem.

Although she never indicated the MS was complete, Carole Satymurti had organised the poems into four sections, grouping them to form a shaped whole, and the first of these, perhaps inevitably, involves a good deal of reflection on the ephemerality of the physical world. ‘Wednesday’, as she observes mordantly at the end of “Obituary”, ‘is collection day.’ Of course it’s just the recycling, but there’s an irony in the line’s positioning, separated at the close of the poem, that gives it an eschatological resonance. The unexpected discovery of the obituary of a lover from fifty years ago sparks a typically wry reflection on the things we keep for reasons we can’t quite understand—in this case a setting of a Baudelaire she was intending to send back with a note on his birthday.

What does one do with past selves –

lock them in; embroider them; forget them;

draw lessons? Or acknowledge them,

like books that formed one once

but won’t be read again.

The poem has become the acknowledgement, but there’s so much more that can’t be preserved: ‘All my things – what a waste / if they should be scattered unloved …’ It’s a conundrum that Satyamurti solves selflessly in “Inheritance” and with wicked humour in ‘ “Wednesday Again”.

Surely it can’t be a week

since last Wednesday.

Is it repeating itself? Am I?

Collections are becoming

more frequent. Soon

it will be Wednesday

twice a week …

She’s determined to keep the tone light, but she’s well aware of the inevitability built into the metaphor:

I know – in the end

Wednesdays will be arriving

ever faster, bonnet to bumper

until they overtake me,

revving, speeding onward,

leaving me behind for good.

And whilst, as an image, it might lack the gravitas of Larkin’s ‘only one ship is seeking us’ it packs a similar kind of punch. Nor is she a journeyman philosopher: a poem like “New York”, from the same section, evokes the excitement of going incognito in a different city, the joy of impermanence, of pretending to be a resident, and then it opens out to assert

This precise mixture of strange and familiar is how I’d live

always, if I could start over in another life. Sometimes

it’s unbearable that there’s only one for each of us

and that the carpet rolls up so very briskly behind us …

That apprehension of the briefness of life carries through into the second section which deals specifically with voice, speech and its loss. The fireworks—glorious but all too momentary—viewed from the fourteenth floor of University College Hospital in “New Year on T14” carry the same metaphorical burden, but this time there’s an added element. Seen from behind the glass on the ward they are strangely mute. And whilst the patients are drawn together in their shared enjoyment of the spectacle we’re hurried on to “Glossal” to confront the more enduring effects of the author’s surgery. Once again, the personal is amplified to make something universal.

A drunkard or a prisoner would be glad

to utter words as compromised as these.

What prudent torture it was,

to cut out dissident tongues,

knowing that the subtlest manoeuvres

of this most potent sixty grams of flesh –

this truth-teller, this incendiary organ,

this evolutionary achievement

as vital to the human core of us

as the heart is – can shift the world.

Remarkably, she is able to resolve the pain and the loss her treatment involves into two further powerful images in the poems that follow.

‘Like a necklace of wasps’,

I tell the doctor. It’s obvious

she doesn’t know what I mean.

Sometimes I feel their soft feet

brushing my clavicle. Exploring

the limits of their territory.

There’s something both sinister and precise about the verbs, and the use of that adjective. ‘soft’, and the associations a word like ‘necklace’ might have with beauty. That’s language skating at the perilous edges of experience. And she goes further in the second section of “Sea Change” – to offer us a metaphor that, in the context, is almost overwhelming:

…if I drew up a list of losses

I’d add the sea.

I was amphibious once,

the sea my other natural element,

shouting as waves curled above me,

driving through, not knowing

when I’d breathe again.

Now, my neck pierced like an organ pipe,

the sea would pour in as an anthem

from the beginning of the world –

a roar, reclaiming me.

Yet The Hopeful Hat isn’t by any means preoccupied with the author’s personal suffering. Section III opens out to address the plight of rough sleepers, sea-borne migrants, the war-torn… indeed the planet itself in “The Climate Game”. Satyamurti is not afraid to call out ‘bluster’, ‘fakery’, ‘manipulation’ and ‘duplicity’ in public life, though in some ways this is the least successful part of the book. Perhaps, if she’d had further time for revision, Carole Satuyamurti wouldn’t have included “War Rhyme”, which deals, as other poems have done, with the drowning of the migrant child that shocked the world in 2015:

He could have been mine,

he could have been yours.

It’s our politicians

who bar the doors…

Genuine sympathy and justified anger are not always sufficient to carry a work of art, and Satyamurti herself is well aware of the difficulty when she asks, at the end of “Small Change”, ‘What has a poem got to do with this?’ Nevertheless, the activist in the poet can’t be suppressed; the obligation to speak out is paramount.

Don’t be afraid to make a poem

raw as sandpaper. And even though

a million protests, twice as many feet,

couldn’t stop a war, get out there

with your small voice, your light tread.

