Paul McDonald reviews Seren’s new two-volume edition of Peter Finch’s Collected Poems

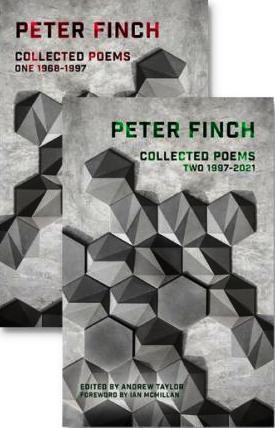

Collected Poems

Volume One (1968-1997) & Volume Two (1997-2021)

Peter Finch (edited by Andrew Taylor)

Seren

ISBN-13: 9781781726709; ISBN-13: 9781781726716

£19.99 each (£30 when purchased together from the publisher)

Collected Poems

Volume One (1968-1997) & Volume Two (1997-2021)

Peter Finch (edited by Andrew Taylor)

Seren

ISBN-13: 9781781726709; ISBN-13: 9781781726716

£19.99 each (£30 when purchased together from the publisher)

Poet, psychogeographer, and hero of the Welsh avant garde, Peter Finch is a writer for whom the phrase ‘force of nature’ could have been invented. Come to think of it, he probably invented it himself, or spliced it together in a cut-up. Now in his mid-seventies, the shaven headed septuagenarian feels more culturally relevant than ever, not least because of his verve and iconoclasm. If, like him, you’ve an appetite for literary subversion, you’ll find his double volume Collected Poems good enough to eat.

The books begin at the beginning, so I will too. Like so many emerging poets in the 60s, Finch was inspired by Ginsberg’s “Howl”’, together with The Mersey Sound poets, McGough, Patten, and Henri. Their writing gave him permission to exist outside the literary establishment, and instilled a desire to create his own poetry magazine, the Second Aeon, which launched in 1966. Initially little more than a showcase for his own work, it ran for 21 issues, becoming hugely influential. It brought him into contact with a broad range of writers, including concrete poet Sylvester Houédard, proto-postmodernist Nicholas Zurbrugg, and sound poets like Henri Chopin and Bob Cobbing. Their influence can be seen in Finch’s early works like Antarktika, ‘the visual score for, and transcription from a sound-text composition made on a stereophonic cassette recorder’, and Blats, ‘a collection of none poems’, whose composition involves chance, which, Finch reminds us in his original introduction, ‘is the natural order of things’. Such experimentation is well represented in both volumes of Collected Poems, which are characterised by Seren’s high production values. One of my favourite visual poems from volume one, for instance, is “Walking”, a tribute to the poet Eric Mottram created by photocopying Mottram’s Selected Poems onto a single sheet and then manipulating the text. As Andrew Taylor tells us, ‘Finch then inserts Mottram himself into the new Snowdonia-like textscape as a red dot’. In the original publication, Finch avoided the cost of colour printing by adding the red dots by hand, but Seren has a bigger budget and a broader palette, and Mottram enjoys a more permanent position on the printed page. It’s a striking image that I’ve looked at so many times that my copy now falls open to reveal a red dot ascending a mountain of semi-obliterated text.

Experimentation pervades both volumes, but sits alongside a wealth of accessible material. In one interview Finch says that, when it comes to a poet’s relationship with the public, ‘The trick is to avoid impenetrability and get the balance right’, and I think he manages to do that in much of his writing. While he frequently covers difficult territory, and some of his work is cryptic in the extreme, you can’t help but be struck by the creative intelligence behind it, and the sense that he has our best interests at heart. Bob Cobbing had a word for Finch’s aesthetic – ‘verbivocovisual’ – which is appropriate in that, while you often need to see and/or hear his work in order to fully appreciate it, much can be consumed in the usual way. Indeed, the irreverence and intertextuality of Finch’s visual poems and cut-ups can be seen in his more conventional writing. Take, for example, “All I Need Is Three Plums”, which, as you may guess from the title, is in playful dialogue with William Carlos Williams. It opens:

I have sold your jewellery collection,

which you kept in a box, forgive me.

I am sorry, but it came upon me

and the money was so inviting, so sweet

and so cold.

