Poetry review – LARDER: DA Prince admires the way that Rhona McAdam’s poetry cheerfully celebrates the fruits of nature while seriously urging us to care for the natural world

Larder

Rhona McAdam

Caitlin Press, 2022

ISBN 978-1-773860831

$16 (US); $20 (CAD)

Larder

Rhona McAdam

Caitlin Press, 2022

ISBN 978-1-773860831

$16 (US); $20 (CAD)

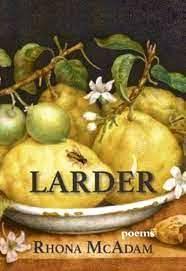

Larder has a cover which is not only beautiful in its self but is also —unusually — a good indicator of what to expect from the poems. Look hard: at the details of the fruit, the reality and individuality of those knobbly lemons; the way young and mature lemons occur side by side; how the seasons are suggested (lemons bear blossom and fruit on the tree simultaneously); the gentleness of that wasp; the everyday honest plainness of the glazed earthenware bowl, chipped with use. It’s about detail and texture and intimate sensory kinship, about rendering the subject as perfectly as possible, about arousing the viewer’s senses. I know what those lemons would smell like; they’d have grown in the garden near where they were painted.

Rhona McAdam’s poems share the characteristics of Giovanna Garzoni’s (painted in Italy in the mid-seventeenth century). McAdam is an ecologist and nutritionist with a poet’s eye for detail, for the inter-connections within the natural world, with a relish for words and how to place them in ways that create fresh associations. These can be both visual and auditory; she listens to her poems and the music within them.

The opening poem, ‘Anna’s Hummingbird’ with its repeated ‘-um’ shows she can create the urgent excitement of spring —

When the hummingbird plummets,

a whistling blur through the plum blossom,

it will be spring.

Two aurally-rich lines, plus the movement of the ‘whistling blur’, are complemented by the promise in the monosyllables of ‘it will be spring.’ This balance between richness and simple directness in language is one of the ways McAdam explores connections with the natural world; in her poetry it is shown as both a place of sensuous delight and a space of elemental simplicity. In ‘Tent Caterpillars’ she describes these ‘black worms, numerous/ and immaterial’ letting her play with vowels evoke this tangled mass; she shares her enjoyment of how they grow ‘into their skin/ and gilding bristle,/ until, lions at last/ they bask on tree limbs’ until—

We swear we hear them

whiskering up the walls,

their thousand fingers

caressing our roofs

How well ‘whiskering’ plays with sound and texture. She pays attention to spiders, wasps, wild bees, wireworms — tiny insects that play a part in the connectedness of nature. In ‘Wild Bees’ she shows the busyness of the bees by way of repetitions: ‘A day’s work/ and a day’s work and a day and a day’. It’s effective, using words as small as the bees themselves: ‘We fly, we crawl, we gather./ And again.’

The collection is grouped into four sections, not labelled but instead introduced by an epigraph; it’s a way of engaging the reader in what will follow. The sections are, very roughly, about the land being an organism; eating; human connection to the earth; the body’s intuitive intelligence. Larder is an all-encompassing title. All of these could, of course, have been covered in prose; McAdam is the author of Digging the City, a manifesto for urban agriculture and her life’s work is a commitment to raising the quality of food production in every aspect. In these poems, however, she can take the reader inside her enthusiasms and poetry is the perfect medium. I’m concentrating on how she does this and where her imagination comes in.

It might be with light-touch humour, as in ‘Roasting Vegetables’ —

We’d like to believe

they’d rolled in from the garden,

processions of plenty,

innocent and clean, shrugging off

their origins in dirt, black residue of growing things

— where the earthy vegetables bear little resemblance to the scrubbed, cleansed and packaged supermarket offerings. Or in ‘Caramelized Garlic & Squash Tart’, where she tests out long lines (as well as the recipe) to great effect, starting with the difficulty of cooking in an unfamiliar kitchen —

Blind baking in another strange kitchen

I miss so much what is stashed so far away

in the farthest reaches of my cupboards: those baking beads,

shiny pearls of heavy clay, hauled from England,

snug and greasy in their plastic tub.

