THE FACT OF MEMORY: Charles Rammelkamp browses a collection of essays by Aaron Angello

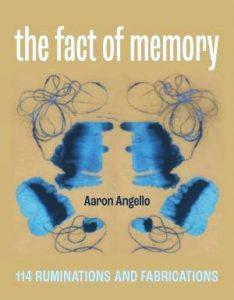

The Fact of Memory

Aaron Angello

Rose Metal Press, 2022

ISBN: 978-1-941628-25-6

132 pp $15.95

The Fact of Memory

Aaron Angello

Rose Metal Press, 2022

ISBN: 978-1-941628-25-6

132 pp $15.95

Subtitled 114 Ruminations and Fabrications, Aaron Angello’s intriguing collection of short prose essays takes off from William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29, which consists of exactly 114 words. Each essay is titled by each of these words, in order. The sonnet begins, “When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes….” The speaker of the poem laments his current state of affairs in the first eight lines (he looks “upon myself and curse my fate”), but in the final six lines, beginning with the thought, “Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,” he takes solace in the memory of his beloved’s affection. The poem ends:

For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

The one-hundred and fourteen essays start with “When,” “in,” and “disgrace” and conclude with “state,” “with,” and “kings.” Note that memory is central to the sonnet’s message. Of course, as Angello writes in the Author’s Note that opens this unique collection, “The fact of memory, one might say, is that it is never quite factual.”

In the Author’s Note, Angello describes the genesis of this work. “I wrote, in order, a single word from Shakespeare’s 29th sonnet. I sat in a chair, looked at the word for that day, then for several minutes I just thought about it, completely out of its context.” And then he began to write, without paying attention to whether he was writing a story, an essay, a prose poem. It just had to be prose, and he had to fill a page. After completing the 114 pieces, he set the manuscript aside before returning to it for the process of reflection and revision.

The resulting work is a curious puzzle, a jigsaw of thoughts. For instance, the word “I” appears four times in Shakespeare’s poem (words 9, 59, 72 and 107). The writing swings from a scene in a café in Paris (“Rimbaud said, ‘Je est un autre,’” the first piece begins – “I is an other”) to a presumably fictional memory – “I once slept with a very pretty woman in Rick Springfield’s bed” (the two were stunt people) – and then meanders to Costa Rica. Number 72 is about a guy who works in a big-box chain bookstore in Denver, who decides to “do something extraordinary.” (He brushes his teeth, puts on a bathrobe and sits down at his kitchen table.) Number 107 begins:

From Narcissus to the greedy dog with the bone, stories have taught us to avoid reflection.

Yet here I am, examining every inch of myself in the pages of this book.

“I wanted to access a mental space that allowed for spontaneity,” is how Angello explains his process. Reading the essays becomes a captivating exercise in trying to understand the impulse behind the words. The word “man’s” appears twice, for instance – #51 and #55 – the first beginning, “My bathroom is filled with gender specific products,” and the second, “I watch an old man’s hands shaking in his lap.” A man’s grooming products, a man’s hands. Number 111, “My,” begins,

My phone. My spate of absences. My imagination. My catalogue. My ever-growing collection

of Raymond Chandler novels. My sympathies. My dog. My sense of self-worth coupled with

my debilitating insecurity,

and it continues this way for the entire page, concluding,

My fear of success. My brothers. My insurance policy. My second-hand couch. My mystery.

My composition. My construction.

Ah! we might think, I get it! The possessive.

Number 81, “To”: “A man tosses a ball to his daughter. A soldier is sent to Kandahar. A rover lands on Mars. Hand moves to cheek. Thumb to lip.”

The word “essay” means “attempt,” a form created in the sixteenth century by Michel de Montaigne, who coined the term. Just as Montaigne’s stated goal was to describe himself with utter frankness and honesty (“bonne foi”), to be “introspective,” so Angello’s riffs are meant to let his imagination wander on its own – or rather not “meant”; nothing is “intended.” He just sees where his thoughts lead him, from the springboard of the daily word. Nearly all of these pieces fill most of a single page, but the sixty-first, “Enjoy,” is a single sentence: “Coca-Cola trademarked the slogan ‘Enjoy’ a long time ago. It is a directive.”

Of course, we’ve been warned not to take any of these thoughts as “facts,” but still, we know the author is a poet and playwright, and we have to wonder how much is purely fictional (did he once make love to a woman in Rick Springfield’s bed?) and how much rooted in real experience. Number 57, “With,” begins: “The first job I got when I moved from New York to Los Angeles involved dressing up as a pirate and sword fighting at children’s birthday parties.” We also ask ourselves, does it matter if any of these “memories” are “true”? So many of these scenes take place in New York and in Los Angeles. It must be a fact that the author has indeed lived in these cities, and his memory takes him there, reliable or unreliable as that memory might be.

