Poetry review – OLD FRIENDS: Alex Josephy is drawn in by Hannah Lowe’s creative approach to personal and social history

Old Friends

Hannah Lowe

Hercules Editions, 2022.

ISBN:978-1-9161971-9-0

£10

Old Friends

Hannah Lowe

Hercules Editions, 2022.

ISBN:978-1-9161971-9-0

£10

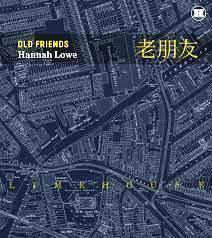

In this exquisite limited edition, Hannah Lowe’s poems and selected photos, movie posters and other illustrations speak back and forth across small square pages, drawing the reader into real and fictional stories about the historic Chinese community of Limehouse in London’s East End. There is a contextualising introduction by Anna Chen, and the book ends with a dialogue between Lowe and fellow poet Richard Scott. Old Friends is sister to Rock, Bird, Butterfly, in the same limited edition.

After Lowe’s success as winner of the Costa Book of the Year award 2021 with The Kids, and her equally well-received Bloodaxe collections, Chick and Chan, she is now a poet whose voice is instantly recognizable; and – speaking for myself – whose work has continuity and an authenticity that goes on being a surprise and delight to the reader.

Throughout the collection, Lowe explicitly brings to life Derrida’s notion of ‘hauntology’: ‘the haunting persistence of the social or cultural past’, intensely felt through what she knows of the lives of her father and grandfather. In the final poem, she describes a legacy of pain and cruelty that persists after colonial oppression, but also a gift of hope and skill:

He tied my father to the bed with rope.

The rope dissolved. He taught him how to cook.

A telling image in the same poem pays tribute to the inspiration she has found in this focus on family and place: ‘My grandfather is captain of this book’.

The book contains thirteen numbered poems. They are consistent in form, each poem composed of two or more seven line stanzas, so that some coalesce into sonnets or near-sonnets. Lowe’s delicate rhymes, half-rhymes and other musical qualities give the poems a pleasing fluidity, and quietly convey a sense of affection, even when the poems deal with past trauma.

(On closely re-reading, I did notice a few typos; these did not really diminish my enjoyment of the poems (it’s happened to me too!), but perhaps a second edition could set them right.)

The ‘Old Friends’ was a Chinese restaurant in Mandarin Street near the former London docks, no longer to be found there. Or was it known as ‘Good Friends’, or ‘New Friends’? Or were those in fact other restaurants, in other corners of the East End? (I myself had these same uncertainties when I moved to the East End – marginalised areas of history have a tendency to evaporate). As Lowe explores Limehouse and researches stories of the Chinese seamen and their families who settled there during and after the Napoleonic wars, she is also delving into intricacies of memory, further intersected by the propagation of myths around an immigrant community.

I loved the interaction between the words of the poems and the images on facing pages, for instance in the first, untitled poem where in the restaurant, everything is hazy:

Ghost-waiters in bow ties swim around the edges,

dispersible as the images in dreams

And yet the struggle is worthwhile; eventually Lowe achieves a moment of clarity that perhaps explains and justifies her quest:

Only my bowl of won ton soup is clear,

pulled into focus through my mind’s binoculars.

The 1950 photo on the opposite page shows the ‘Old Friends’ doorway, in which stand two chefs with folded arms and creased faces, not exactly welcoming us in, but asserting their presence.

Other poems focus on the poet’s quest to connect more fully with her Chinese roots, often through cooking:

as though the acts of making, steaming, eating

from authentic Chinese bowls, will bring

me closer to the China somewhere inside

of me.

She learns that won ton ‘loosely means cloud-swallow’ , and the ‘splosh of soup’:

…brings back my father,

and lets me hear the lapping of the river

hauling in its cargo.

Although she is rightly wary of the temptation to romanticise or exoticise the old East End and Chinese ways, there is infectious excitement in her discovery of documents and photos that bring her closer to understanding the past. ‘The photographs are monochrome’, but ‘I see colour… I paint in red, gold, green’. In light strokes, she conveys the sense of finding and revelling in another world, as in early film:

the way that Thullier, in her Paris studio

had two hundred women on an assembly line

to colour films, like Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon.

