Poetry review – THE FIELD OF HAPPINESS: Robert Cooperman is pretty happy with Charles Rammelkamp’s new collection

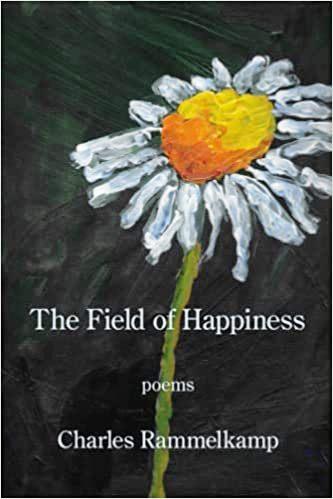

The Field of Happiness

Charles Rammelkamp

Kelsay Books

ISBN 978-1639801268

152 pp $19.00

The Field of Happiness

Charles Rammelkamp

Kelsay Books

ISBN 978-1639801268

152 pp $19.00

The epigraph for the introductory poem in Charles Rammelkamp’s marvelous new collection is from Aristotle: “Happiness is the meaning and the purpose of life, the whole aim and end of human existence.” Happiness is at the core of The Field of Happiness, its vagaries, its fleeting nature, the memory of happiness, the impossibility of sustaining it for more than a very short time, while life and time keep churning away at us, or as Rammelkamp states in “An Expert in the Field of Happiness,”

I am reasonably content

a solid thirty-year marriage,

two wonderful daughters,

friends and family for which I am grateful,

comfortable financially,

my health OK for a sexagenarian.

But an expert in Happiness?

Are you kidding?

From there, Rammelkamp gives us a tour, in both personal and persona poems, of the whole human experience, not just our search for happiness. In the first section, “The Smell of Chlorine,” we’re presented with celebrity and fame, those who have it and those who want to get close to it or have been close to it. In “Celebrity,” we fleetingly meet Eddie, through the narrator’s eyes, in the locker room of Baltimore’s Downtown Athletic Club. He tells the protagonist, “I taught Oprah how to swim,” which leads the “I” of the poem to reminisce that the closest he ever got to fame was knowing a kid in high school who became a studio musician and who played “on one of Mick Jagger’s solo albums.” From there, he jumps to his daughter, who knew a girl who was a contestant on the TV reality show, So You Think You Can Dance? The narrator concludes with this trenchant observation: “Fame clings close/when you get next to it,/like the smell of chlorine/on the skin/after the swimming pool.” There’s an implicit judgement there, but it’s deliciously ambiguous. We think fame and celebrity will make us happy, even at second hand, and like chlorine it’s both salutary, but carries its own distinct, eye tearing odor.

Of course fame also has its dangers, as in “In the Clearing Stands a Boxer,” which tells of Salamo Arouch, the Jewish All-Balkans Middleweight Champion who was forced by the Nazis to battle for his life in Auschwitz. His family perished, but he survived by more or less boxing to the death other boxers, for the sadistic pleasure of the Nazis. I’ll leave it to your imagination if he was ever a happy man thereafter, especially since Rammelkamp uses an effective allusion to the great Simon and Garfunkel song, “The Boxer”:

still standing, if bloodied, scarred,

after the final bell,

but you can bet he’d carry the reminders

of his anger and his shame

until the day he died in 2009

This poem, it seems to me, sets up the rest of the collection, which details moments of happiness and long-lasting bouts of its opposite. In “Freitod,” for instance our traveling narrator overhears a conversation between two women in a Chick-fil-A, one of them lamenting that her ex hasn’t paid “no child support/for three-five months,” her companion offering, “he ain’t got no job.” Then the second unleashes on one of her kids: “Hey Lonzo, quit messin’ around!” Hearing that, all the narrator can do is leave, no longer hungry, but grateful that his relatively contented home and family are a mere hundred miles away.

But for many of the poems and narrators in this lovely collection, happiness, or at least its pursuit, resides in sex and love. For many of the teenage protagonists, it’s the realization that the object of their affection and/or lust, is out of reach, though sometimes there’s an unexpected payday for being the wrong guy at the right time, as in “The Rusty Studebaker,” which is the companion piece and male version of “Backseat Blues”. In “Studebaker”, we have an interesting triangle: on teenage joyride Friday nights, the narrator has to sit in the backseat with Mikey and Kelly, the girlfriend of Nick, who, as alpha male, gets to ride shotgun. But Kelly wants revenge on Nick, for more or less ignoring her on these rites of teenage passage with too much beer and not enough brains. So while the protagonist and Kelly are in the dark of the backseat, in the hidden darkness, and Mikey seems conveniently oblivious, the narrator’s hand sneaks under Kelly’s shirt, while she lays a hand on his thigh, and things progress to his twirling “Kelly’s nipples between forefinger and thumb,/my lust thick as a swamp.” But the narrator knows this is going nowhere, that Kelly will stay with Nick, and after the narrator is dropped off at his parents’ home, he groans all night.

But to return to the question, where does happiness reside? For many of the characters and for Rammelkamp, too, the clearest answer is in memories of the past, when he was a kid and all of his immediate family were still alive and he thought life would continue like that forever. There are several poems in which Rammelkamp fondly remembers both parents, but the one I want to end on is “What I Enjoyed,” in which, on his morning commute, he hears “a railroad maintenance guy” whistling a song that sounds vaguely familiar. When Rammelkamp arrives at his stop in the never stated as such, but implied ominous Wall Street area, it finally hits him that it’s a song his mother used to sing while driving him to school when he was a kid. He starts singing it as well, happy in the memory:

Stepping into the bustle of the financial district,

I can still see her

behind the wheel of the beige Dodge Dart

back home in Potawatomi Falls, Michigan

So in the only way possible, through memory, he can go home again to his happy memories of childhood and youth.