“Deep in a middle-aged man’s memory,” the final piece, “Kings,” begins, “a six-year-old boy is playing beneath the branches of a quaking aspen in his backyard.” If the facticity of memory is indeed at issue in these charming essays, as the author suggests, this very sentence may be the key to it all. Time passes, “memories” evolve.

Apr 25 2022

THE FACT OF MEMORY

THE FACT OF MEMORY: Charles Rammelkamp browses a collection of essays by Aaron Angello

Subtitled 114 Ruminations and Fabrications, Aaron Angello’s intriguing collection of short prose essays takes off from William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29, which consists of exactly 114 words. Each essay is titled by each of these words, in order. The sonnet begins, “When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes….” The speaker of the poem laments his current state of affairs in the first eight lines (he looks “upon myself and curse my fate”), but in the final six lines, beginning with the thought, “Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,” he takes solace in the memory of his beloved’s affection. The poem ends:

The one-hundred and fourteen essays start with “When,” “in,” and “disgrace” and conclude with “state,” “with,” and “kings.” Note that memory is central to the sonnet’s message. Of course, as Angello writes in the Author’s Note that opens this unique collection, “The fact of memory, one might say, is that it is never quite factual.”

In the Author’s Note, Angello describes the genesis of this work. “I wrote, in order, a single word from Shakespeare’s 29th sonnet. I sat in a chair, looked at the word for that day, then for several minutes I just thought about it, completely out of its context.” And then he began to write, without paying attention to whether he was writing a story, an essay, a prose poem. It just had to be prose, and he had to fill a page. After completing the 114 pieces, he set the manuscript aside before returning to it for the process of reflection and revision.

The resulting work is a curious puzzle, a jigsaw of thoughts. For instance, the word “I” appears four times in Shakespeare’s poem (words 9, 59, 72 and 107). The writing swings from a scene in a café in Paris (“Rimbaud said, ‘Je est un autre,’” the first piece begins – “I is an other”) to a presumably fictional memory – “I once slept with a very pretty woman in Rick Springfield’s bed” (the two were stunt people) – and then meanders to Costa Rica. Number 72 is about a guy who works in a big-box chain bookstore in Denver, who decides to “do something extraordinary.” (He brushes his teeth, puts on a bathrobe and sits down at his kitchen table.) Number 107 begins:

“I wanted to access a mental space that allowed for spontaneity,” is how Angello explains his process. Reading the essays becomes a captivating exercise in trying to understand the impulse behind the words. The word “man’s” appears twice, for instance – #51 and #55 – the first beginning, “My bathroom is filled with gender specific products,” and the second, “I watch an old man’s hands shaking in his lap.” A man’s grooming products, a man’s hands. Number 111, “My,” begins,

and it continues this way for the entire page, concluding,

Ah! we might think, I get it! The possessive.

Number 81, “To”: “A man tosses a ball to his daughter. A soldier is sent to Kandahar. A rover lands on Mars. Hand moves to cheek. Thumb to lip.”

The word “essay” means “attempt,” a form created in the sixteenth century by Michel de Montaigne, who coined the term. Just as Montaigne’s stated goal was to describe himself with utter frankness and honesty (“bonne foi”), to be “introspective,” so Angello’s riffs are meant to let his imagination wander on its own – or rather not “meant”; nothing is “intended.” He just sees where his thoughts lead him, from the springboard of the daily word. Nearly all of these pieces fill most of a single page, but the sixty-first, “Enjoy,” is a single sentence: “Coca-Cola trademarked the slogan ‘Enjoy’ a long time ago. It is a directive.”

Of course, we’ve been warned not to take any of these thoughts as “facts,” but still, we know the author is a poet and playwright, and we have to wonder how much is purely fictional (did he once make love to a woman in Rick Springfield’s bed?) and how much rooted in real experience. Number 57, “With,” begins: “The first job I got when I moved from New York to Los Angeles involved dressing up as a pirate and sword fighting at children’s birthday parties.” We also ask ourselves, does it matter if any of these “memories” are “true”? So many of these scenes take place in New York and in Los Angeles. It must be a fact that the author has indeed lived in these cities, and his memory takes him there, reliable or unreliable as that memory might be.

“Deep in a middle-aged man’s memory,” the final piece, “Kings,” begins, “a six-year-old boy is playing beneath the branches of a quaking aspen in his backyard.” If the facticity of memory is indeed at issue in these charming essays, as the author suggests, this very sentence may be the key to it all. Time passes, “memories” evolve.