Poetry review – FLAMINGO: Emma Storr is greatly impressed by a debut pamphlet from Kathryn Bevis

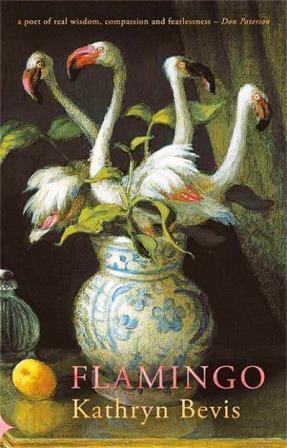

Flamingo

Kathryn Bevis

Seren Books

ISBN: 978-1-78172-693-8

35pp £6.00

Flamingo

Kathryn Bevis

Seren Books

ISBN: 978-1-78172-693-8

35pp £6.00

It’s a delight to review this debut pamphlet by Kathryn Bevis. Flamingo contains 31 poems of extraordinary bravery, variety and skill. Bevis’s wit and inventiveness shine through, even when dealing with painful subjects such as a cancer diagnosis.

The pamphlet opens with the splendid ‘Wonder Woman Questions her Status as a ‘70’s Symbol of Female Empowerment’. The objectification of the female body and intrusive male gaze is cleverly explored in surprising imagery:

my body a shining slice

of cherry cheesecake, my breasts twin spaniels

off the leash, the bouncy castle of my thighs.

After describing the degradation she endures in comparison to Spiderman and Superman, Wonder Woman becomes more vocal in her demands. The poem ends viscerally and defiantly:

Go, apprehend your creeps. I want my sweetbreads

skinned and a big white bed that’s empty save for me.

Bevis often employs the surreal to give us refreshing and new perspectives on serious societal problems. The dark humour in both “Teddy” and “The Smuggler” is chilling and adds to the impact of these poems featuring deeply disturbing male behaviour towards women. “Teddy” has an arresting first line: ‘Delia suspected that her teddy bear was gaslighting her’. In stanza three we learn:

Teddy said none of the other bears was good enough

for Delia, not the best version of her, the version only he

could help her work towards.

Teddy’s comments, italicised throughout the poem, demonstrate his insidious power over Delia. Unlike Wonder Woman, who rebels, Delia seems to accept Teddy’s viewpoint and by the end has been completely brainwashed.

It wasn’t all bad. Teddy taught her the difference between

less and fewer, its and it’s, no and yes. He was good at rules

and there much that Delia still needed to learn.

Humour is also used subtly to highlight the pressure placed on women to have children. In “Matryoshka” the text is arranged on the page to mirror the seven Russian dolls stacked inside each other and diminishing in size. The narrator is smug about their ability to each produce another daughter, a ‘pretty chick’, apart from the smallest doll who ‘was born with no space / inside. That’s right’. We are told that the other six dolls don’t judge her, but there’s an implicit criticism of a female who is unable to have children. On the opposite page to “Matryoshka” is the poem “In which I imagine my aborted foetus sings to me”, a juxtaposition that emphasises the loss experienced when choosing not to become a parent. The foetus sings in lyrical, broken verse:

listen to me i have known paradise

have learned by heart your heartbeat’s song

The poem ends on a powerful metaphor that encapsulates both the umbilical connection between mother and child and also the idea of heritage:

i was your well-wound spool your coil of line

that binds

A different use of textile imagery emerges in the poem “Knitting Nan Nan”. Grandma gradually take shape as the narrator knits her slippers in ‘shabby, worsted wool’ and then moves up Nan Nan’s body:

I knit the screeching polyester dress she wore to clean

the step, knit her freckled hands, her wedding band, knit

the tumour nestling in her breast.

The detailed description of Nan Nan’s legs, trunk and bingo wings before these lines means we have a clear image of her. The gap between stanzas at this point adds to the shock of learning about the breast cancer. Nan Nan then ‘casts herself off’:

Now, she lies in my lap as I once did in hers: her neck’s

soft crepe, that trace of B & H, the shrill acrylic of her voice.

The ‘acrylic’ recalls the ‘screeching’ dress we were introduced to earlier. “Knitting Nan Nan” also demonstrates Bevis’s skill in using the senses of touch, hearing and sight to paint a tender portrait of a much-loved grandmother.