This is a marvelous, unsentimental look back, and also forward to the inevitable. In a way it’s like the tacit lesson of biographies and memoirs, but told in wonderfully straightforward, no nonsense, poetry: it’s not that we all die that matters, it’s how we’ve lived.

Robert Cooperman, author, most recently of Go Play Outside (Apprentice House) and winner of the Colorado Book Award for Poetry, for In The Colorado Gold Fever Mountains

May 12 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Charles Rammelkamp

Poetry review – THE FIELD OF HAPPINESS: Robert Cooperman is pretty happy with Charles Rammelkamp’s new collection

The epigraph for the introductory poem in Charles Rammelkamp’s marvelous new collection is from Aristotle: “Happiness is the meaning and the purpose of life, the whole aim and end of human existence.” Happiness is at the core of The Field of Happiness, its vagaries, its fleeting nature, the memory of happiness, the impossibility of sustaining it for more than a very short time, while life and time keep churning away at us, or as Rammelkamp states in “An Expert in the Field of Happiness,”

From there, Rammelkamp gives us a tour, in both personal and persona poems, of the whole human experience, not just our search for happiness. In the first section, “The Smell of Chlorine,” we’re presented with celebrity and fame, those who have it and those who want to get close to it or have been close to it. In “Celebrity,” we fleetingly meet Eddie, through the narrator’s eyes, in the locker room of Baltimore’s Downtown Athletic Club. He tells the protagonist, “I taught Oprah how to swim,” which leads the “I” of the poem to reminisce that the closest he ever got to fame was knowing a kid in high school who became a studio musician and who played “on one of Mick Jagger’s solo albums.” From there, he jumps to his daughter, who knew a girl who was a contestant on the TV reality show, So You Think You Can Dance? The narrator concludes with this trenchant observation: “Fame clings close/when you get next to it,/like the smell of chlorine/on the skin/after the swimming pool.” There’s an implicit judgement there, but it’s deliciously ambiguous. We think fame and celebrity will make us happy, even at second hand, and like chlorine it’s both salutary, but carries its own distinct, eye tearing odor.

Of course fame also has its dangers, as in “In the Clearing Stands a Boxer,” which tells of Salamo Arouch, the Jewish All-Balkans Middleweight Champion who was forced by the Nazis to battle for his life in Auschwitz. His family perished, but he survived by more or less boxing to the death other boxers, for the sadistic pleasure of the Nazis. I’ll leave it to your imagination if he was ever a happy man thereafter, especially since Rammelkamp uses an effective allusion to the great Simon and Garfunkel song, “The Boxer”:

This poem, it seems to me, sets up the rest of the collection, which details moments of happiness and long-lasting bouts of its opposite. In “Freitod,” for instance our traveling narrator overhears a conversation between two women in a Chick-fil-A, one of them lamenting that her ex hasn’t paid “no child support/for three-five months,” her companion offering, “he ain’t got no job.” Then the second unleashes on one of her kids: “Hey Lonzo, quit messin’ around!” Hearing that, all the narrator can do is leave, no longer hungry, but grateful that his relatively contented home and family are a mere hundred miles away.

But for many of the poems and narrators in this lovely collection, happiness, or at least its pursuit, resides in sex and love. For many of the teenage protagonists, it’s the realization that the object of their affection and/or lust, is out of reach, though sometimes there’s an unexpected payday for being the wrong guy at the right time, as in “The Rusty Studebaker,” which is the companion piece and male version of “Backseat Blues”. In “Studebaker”, we have an interesting triangle: on teenage joyride Friday nights, the narrator has to sit in the backseat with Mikey and Kelly, the girlfriend of Nick, who, as alpha male, gets to ride shotgun. But Kelly wants revenge on Nick, for more or less ignoring her on these rites of teenage passage with too much beer and not enough brains. So while the protagonist and Kelly are in the dark of the backseat, in the hidden darkness, and Mikey seems conveniently oblivious, the narrator’s hand sneaks under Kelly’s shirt, while she lays a hand on his thigh, and things progress to his twirling “Kelly’s nipples between forefinger and thumb,/my lust thick as a swamp.” But the narrator knows this is going nowhere, that Kelly will stay with Nick, and after the narrator is dropped off at his parents’ home, he groans all night.

But to return to the question, where does happiness reside? For many of the characters and for Rammelkamp, too, the clearest answer is in memories of the past, when he was a kid and all of his immediate family were still alive and he thought life would continue like that forever. There are several poems in which Rammelkamp fondly remembers both parents, but the one I want to end on is “What I Enjoyed,” in which, on his morning commute, he hears “a railroad maintenance guy” whistling a song that sounds vaguely familiar. When Rammelkamp arrives at his stop in the never stated as such, but implied ominous Wall Street area, it finally hits him that it’s a song his mother used to sing while driving him to school when he was a kid. He starts singing it as well, happy in the memory:

So in the only way possible, through memory, he can go home again to his happy memories of childhood and youth.

This is a marvelous, unsentimental look back, and also forward to the inevitable. In a way it’s like the tacit lesson of biographies and memoirs, but told in wonderfully straightforward, no nonsense, poetry: it’s not that we all die that matters, it’s how we’ve lived.

Robert Cooperman, author, most recently of Go Play Outside (Apprentice House) and winner of the Colorado Book Award for Poetry, for In The Colorado Gold Fever Mountains