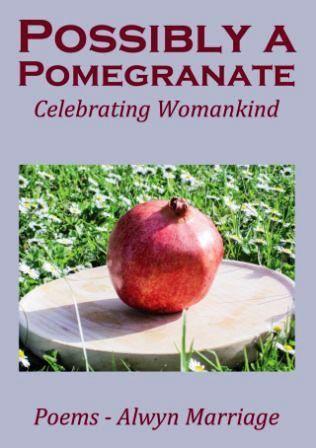

Poetry review – POSSIBLY A POMEGRANATE: Pat Edwards welcomes Alwyn Marriage’s new collection which is subtitled Celebrating Womankind

Possibly a Pomegranate

Alwyn Marriage

Palewell Press

ISBN 978-1-911587-61-3

£9.99

Possibly a Pomegranate

Alwyn Marriage

Palewell Press

ISBN 978-1-911587-61-3

£9.99

The pomegranate, or ‘seeded apple’, is traditionally known across many cultures in connection with prosperity, ambition and fertility. Alwyn Marriage actually makes reference in the title poem to another belief, that the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden was not in fact an apple but maybe a pomegranate. This mischievousness and slant view of how women are portrayed in historical and social contexts is a recurring theme throughout the collection. Marriage has divided the poems into sections which help guide the reader through the ages of womanhood, from childhood ‘Somewhere a child…’, right through to the reflective older woman. However, these are not hard and fast divisions as the poet is careful to show how the generations live together and sometimes learn from one another:

unite me

with generations of incredulous women

who learned from the wisdom of their grandchildren

that they were on their way to growing old.

(‘Skin – Phoebe’)

In ‘The cruelty of schoolgirls’ Marriage regrets the name-calling of her youth, admitting that she “was a schoolgirl bitch” who used to “fan the flames” of unkind mockery. This is quickly followed by an awakening of sensitivity in ‘Ski scene’, where her “eyes are suddenly opened” when she witnesses the courage of a young skier. This philosophical tone is present in many of the poems, offering a reflective wisdom about situations and encounters.

In the section called ‘Primrose Time’, it seems to me that this is a period of growth and exploration for the woman or women depicted. They are going out into the world, discovering art, men, relationships, foreign travel. However, the poet reflects here on inequality of opportunity, patriarchy and the nature of a woman’s role in different cultures.

The next section, ‘Woman in the Mirror’, continues the journey and offers the view from a maturing feminine perspective. ‘Finger four’ is a rather lovely, if wistful, consideration of “half a century/of wear and tear and faithfulness”, as a woman remembers how a fishhook belonging to a young admirer scarred her ring finger long ago, before she married her husband. There are poems about women in war zones, women weeping for their children, women growing older.

This leads us, of course, to the portrayal of older women in the section named ‘criss-cross the labyrinth’, in which we encounter plenty of looking back, the emergence of dementia and death:

But as old age begins

its insidious decline

towards what we all know

must be the end of ends,

we hold each day as dear,

look back along the path

we’ve travelled, try not to notice

that the finishing line is near.

I feel Marriage writes with unapologetic sentimentality at times, and that her best work is when she avoids this and gives us instead little gems of observation such as in ‘Childproof’, where the woman who has been through so much is undone by her failing physical strength:

But what finally drove her to distraction,

persuaded her that she was old and feeble,

was her inability to open jars and bottles.

Similarly, in ‘Losing it’, Marriage presents a moving account of a man for whom “the thread of his reality/unravelled in the fog and fury/that was closing in on him.” There are further poems about the death of an elderly woman in care and about the sadness of losing the sense of smell:

we wondered

whether aromatherapy might work;

if there was anything that could restore

olfactory satisfaction.

The final section of the collection is ‘Winds of History’, in which Marriage offers a glimpse of the female through the eyes of historical characters. In ‘Sappho’, which references the ancient Greek lyric poet widely regarded as a lesbian, the reader is invited to think about the loneliness of old age when “youth, fame and love now all flown/and you have gone.” In ‘Venus of Willendorf” Marriage suggests that the statue “full-bellied” and with “full-breasted exuberance” is a fitting celebration of “fecundity”. Elsewhere, Marriage explores the power play between Cleopatra and Mark Anthony and reflects in two poems – one a sonnet – on Lot and his wife who was turned to salt for looking back. Marriage also muses about the women living along Hadrian’s Wall and wonders whether friends writing to one another can make their “gentle unimportant words… last for ever.” There are other women protagonists too, including Hildegard, Eleanor, Austen, Grace Darling, Rosa Parks, all utilised as a means to celebrate strong women.