An interesting use of negatives is evident in the poems “Miss means both Mother and No-one” and “In this poem, your routine bloods have come back normal”. In the first of these there is a long list of reasons why the trainee teacher is not crying which builds up the tension for the reader to find out what is really going on. Eventually we are told she is crying for ‘let’s-call-him Jaydon, Ahmed, Tom’ or later ‘let’s-call-her Aisha, Kayla, Kim’ who, in different ways, have all exhibited desperate cries for help. The list of names showing us how many children are being failed by society on a regular basis, adds to the hopelessness of the situation.

Another list of negatives appears in a different context in “In this poem, your bloods have come back normal”. The speaker addresses an unidentified person, (possibly her mother) and imagines an alternative to the reality of cancer. Her constant denial underlines the fear felt both by the cancer sufferer and by the speaker when waiting for test results:

In this poem, there’s no need for us to learn how

tumours are graded and staged post-operatively

or to study your body’s geometry of area and volume,

its algebra of variables and unknowns.

The final stanza ends ominously:

…In this

poem you’re whole. We’re not waiting for what’s next.

Flamingo concludes with a sequence of poems that demonstrate Bevis’s bravery, both in the content matter (a cancer diagnosis) and in the imaginative use of metaphor and imagery. The poetry is very moving without ever being maudlin. We read about the speaker’s appreciation of the natural world and of her partner, Ollie. “This” is a short poem of three stanzas, all of which end with the line ‘Nothing is worth more than this day’. The repetition works well to suggest time is running out and every moment must be savoured. The lyrical descriptions of the landscape, birds, light on water and the breeze sing on the page:

Here, the wind toys with leaves like loose

change in the pockets of the sky.

The poem “My Cancer as a Ring-Tailed Lemur” uses the energy and unpredictability of this animal to characterise the way cancer spreads and the difficulty of ‘catching’ it on different scans – ultrasound, then MRI and finally PET-CT.

She’s up and off alright: a lope,

a leap. She careens through my branches,

omnivorous for bone and liver, brain.

The narrator and the lemur cohabit but the treatment for cancer is destroying their habitat, the body. They are both fighting ‘a forest fire’ that ultimately will destroy them.

The final poem in the pamphlet ‘Flamingo’ is a mix of deep sadness and something verging on the glorious. It starts ‘My love, when I die, I’ll turn flamingo:’ The second stanza reassures:

In this afterworld, some days I’ll fix

one foot in mud, find infinite repose:

the poise of a yogi in prayer.

The assonance of ‘repose’ and ‘poise’ add to the sense of an invocation, a peaceful place.

In the final stanza, the flamingos are enjoying themselves. The afterlife seems an attractive place where ‘the dead all flock / together.’

We meet at the saline lake, dance

our shuffle-legged shimmy, flick our heads

like tango partners.

We are brought back to reality and to the poignant message at the end of the poem:

After the illness,

after the grief, the pain – as you will do,

sweetheart – the dead must learn to love again.

I don’t think I have ever reviewed such a stunning and original pamphlet as Flamingo. Buy it now. It’s inspiring, impressive and wonderful.

Oct 21 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Kathryn Bevis

Poetry review – FLAMINGO: Emma Storr is greatly impressed by a debut pamphlet from Kathryn Bevis

It’s a delight to review this debut pamphlet by Kathryn Bevis. Flamingo contains 31 poems of extraordinary bravery, variety and skill. Bevis’s wit and inventiveness shine through, even when dealing with painful subjects such as a cancer diagnosis.

The pamphlet opens with the splendid ‘Wonder Woman Questions her Status as a ‘70’s Symbol of Female Empowerment’. The objectification of the female body and intrusive male gaze is cleverly explored in surprising imagery:

After describing the degradation she endures in comparison to Spiderman and Superman, Wonder Woman becomes more vocal in her demands. The poem ends viscerally and defiantly:

Bevis often employs the surreal to give us refreshing and new perspectives on serious societal problems. The dark humour in both “Teddy” and “The Smuggler” is chilling and adds to the impact of these poems featuring deeply disturbing male behaviour towards women. “Teddy” has an arresting first line: ‘Delia suspected that her teddy bear was gaslighting her’. In stanza three we learn:

Teddy’s comments, italicised throughout the poem, demonstrate his insidious power over Delia. Unlike Wonder Woman, who rebels, Delia seems to accept Teddy’s viewpoint and by the end has been completely brainwashed.