It’s easy to overlook how the repetition of ‘so’ in l.2 emphasises the distance, or how the apparently unappetising ‘snug and greasy’ is changed into something longed-for. It’s an appetite-stirring recipe — and you could cook it from this poem — but it’s more than that: it catches the ‘fretting’ of the struggle, the sense of place and time through the evocation of ‘cheese as white and soft as the snow beyond the window.’ It’s about the whole experience of creating one unified dish out of separate ingredients.

This is how McAdam brings a cook’s practical knowledge into her poems; she knows about textures and ripening and how the outside world of weather and season ends up on the kitchen table. ‘Fruit Cake’ has all the ingredients, recognised for what they have become: ‘the buckshot of currants/ have lost the desire for round’ and ‘Cherries, gone glassy with sugar,/ forget they were ever fruit.’ Given the time they need these fruits are transformed —

all drenched in brandy and left

to remember the shapes

their skins abandoned

all those summer days ago,

drinking the liquor until the bowl

exudes lost grapes.

Despite its wonder and celebration of what the natural world gives, Larder isn’t all idyll: the poems move towards an acceptance of the pressures of living in the present day, and of mortality. ‘Home is a Different Country’, taking its epigraph from John Burnside, remembers how the Covid pandemic has changed society and our responses —

The house has never been cleaner

the streets quieter

the buses more empty

churning the night, every light on,

every seat free

but one.

Framed in simple language, this is unsentimental realism. In the first months of the pandemic we lived differently: in some ways we still do. I line up with ‘Our hands have never been cleaner/ our larders more curiously stocked’ although only in Canada (McAdam’s home) do ‘Wolves and cougars/ take a few liberties/ in our empty streets.’ All the UK can offer in return are film-clips of the less-harmful Kashmiri goats roaming the streets and gardens of Llandudno (and the brief pleasure they gave us). Shopping became ‘sluggish hopscotch’ negotiating the markings on the floor. McAdam doesn’t need to name Covid.

Its shadow falls across ‘Every Night I Catch My Breath’ where her breath ‘whispers that I am alive’ while also stilling ‘the staccato of my heart.’ The poems in the final section tilt towards frailty, the vulnerability of the body, death, and ways of managing inevitable fears. The language of shadows and darkness threads through these poems but never dominates; a good balance of the personal and the universal in a way that poetry handles best.

It’s a well-worn trope that poems are like icebergs, seven-tenths under the surface, but that doesn’t remove anything from its truth. What underlies this collection is an urgent political argument, with care for every aspect of the earth and its connected structures. While tastes and textures touch our senses in individual poems, the foundation of the collection comes from recognising the value of everything in nature: yes, even the tick. Rhona McAdam has, her biography tells us, already published ten poetry collections. Experience, along with the breadth of her concern for living things, makes her poetry feel both confident in technique and fresh. This is both a collection to savour and an environmental cause to embrace.

Dec 11 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Rhona McAdam

Poetry review – LARDER: DA Prince admires the way that Rhona McAdam’s poetry cheerfully celebrates the fruits of nature while seriously urging us to care for the natural world

Larder has a cover which is not only beautiful in its self but is also —unusually — a good indicator of what to expect from the poems. Look hard: at the details of the fruit, the reality and individuality of those knobbly lemons; the way young and mature lemons occur side by side; how the seasons are suggested (lemons bear blossom and fruit on the tree simultaneously); the gentleness of that wasp; the everyday honest plainness of the glazed earthenware bowl, chipped with use. It’s about detail and texture and intimate sensory kinship, about rendering the subject as perfectly as possible, about arousing the viewer’s senses. I know what those lemons would smell like; they’d have grown in the garden near where they were painted.

Rhona McAdam’s poems share the characteristics of Giovanna Garzoni’s (painted in Italy in the mid-seventeenth century). McAdam is an ecologist and nutritionist with a poet’s eye for detail, for the inter-connections within the natural world, with a relish for words and how to place them in ways that create fresh associations. These can be both visual and auditory; she listens to her poems and the music within them.