Other poems, though, explore the pervasive negative portrayal of Chinese people and culture in Western media, for instance ’Brilliant Chang’ who in the 1920s, ‘hypnotised…white girls’, and ’sallow, evil-angled’ Fu Manchu. As Lowe points out, such stories were eagerly seized on and made lurid by writers whose only contact with Chinese culture was imaginary:

China swelled and swilled in the heads of Rohmer,

Charles Dickens, Oscar Wilde, Thomas Burke …

…What purpose, these imaginings?

Moving toward the present day, Poem 7 illuminates the potentially invasive effect of collecting and publicising oral history. A century ago, East End tours promoted the worst myths about ‘the Yellow Peril’, a music-hall song revelled in racist descriptions of Chinatown, ‘where slitty-eyed Chinks take 40 winks’ (sic):

Ladies and gentlemen, just here,

beyond this door, a real opium den!

And down this street, a murder!

In ‘The Oral Historians’, an old woman known as Limehouse Annie is both exploited (‘they wheel her round the houses’) and disbelieved:

They wonder if those things are in her head.

She might be adding in a scoop of spice

They ask her for her stories more than twice…

The effect is nauseating, but queasily familiar. And Lowe makes a clear link to contemporary sinophobia; in poem 6:

Joanna phones to say she’s heard a rumour –

Covid cooked up in a lab – the plan

of bad Chinese – like Fu Manchu’s poppy poison.

Anna Chan’s helpful introduction outlines two ‘Grand Narratives’ concerning China and its diaspora: ‘one which demonises its subject, and the other which humanises.’ Lowe achieves subtle effects by moving between these views, alert to the hints of humanity to be found even in negative representations.

Lowe has Chinese and Jamaican heritage, yet as she says herself, is ‘ostensibly middle-class, white (-looking)’, and in her poems she often reflects on what she identifies as ‘post-colonial blues’ – ‘What do writers do or make with trauma that is not their own?’ And, equally, what do they do with a complex, mixed-race identity that is not immediately apparent? A poem I found especially moving in this respect depicts her son Rory at school where his class is ‘making paper lanterns/ for Chinese new year’, ’telling everyone he’s Chinese,’ to the disbelief of his teacher. The colour red (special and lucky in China) permeates the poem, from the lanterns like ‘fat red tears’, to Rory’s red hair ‘like a rooster’s comb’ and his name: ‘Rory means Red King.’ I loved the way the poet is present in every poem, striving to do justice to her family history and to look beyond the stereotypes into a fascinating corner of the old East End.

Dec 19 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Hannah Lowe

Poetry review – OLD FRIENDS: Alex Josephy is drawn in by Hannah Lowe’s creative approach to personal and social history

In this exquisite limited edition, Hannah Lowe’s poems and selected photos, movie posters and other illustrations speak back and forth across small square pages, drawing the reader into real and fictional stories about the historic Chinese community of Limehouse in London’s East End. There is a contextualising introduction by Anna Chen, and the book ends with a dialogue between Lowe and fellow poet Richard Scott. Old Friends is sister to Rock, Bird, Butterfly, in the same limited edition.

After Lowe’s success as winner of the Costa Book of the Year award 2021 with The Kids, and her equally well-received Bloodaxe collections, Chick and Chan, she is now a poet whose voice is instantly recognizable; and – speaking for myself – whose work has continuity and an authenticity that goes on being a surprise and delight to the reader.

Throughout the collection, Lowe explicitly brings to life Derrida’s notion of ‘hauntology’: ‘the haunting persistence of the social or cultural past’, intensely felt through what she knows of the lives of her father and grandfather. In the final poem, she describes a legacy of pain and cruelty that persists after colonial oppression, but also a gift of hope and skill:

A telling image in the same poem pays tribute to the inspiration she has found in this focus on family and place: ‘My grandfather is captain of this book’.