I like the way this exposes the moral implications of Williams’s “This is Just To Say”, forcing us to reflect on the nature of trust, theft, transgression and forgiveness. It transforms the impact of the speaker’s plea to be forgiven, and the language employed to justify his behaviour. It closes:

Please forgive me, I have taken the money

you have been saving in the ceramic pig

and spent it on drink, so sweet and inviting.

This is just to say I am in the pub

where I have purchased the fat guy from

Merthyr's entire collection of scratch and win.

All I need now is three delicious plums.

Forgive me, sweetie,

these things just happen.

I love the jokey references to the original, like the delightful reworking of the word ‘sweet’ in the final stanza, ‘Forgive me, sweetie’; it exposes the duplicity and latent hostility of Williams’s speaker, inviting us re-examine his professed contrition, reminding us that confessions are narratives designed to excuse the penitent.

Finch’s attitude to the literary canon is gloriously subversive, as can also be seen in his text message reworking of Wordsworth’s ‘Composed upon Westminster Bridge’:

‘N Wst Brdg’:

'nvr saw nvr flt clm so deep!!!

rvr flws at hs sweet wll (own):

Deer GD! vry hses seem slp | |

+ all tht BIG HRT lyng still!’

Again this is indicative of Finch’s playfulness, which is often overtly comic: if you’ve ever seen him read you’ll know that humour frequently combines with his infectious enthusiasm, making for powerful and often hilarious performances.

As a psychogeographer, Finch’s principal interest is Wales, and particularly his beloved Cardiff. He is the author of Real Cardiff 1, 2, and 3, together with Real Wales, among other place-based books, and hundreds of individual poems about the region. Again his poems about place range from the experimental to the conventional; Wales-themed list poems abound, for instance, such as “The City Region”, which lists Cardiff street names, and “Colon” which presents a list of Welsh battles. I’m particularly fond of his Zen Cymru haikus:

This Wales leaks there isn't one

That doesn't

Is there?

We can’t miss the homophonic pun, but there’s more to it than this. To me this poem is quintessentially Finchian, partly because of the humour, and partly because of its unwillingness to be reduced to a single meaning. The implication is that there isn’t a definition of Wales that doesn’t ‘leak’, in the sense that the place will always evade definitive descriptions. Finch persistently works against definition: his writing, just like his favourite subject of Wales, invariably refuses to be pinned down.

In his foreword to the second volume, Ian McMillan relates an anecdote about once inviting Finch to talk to a group of his students. McMillan told Finch that the class needed livening up, which the latter clearly took as a challenge. Having begun by reading a few conventional poems, Finch produced a copy of a Mills and Boon book and began reading from that. As he read he started tearing out the pages and eating them. McMillan considers this ‘a deep examination of the relationship of the writer and the reader, the performer and the audience’, which seems like a fair point. The ultimate meaning of such experiments remains elusive, of course, but the world is better for them. They have driven Finch’s art since the sixties, and while they don’t always find such radical expression as the literal consumption of printed text, they’re rarely predictable, or boring. You might say they’re what make both volumes of Collected Poems good enough to eat, and at close to 1000 pages it’s a copious repast.

Aug 6 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Peter Finch

Paul McDonald reviews Seren’s new two-volume edition of Peter Finch’s Collected Poems

Poet, psychogeographer, and hero of the Welsh avant garde, Peter Finch is a writer for whom the phrase ‘force of nature’ could have been invented. Come to think of it, he probably invented it himself, or spliced it together in a cut-up. Now in his mid-seventies, the shaven headed septuagenarian feels more culturally relevant than ever, not least because of his verve and iconoclasm. If, like him, you’ve an appetite for literary subversion, you’ll find his double volume Collected Poems good enough to eat.

