Poetry review – TALKING ME OFF THE ROOF : Charles Rammelkamp is moved by the tenderness of Laurie Kuntz’s poems of love for family and neighbours

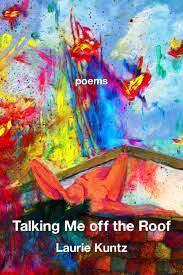

Talking Me off the Roof

Laurie Kuntz

Kelsay Books, 2022

ISBN: 978-1639802166

64 pp $17.00

Talking Me off the Roof

Laurie Kuntz

Kelsay Books, 2022

ISBN: 978-1639802166

64 pp $17.00

A collection of love songs to her husband, Steven, and their son, Noah, Talking Me off the Roof is saturated with an awareness of the brevity of life and the urgency to savor the time we have, with humility and gratitude. Conscious of life’s preciousness, Laurie Kuntz also writes with passion about social issues and the attitude necessary to confront the world’s injustices, while acknowledging and lamenting our frailties as human beings. She does this, moreover, with graciousness and in supple, vivid language.

The book’s title comes from a poem addressed to Steven called “The Way You Talk Me off the Roof,” in which she remembers her husband learning to pick a song out on his guitar called “If We Were Vampires,” whose sad refrain alludes to one of the couple dying before the other and then facing the task of living alone. They reflect with appreciation on their long life together. The poem ends:

These days all we want is not to spend

time alone, to avoid the inevitable,

to be vampires living under many waxing moons.

So many of the poems in Talking Me off the Roof, from “If We Want to Dwell in the Grace of Love, We Must Tempt It to Leave” and “Infinite Tenderness” to “For Better or Worse” and “Goodbye/Hello,” as well as a couple of wedding anniversary poems, express a heartfelt devotion to her spouse, in the awareness of the inevitable finitude of relationships, which only enhances her appreciation for what she has. Kuntz’s poem, “Without,” in which she refers to Donald Hall’s poems to his wife after her leukemia death, is a recognition of this inevitability and an appreciation for the little details that go unnoticed, “until noticing brings an ache that rips / into the marrow of memory.” But, amusingly, when she feels compelled to bring this to Steven’s attention, she encounters him in the kitchen, where he curses her for leaving a bag of frozen vegetables out on the counter, and the moment of tenderness passes! But of course this only underscores the truth of her feeling.

The same appreciation for their son, Noah, recurs in several poems, from “Where to Put the Crayons” and “Milk Teeth” to “Father and Son with Shovel” and “The Trouble with Happiness.” The trouble with happiness is its fleeting nature. Even at the age of six, Noah knows the moment of happiness the family is enjoying on a family vacation in Hawaii is doomed to pass. “I’m just so happy,” he whispers, crying.

You knew then,

on one of those days,

these infinite moments of our lives

held in the pockets of your tears,

would never last.

The awareness of the evanescence at the heart of our experience is on display again and again, in poems like “Metastasis,” in which the everyday contentment that we so often take for granted is jarred when a cancer diagnosis is received.

How could anyone bemoan the tedious –

hanging clothes in an autumn sun

or beating rugs of lint and hair,

the daily chores done with ease are a miracle.

“To Do: When on Quarantine,” “Amazing and Annoying” “The Person Right Next to You” and “That’s What You Say” – the last one being a poem about her mother’s death in a nursing home – are other poems that highlight the transience and fragility of existence.

Kuntz’s attitude admirably spills over into larger, social causes, in praise of the activists among us. “Darnella’s Duty” is an ode to the young woman who recorded George Floyd’s murder on her cellphone, taking on the burden of bearing witness to “a purpose too cruel” for her young age. “Sons Have Sleepovers While Putin Deploys Troops” acknowledges the cruel shenanigans of the Russian dictator. “Why I Don’t Write About Florida’s Don’t Say Gay Bill” – after the poet Toi Derricotte – spells out her horror at the heartless law initiated by Ron DeSantis. Kuntz lives in Florida.

Because it is more stifling than the daily temperature.

Because rhymes are meant for poetry not repression.

Because the phrase, like sour milk, puckers my tongue.

Because the correct pronoun hardly matters

when it silences everyone.

But it’s Kuntz’s celebration of the quotidian, the value she places on noticing and an accompanying attitude of gratitude, that ultimately anchors this splendid collection. “Asunción” is a poem in which she fears memory loss and the way it seems to negate experience, particularly as it relates to her marriage. “Details which belonged to us / slip off memory’s hanger like a silk shirt,” she writes, mourning the forfeiture of details “lost in the tattered purse of recollection.” In the final poem, “Directions to Come Ashore,” reflecting on the challenges of isolation (think: quarantine), Kuntz sums it all up:

In these times we need the ordinary,

the quotidian moments

This, finally, is how we talk ourselves off the window ledge, lower the blood pressure. As she asks in “Grappling with Gratitude”: “Where is the marrow of gratitude?” It’s in the admiration of the everyday, fleeting though this may be. Kuntz dedicates Talking Me off the Roof “For Steven and Noah: On level ground,” back on earth and full of appreciation for what she has.