The opening poem, ‘Anna’s Hummingbird’ with its repeated ‘-um’ shows she can create the urgent excitement of spring —

Two aurally-rich lines, plus the movement of the ‘whistling blur’, are complemented by the promise in the monosyllables of ‘it will be spring.’ This balance between richness and simple directness in language is one of the ways McAdam explores connections with the natural world; in her poetry it is shown as both a place of sensuous delight and a space of elemental simplicity. In ‘Tent Caterpillars’ she describes these ‘black worms, numerous/ and immaterial’ letting her play with vowels evoke this tangled mass; she shares her enjoyment of how they grow ‘into their skin/ and gilding bristle,/ until, lions at last/ they bask on tree limbs’ until—

How well ‘whiskering’ plays with sound and texture. She pays attention to spiders, wasps, wild bees, wireworms — tiny insects that play a part in the connectedness of nature. In ‘Wild Bees’ she shows the busyness of the bees by way of repetitions: ‘A day’s work/ and a day’s work and a day and a day’. It’s effective, using words as small as the bees themselves: ‘We fly, we crawl, we gather./ And again.’

The collection is grouped into four sections, not labelled but instead introduced by an epigraph; it’s a way of engaging the reader in what will follow. The sections are, very roughly, about the land being an organism; eating; human connection to the earth; the body’s intuitive intelligence. Larder is an all-encompassing title. All of these could, of course, have been covered in prose; McAdam is the author of Digging the City, a manifesto for urban agriculture and her life’s work is a commitment to raising the quality of food production in every aspect. In these poems, however, she can take the reader inside her enthusiasms and poetry is the perfect medium. I’m concentrating on how she does this and where her imagination comes in.

It might be with light-touch humour, as in ‘Roasting Vegetables’ —

— where the earthy vegetables bear little resemblance to the scrubbed, cleansed and packaged supermarket offerings. Or in ‘Caramelized Garlic & Squash Tart’, where she tests out long lines (as well as the recipe) to great effect, starting with the difficulty of cooking in an unfamiliar kitchen —

It’s easy to overlook how the repetition of ‘so’ in l.2 emphasises the distance, or how the apparently unappetising ‘snug and greasy’ is changed into something longed-for. It’s an appetite-stirring recipe — and you could cook it from this poem — but it’s more than that: it catches the ‘fretting’ of the struggle, the sense of place and time through the evocation of ‘cheese as white and soft as the snow beyond the window.’ It’s about the whole experience of creating one unified dish out of separate ingredients.

This is how McAdam brings a cook’s practical knowledge into her poems; she knows about textures and ripening and how the outside world of weather and season ends up on the kitchen table. ‘Fruit Cake’ has all the ingredients, recognised for what they have become: ‘the buckshot of currants/ have lost the desire for round’ and ‘Cherries, gone glassy with sugar,/ forget they were ever fruit.’ Given the time they need these fruits are transformed —

Despite its wonder and celebration of what the natural world gives, Larder isn’t all idyll: the poems move towards an acceptance of the pressures of living in the present day, and of mortality. ‘Home is a Different Country’, taking its epigraph from John Burnside, remembers how the Covid pandemic has changed society and our responses —

Framed in simple language, this is unsentimental realism. In the first months of the pandemic we lived differently: in some ways we still do. I line up with ‘Our hands have never been cleaner/ our larders more curiously stocked’ although only in Canada (McAdam’s home) do ‘Wolves and cougars/ take a few liberties/ in our empty streets.’ All the UK can offer in return are film-clips of the less-harmful Kashmiri goats roaming the streets and gardens of Llandudno (and the brief pleasure they gave us). Shopping became ‘sluggish hopscotch’ negotiating the markings on the floor. McAdam doesn’t need to name Covid.

Its shadow falls across ‘Every Night I Catch My Breath’ where her breath ‘whispers that I am alive’ while also stilling ‘the staccato of my heart.’ The poems in the final section tilt towards frailty, the vulnerability of the body, death, and ways of managing inevitable fears. The language of shadows and darkness threads through these poems but never dominates; a good balance of the personal and the universal in a way that poetry handles best.

It’s a well-worn trope that poems are like icebergs, seven-tenths under the surface, but that doesn’t remove anything from its truth. What underlies this collection is an urgent political argument, with care for every aspect of the earth and its connected structures. While tastes and textures touch our senses in individual poems, the foundation of the collection comes from recognising the value of everything in nature: yes, even the tick. Rhona McAdam has, her biography tells us, already published ten poetry collections. Experience, along with the breadth of her concern for living things, makes her poetry feel both confident in technique and fresh. This is both a collection to savour and an environmental cause to embrace.