The book contains thirteen numbered poems. They are consistent in form, each poem composed of two or more seven line stanzas, so that some coalesce into sonnets or near-sonnets. Lowe’s delicate rhymes, half-rhymes and other musical qualities give the poems a pleasing fluidity, and quietly convey a sense of affection, even when the poems deal with past trauma.

(On closely re-reading, I did notice a few typos; these did not really diminish my enjoyment of the poems (it’s happened to me too!), but perhaps a second edition could set them right.)

The ‘Old Friends’ was a Chinese restaurant in Mandarin Street near the former London docks, no longer to be found there. Or was it known as ‘Good Friends’, or ‘New Friends’? Or were those in fact other restaurants, in other corners of the East End? (I myself had these same uncertainties when I moved to the East End – marginalised areas of history have a tendency to evaporate). As Lowe explores Limehouse and researches stories of the Chinese seamen and their families who settled there during and after the Napoleonic wars, she is also delving into intricacies of memory, further intersected by the propagation of myths around an immigrant community.

I loved the interaction between the words of the poems and the images on facing pages, for instance in the first, untitled poem where in the restaurant, everything is hazy:

And yet the struggle is worthwhile; eventually Lowe achieves a moment of clarity that perhaps explains and justifies her quest:

The 1950 photo on the opposite page shows the ‘Old Friends’ doorway, in which stand two chefs with folded arms and creased faces, not exactly welcoming us in, but asserting their presence.

Other poems focus on the poet’s quest to connect more fully with her Chinese roots, often through cooking:

She learns that won ton ‘loosely means cloud-swallow’ , and the ‘splosh of soup’:

Although she is rightly wary of the temptation to romanticise or exoticise the old East End and Chinese ways, there is infectious excitement in her discovery of documents and photos that bring her closer to understanding the past. ‘The photographs are monochrome’, but ‘I see colour… I paint in red, gold, green’. In light strokes, she conveys the sense of finding and revelling in another world, as in early film:

Other poems, though, explore the pervasive negative portrayal of Chinese people and culture in Western media, for instance ’Brilliant Chang’ who in the 1920s, ‘hypnotised…white girls’, and ’sallow, evil-angled’ Fu Manchu. As Lowe points out, such stories were eagerly seized on and made lurid by writers whose only contact with Chinese culture was imaginary:

Moving toward the present day, Poem 7 illuminates the potentially invasive effect of collecting and publicising oral history. A century ago, East End tours promoted the worst myths about ‘the Yellow Peril’, a music-hall song revelled in racist descriptions of Chinatown, ‘where slitty-eyed Chinks take 40 winks’ (sic):

In ‘The Oral Historians’, an old woman known as Limehouse Annie is both exploited (‘they wheel her round the houses’) and disbelieved:

The effect is nauseating, but queasily familiar. And Lowe makes a clear link to contemporary sinophobia; in poem 6:

Anna Chan’s helpful introduction outlines two ‘Grand Narratives’ concerning China and its diaspora: ‘one which demonises its subject, and the other which humanises.’ Lowe achieves subtle effects by moving between these views, alert to the hints of humanity to be found even in negative representations.

Lowe has Chinese and Jamaican heritage, yet as she says herself, is ‘ostensibly middle-class, white (-looking)’, and in her poems she often reflects on what she identifies as ‘post-colonial blues’ – ‘What do writers do or make with trauma that is not their own?’ And, equally, what do they do with a complex, mixed-race identity that is not immediately apparent? A poem I found especially moving in this respect depicts her son Rory at school where his class is ‘making paper lanterns/ for Chinese new year’, ’telling everyone he’s Chinese,’ to the disbelief of his teacher. The colour red (special and lucky in China) permeates the poem, from the lanterns like ‘fat red tears’, to Rory’s red hair ‘like a rooster’s comb’ and his name: ‘Rory means Red King.’ I loved the way the poet is present in every poem, striving to do justice to her family history and to look beyond the stereotypes into a fascinating corner of the old East End.