Humour is also used subtly to highlight the pressure placed on women to have children. In “Matryoshka” the text is arranged on the page to mirror the seven Russian dolls stacked inside each other and diminishing in size. The narrator is smug about their ability to each produce another daughter, a ‘pretty chick’, apart from the smallest doll who ‘was born with no space / inside. That’s right’. We are told that the other six dolls don’t judge her, but there’s an implicit criticism of a female who is unable to have children. On the opposite page to “Matryoshka” is the poem “In which I imagine my aborted foetus sings to me”, a juxtaposition that emphasises the loss experienced when choosing not to become a parent. The foetus sings in lyrical, broken verse:

listen to me i have known paradise have learned by heart your heartbeat’s songThe poem ends on a powerful metaphor that encapsulates both the umbilical connection between mother and child and also the idea of heritage:

i was your well-wound spool your coil of line that bindsA different use of textile imagery emerges in the poem “Knitting Nan Nan”. Grandma gradually take shape as the narrator knits her slippers in ‘shabby, worsted wool’ and then moves up Nan Nan’s body:

The detailed description of Nan Nan’s legs, trunk and bingo wings before these lines means we have a clear image of her. The gap between stanzas at this point adds to the shock of learning about the breast cancer. Nan Nan then ‘casts herself off’:

The ‘acrylic’ recalls the ‘screeching’ dress we were introduced to earlier. “Knitting Nan Nan” also demonstrates Bevis’s skill in using the senses of touch, hearing and sight to paint a tender portrait of a much-loved grandmother.

An interesting use of negatives is evident in the poems “Miss means both Mother and No-one” and “In this poem, your routine bloods have come back normal”. In the first of these there is a long list of reasons why the trainee teacher is not crying which builds up the tension for the reader to find out what is really going on. Eventually we are told she is crying for ‘let’s-call-him Jaydon, Ahmed, Tom’ or later ‘let’s-call-her Aisha, Kayla, Kim’ who, in different ways, have all exhibited desperate cries for help. The list of names showing us how many children are being failed by society on a regular basis, adds to the hopelessness of the situation.

Another list of negatives appears in a different context in “In this poem, your bloods have come back normal”. The speaker addresses an unidentified person, (possibly her mother) and imagines an alternative to the reality of cancer. Her constant denial underlines the fear felt both by the cancer sufferer and by the speaker when waiting for test results:

The final stanza ends ominously:

Flamingo concludes with a sequence of poems that demonstrate Bevis’s bravery, both in the content matter (a cancer diagnosis) and in the imaginative use of metaphor and imagery. The poetry is very moving without ever being maudlin. We read about the speaker’s appreciation of the natural world and of her partner, Ollie. “This” is a short poem of three stanzas, all of which end with the line ‘Nothing is worth more than this day’. The repetition works well to suggest time is running out and every moment must be savoured. The lyrical descriptions of the landscape, birds, light on water and the breeze sing on the page:

The poem “My Cancer as a Ring-Tailed Lemur” uses the energy and unpredictability of this animal to characterise the way cancer spreads and the difficulty of ‘catching’ it on different scans – ultrasound, then MRI and finally PET-CT.

The narrator and the lemur cohabit but the treatment for cancer is destroying their habitat, the body. They are both fighting ‘a forest fire’ that ultimately will destroy them.

The final poem in the pamphlet ‘Flamingo’ is a mix of deep sadness and something verging on the glorious. It starts ‘My love, when I die, I’ll turn flamingo:’ The second stanza reassures:

The assonance of ‘repose’ and ‘poise’ add to the sense of an invocation, a peaceful place.

In the final stanza, the flamingos are enjoying themselves. The afterlife seems an attractive place where ‘the dead all flock / together.’

We are brought back to reality and to the poignant message at the end of the poem:

I don’t think I have ever reviewed such a stunning and original pamphlet as Flamingo. Buy it now. It’s inspiring, impressive and wonderful.