I think the reader can be left in no doubt that the poems are based both on elements of lived experience and on content that has been carefully researched. The result is a solid body of work in celebration of women. This is a confident blend of easy to read poems, unimpaired by heavy metaphor and overblown language, and there’s something rather refreshing about that.

Oct 20 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Alwyn Marriage

Poetry review – POSSIBLY A POMEGRANATE: Pat Edwards welcomes Alwyn Marriage’s new collection which is subtitled Celebrating Womankind

The pomegranate, or ‘seeded apple’, is traditionally known across many cultures in connection with prosperity, ambition and fertility. Alwyn Marriage actually makes reference in the title poem to another belief, that the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden was not in fact an apple but maybe a pomegranate. This mischievousness and slant view of how women are portrayed in historical and social contexts is a recurring theme throughout the collection. Marriage has divided the poems into sections which help guide the reader through the ages of womanhood, from childhood ‘Somewhere a child…’, right through to the reflective older woman. However, these are not hard and fast divisions as the poet is careful to show how the generations live together and sometimes learn from one another:

unite me with generations of incredulous women who learned from the wisdom of their grandchildren that they were on their way to growing old. (‘Skin – Phoebe’)In ‘The cruelty of schoolgirls’ Marriage regrets the name-calling of her youth, admitting that she “was a schoolgirl bitch” who used to “fan the flames” of unkind mockery. This is quickly followed by an awakening of sensitivity in ‘Ski scene’, where her “eyes are suddenly opened” when she witnesses the courage of a young skier. This philosophical tone is present in many of the poems, offering a reflective wisdom about situations and encounters.

In the section called ‘Primrose Time’, it seems to me that this is a period of growth and exploration for the woman or women depicted. They are going out into the world, discovering art, men, relationships, foreign travel. However, the poet reflects here on inequality of opportunity, patriarchy and the nature of a woman’s role in different cultures.

The next section, ‘Woman in the Mirror’, continues the journey and offers the view from a maturing feminine perspective. ‘Finger four’ is a rather lovely, if wistful, consideration of “half a century/of wear and tear and faithfulness”, as a woman remembers how a fishhook belonging to a young admirer scarred her ring finger long ago, before she married her husband. There are poems about women in war zones, women weeping for their children, women growing older.

This leads us, of course, to the portrayal of older women in the section named ‘criss-cross the labyrinth’, in which we encounter plenty of looking back, the emergence of dementia and death:

I feel Marriage writes with unapologetic sentimentality at times, and that her best work is when she avoids this and gives us instead little gems of observation such as in ‘Childproof’, where the woman who has been through so much is undone by her failing physical strength:

Similarly, in ‘Losing it’, Marriage presents a moving account of a man for whom “the thread of his reality/unravelled in the fog and fury/that was closing in on him.” There are further poems about the death of an elderly woman in care and about the sadness of losing the sense of smell:

The final section of the collection is ‘Winds of History’, in which Marriage offers a glimpse of the female through the eyes of historical characters. In ‘Sappho’, which references the ancient Greek lyric poet widely regarded as a lesbian, the reader is invited to think about the loneliness of old age when “youth, fame and love now all flown/and you have gone.” In ‘Venus of Willendorf” Marriage suggests that the statue “full-bellied” and with “full-breasted exuberance” is a fitting celebration of “fecundity”. Elsewhere, Marriage explores the power play between Cleopatra and Mark Anthony and reflects in two poems – one a sonnet – on Lot and his wife who was turned to salt for looking back. Marriage also muses about the women living along Hadrian’s Wall and wonders whether friends writing to one another can make their “gentle unimportant words… last for ever.” There are other women protagonists too, including Hildegard, Eleanor, Austen, Grace Darling, Rosa Parks, all utilised as a means to celebrate strong women.

I think the reader can be left in no doubt that the poems are based both on elements of lived experience and on content that has been carefully researched. The result is a solid body of work in celebration of women. This is a confident blend of easy to read poems, unimpaired by heavy metaphor and overblown language, and there’s something rather refreshing about that.