The books begin at the beginning, so I will too. Like so many emerging poets in the 60s, Finch was inspired by Ginsberg’s “Howl”’, together with The Mersey Sound poets, McGough, Patten, and Henri. Their writing gave him permission to exist outside the literary establishment, and instilled a desire to create his own poetry magazine, the Second Aeon, which launched in 1966. Initially little more than a showcase for his own work, it ran for 21 issues, becoming hugely influential. It brought him into contact with a broad range of writers, including concrete poet Sylvester Houédard, proto-postmodernist Nicholas Zurbrugg, and sound poets like Henri Chopin and Bob Cobbing. Their influence can be seen in Finch’s early works like Antarktika, ‘the visual score for, and transcription from a sound-text composition made on a stereophonic cassette recorder’, and Blats, ‘a collection of none poems’, whose composition involves chance, which, Finch reminds us in his original introduction, ‘is the natural order of things’. Such experimentation is well represented in both volumes of Collected Poems, which are characterised by Seren’s high production values. One of my favourite visual poems from volume one, for instance, is “Walking”, a tribute to the poet Eric Mottram created by photocopying Mottram’s Selected Poems onto a single sheet and then manipulating the text. As Andrew Taylor tells us, ‘Finch then inserts Mottram himself into the new Snowdonia-like textscape as a red dot’. In the original publication, Finch avoided the cost of colour printing by adding the red dots by hand, but Seren has a bigger budget and a broader palette, and Mottram enjoys a more permanent position on the printed page. It’s a striking image that I’ve looked at so many times that my copy now falls open to reveal a red dot ascending a mountain of semi-obliterated text.

Experimentation pervades both volumes, but sits alongside a wealth of accessible material. In one interview Finch says that, when it comes to a poet’s relationship with the public, ‘The trick is to avoid impenetrability and get the balance right’, and I think he manages to do that in much of his writing. While he frequently covers difficult territory, and some of his work is cryptic in the extreme, you can’t help but be struck by the creative intelligence behind it, and the sense that he has our best interests at heart. Bob Cobbing had a word for Finch’s aesthetic – ‘verbivocovisual’ – which is appropriate in that, while you often need to see and/or hear his work in order to fully appreciate it, much can be consumed in the usual way. Indeed, the irreverence and intertextuality of Finch’s visual poems and cut-ups can be seen in his more conventional writing. Take, for example, “All I Need Is Three Plums”, which, as you may guess from the title, is in playful dialogue with William Carlos Williams. It opens:

I like the way this exposes the moral implications of Williams’s “This is Just To Say”, forcing us to reflect on the nature of trust, theft, transgression and forgiveness. It transforms the impact of the speaker’s plea to be forgiven, and the language employed to justify his behaviour. It closes:

I love the jokey references to the original, like the delightful reworking of the word ‘sweet’ in the final stanza, ‘Forgive me, sweetie’; it exposes the duplicity and latent hostility of Williams’s speaker, inviting us re-examine his professed contrition, reminding us that confessions are narratives designed to excuse the penitent.

Finch’s attitude to the literary canon is gloriously subversive, as can also be seen in his text message reworking of Wordsworth’s ‘Composed upon Westminster Bridge’:

Again this is indicative of Finch’s playfulness, which is often overtly comic: if you’ve ever seen him read you’ll know that humour frequently combines with his infectious enthusiasm, making for powerful and often hilarious performances.

As a psychogeographer, Finch’s principal interest is Wales, and particularly his beloved Cardiff. He is the author of Real Cardiff 1, 2, and 3, together with Real Wales, among other place-based books, and hundreds of individual poems about the region. Again his poems about place range from the experimental to the conventional; Wales-themed list poems abound, for instance, such as “The City Region”, which lists Cardiff street names, and “Colon” which presents a list of Welsh battles. I’m particularly fond of his Zen Cymru haikus:

We can’t miss the homophonic pun, but there’s more to it than this. To me this poem is quintessentially Finchian, partly because of the humour, and partly because of its unwillingness to be reduced to a single meaning. The implication is that there isn’t a definition of Wales that doesn’t ‘leak’, in the sense that the place will always evade definitive descriptions. Finch persistently works against definition: his writing, just like his favourite subject of Wales, invariably refuses to be pinned down.

In his foreword to the second volume, Ian McMillan relates an anecdote about once inviting Finch to talk to a group of his students. McMillan told Finch that the class needed livening up, which the latter clearly took as a challenge. Having begun by reading a few conventional poems, Finch produced a copy of a Mills and Boon book and began reading from that. As he read he started tearing out the pages and eating them. McMillan considers this ‘a deep examination of the relationship of the writer and the reader, the performer and the audience’, which seems like a fair point. The ultimate meaning of such experiments remains elusive, of course, but the world is better for them. They have driven Finch’s art since the sixties, and while they don’t always find such radical expression as the literal consumption of printed text, they’re rarely predictable, or boring. You might say they’re what make both volumes of Collected Poems good enough to eat, and at close to 1000 pages it’s a copious repast.