The final movement of the collection is a return to the preoccupations of the opening, and her knack of finding the mot-juste hasn’t deserted her. Remembering her non-sporty schooldays, she conjures a vision of half-time oranges ‘jewel-rare, the lovely colour singing / through the fog-gloom of the muddy pitch.’ and that post-war treat (from which her schemes to avoid games have excluded her) leads on to a memory of grapes on her father’s garden vine: ‘clustered with plump fruit, tight purple skins / slipping off like porn-stars’ underwear.’ As well as the sensuousness of poems like “Succulent”, Satyamurti is capable of a delicate spiritual awareness.

I have weather

to walk in, a life’s

riches laid down

like slow-formed peat.

To be alone

is to taste existence,

its small choices

brushing me like moths …

The last great paradox, and one that Satyamurti doesn’t flinch from facing, is how, when life, with all its vicissitudes, is still so abundant, can we contemplate the end of it?

Feb 18 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Carole Satyamurti

Poetry review – THE HOPEFUL HAT: Stuart Henson reviews Carole Satyamurti’s final collection and finds it both poignant and upbeat

This is Carole Satyamurti’s last book—a collection she was preparing at the time of her death in August 2019—and a powerful testament to her refusal to be diminished by the laryngeal cancer that cruelly took away her physical voice. And though shaded by mortality, it’s not a sad book, rather the reverse, offering as it does its own very personal witness to the courage of the human spirit—a spirit encapsulated by the busker’s ‘hopeful hat’ in the title poem.

Although she never indicated the MS was complete, Carole Satymurti had organised the poems into four sections, grouping them to form a shaped whole, and the first of these, perhaps inevitably, involves a good deal of reflection on the ephemerality of the physical world. ‘Wednesday’, as she observes mordantly at the end of “Obituary”, ‘is collection day.’ Of course it’s just the recycling, but there’s an irony in the line’s positioning, separated at the close of the poem, that gives it an eschatological resonance. The unexpected discovery of the obituary of a lover from fifty years ago sparks a typically wry reflection on the things we keep for reasons we can’t quite understand—in this case a setting of a Baudelaire she was intending to send back with a note on his birthday.

The poem has become the acknowledgement, but there’s so much more that can’t be preserved: ‘All my things – what a waste / if they should be scattered unloved …’ It’s a conundrum that Satyamurti solves selflessly in “Inheritance” and with wicked humour in ‘ “Wednesday Again”.

She’s determined to keep the tone light, but she’s well aware of the inevitability built into the metaphor:

And whilst, as an image, it might lack the gravitas of Larkin’s ‘only one ship is seeking us’ it packs a similar kind of punch. Nor is she a journeyman philosopher: a poem like “New York”, from the same section, evokes the excitement of going incognito in a different city, the joy of impermanence, of pretending to be a resident, and then it opens out to assert

That apprehension of the briefness of life carries through into the second section which deals specifically with voice, speech and its loss. The fireworks—glorious but all too momentary—viewed from the fourteenth floor of University College Hospital in “New Year on T14” carry the same metaphorical burden, but this time there’s an added element. Seen from behind the glass on the ward they are strangely mute. And whilst the patients are drawn together in their shared enjoyment of the spectacle we’re hurried on to “Glossal” to confront the more enduring effects of the author’s surgery. Once again, the personal is amplified to make something universal.

Remarkably, she is able to resolve the pain and the loss her treatment involves into two further powerful images in the poems that follow.

There’s something both sinister and precise about the verbs, and the use of that adjective. ‘soft’, and the associations a word like ‘necklace’ might have with beauty. That’s language skating at the perilous edges of experience. And she goes further in the second section of “Sea Change” – to offer us a metaphor that, in the context, is almost overwhelming:

Yet The Hopeful Hat isn’t by any means preoccupied with the author’s personal suffering. Section III opens out to address the plight of rough sleepers, sea-borne migrants, the war-torn… indeed the planet itself in “The Climate Game”. Satyamurti is not afraid to call out ‘bluster’, ‘fakery’, ‘manipulation’ and ‘duplicity’ in public life, though in some ways this is the least successful part of the book. Perhaps, if she’d had further time for revision, Carole Satuyamurti wouldn’t have included “War Rhyme”, which deals, as other poems have done, with the drowning of the migrant child that shocked the world in 2015:

Genuine sympathy and justified anger are not always sufficient to carry a work of art, and Satyamurti herself is well aware of the difficulty when she asks, at the end of “Small Change”, ‘What has a poem got to do with this?’ Nevertheless, the activist in the poet can’t be suppressed; the obligation to speak out is paramount.

The final movement of the collection is a return to the preoccupations of the opening, and her knack of finding the mot-juste hasn’t deserted her. Remembering her non-sporty schooldays, she conjures a vision of half-time oranges ‘jewel-rare, the lovely colour singing / through the fog-gloom of the muddy pitch.’ and that post-war treat (from which her schemes to avoid games have excluded her) leads on to a memory of grapes on her father’s garden vine: ‘clustered with plump fruit, tight purple skins / slipping off like porn-stars’ underwear.’ As well as the sensuousness of poems like “Succulent”, Satyamurti is capable of a delicate spiritual awareness.

The last great paradox, and one that Satyamurti doesn’t flinch from facing, is how, when life, with all its vicissitudes, is still so abundant, can we contemplate the end of it?