Jan 16 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Laurie Kuntz

Poetry review – TALKING ME OFF THE ROOF : Charles Rammelkamp is moved by the tenderness of Laurie Kuntz’s poems of love for family and neighbours

A collection of love songs to her husband, Steven, and their son, Noah, Talking Me off the Roof is saturated with an awareness of the brevity of life and the urgency to savor the time we have, with humility and gratitude. Conscious of life’s preciousness, Laurie Kuntz also writes with passion about social issues and the attitude necessary to confront the world’s injustices, while acknowledging and lamenting our frailties as human beings. She does this, moreover, with graciousness and in supple, vivid language.

The book’s title comes from a poem addressed to Steven called “The Way You Talk Me off the Roof,” in which she remembers her husband learning to pick a song out on his guitar called “If We Were Vampires,” whose sad refrain alludes to one of the couple dying before the other and then facing the task of living alone. They reflect with appreciation on their long life together. The poem ends:

These days all we want is not to spend time alone, to avoid the inevitable, to be vampires living under many waxing moons.So many of the poems in Talking Me off the Roof, from “If We Want to Dwell in the Grace of Love, We Must Tempt It to Leave” and “Infinite Tenderness” to “For Better or Worse” and “Goodbye/Hello,” as well as a couple of wedding anniversary poems, express a heartfelt devotion to her spouse, in the awareness of the inevitable finitude of relationships, which only enhances her appreciation for what she has. Kuntz’s poem, “Without,” in which she refers to Donald Hall’s poems to his wife after her leukemia death, is a recognition of this inevitability and an appreciation for the little details that go unnoticed, “until noticing brings an ache that rips / into the marrow of memory.” But, amusingly, when she feels compelled to bring this to Steven’s attention, she encounters him in the kitchen, where he curses her for leaving a bag of frozen vegetables out on the counter, and the moment of tenderness passes! But of course this only underscores the truth of her feeling.

The same appreciation for their son, Noah, recurs in several poems, from “Where to Put the Crayons” and “Milk Teeth” to “Father and Son with Shovel” and “The Trouble with Happiness.” The trouble with happiness is its fleeting nature. Even at the age of six, Noah knows the moment of happiness the family is enjoying on a family vacation in Hawaii is doomed to pass. “I’m just so happy,” he whispers, crying.

You knew then, on one of those days, these infinite moments of our lives held in the pockets of your tears, would never last.The awareness of the evanescence at the heart of our experience is on display again and again, in poems like “Metastasis,” in which the everyday contentment that we so often take for granted is jarred when a cancer diagnosis is received.

“To Do: When on Quarantine,” “Amazing and Annoying” “The Person Right Next to You” and “That’s What You Say” – the last one being a poem about her mother’s death in a nursing home – are other poems that highlight the transience and fragility of existence.

Kuntz’s attitude admirably spills over into larger, social causes, in praise of the activists among us. “Darnella’s Duty” is an ode to the young woman who recorded George Floyd’s murder on her cellphone, taking on the burden of bearing witness to “a purpose too cruel” for her young age. “Sons Have Sleepovers While Putin Deploys Troops” acknowledges the cruel shenanigans of the Russian dictator. “Why I Don’t Write About Florida’s Don’t Say Gay Bill” – after the poet Toi Derricotte – spells out her horror at the heartless law initiated by Ron DeSantis. Kuntz lives in Florida.

But it’s Kuntz’s celebration of the quotidian, the value she places on noticing and an accompanying attitude of gratitude, that ultimately anchors this splendid collection. “Asunción” is a poem in which she fears memory loss and the way it seems to negate experience, particularly as it relates to her marriage. “Details which belonged to us / slip off memory’s hanger like a silk shirt,” she writes, mourning the forfeiture of details “lost in the tattered purse of recollection.” In the final poem, “Directions to Come Ashore,” reflecting on the challenges of isolation (think: quarantine), Kuntz sums it all up:

This, finally, is how we talk ourselves off the window ledge, lower the blood pressure. As she asks in “Grappling with Gratitude”: “Where is the marrow of gratitude?” It’s in the admiration of the everyday, fleeting though this may be. Kuntz dedicates Talking Me off the Roof “For Steven and Noah: On level ground,” back on earth and full of appreciation for what she has.