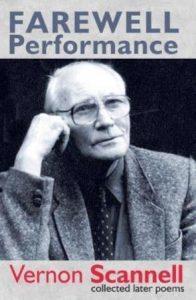

Poetry review – FAREWELL PERFORMANCE: Paul McDonald looks back with pleasure on the collected later poems of Vernon Scannell

Farewell Performance: Collected Later Poems

Vernon Scannell.

Smokestack Books

978-1838465339

312 pp £9.99

Farewell Performance: Collected Later Poems

Vernon Scannell.

Smokestack Books

978-1838465339

312 pp £9.99

We often hear of poets leading colourful lives, but one who genuinely did is the late Vernon Scannell (1922-2007). A war hero who took part in the D Day landings, he was also a deserter who spent time in an Egyptian military prison and a Birmingham mental institution. There aren’t many poets who can claim to have been professional boxers, but Scannell was one, earning money as a middleweight, and winning championships for Leeds University, before turning to full time writing. Scannell was a contradictory and controversial character: he had a reputation for heavy drinking and violence, but also possessed a capacity for compassion and a deep sensitivity. He is certainly a poet worth reading about, and those who’re interested could look at one of Scannell’s own memoirs, or, for a more objective view, James Andrew Taylor’s 2013 biography, Walking Wounded. Scannell had a long and prolific literary career, winning a hatful of accolades over the years, and a substantial Collected Poems appeared in 1993, containing most of his poetry up to that point. This new volume presents material written after ‘93, including his last six collections, and some uncollected poems. It’s a chunky book, supplemented with a preface from Martin Reed, an introduction from Alan Brownjohn, and a delightful reflection on the writer’s life from his friend and publisher Jeremy Robson.

Both in terms of themes and aesthetics, Farewell Performance resembles his earlier Collected Poems. His key preoccupations are all here, principally love, war, boxing and drinking, albeit with a greater emphasis on infirmity and mortality; likewise, his style remains typically accessible, marked as always by a flair for rhyming metrics, and a playful, often dark wit. John Carey once said that Scannell ‘nearly always works on two levels, one realistic and external, the other imaginative, metaphorical, haunted by memory and desire’, and this is evident throughout his later work. Consider ‘Missing Things’, for instance, which reflects on his house in relation to his own mortality:

I’ve lived here for so long it seems to be

a part of what I am, yet I’m aware

that when I’ve gone it won’t remember me

and I, of course, will neither know nor care

since, like the stone of which the house is made,

I’ll feel no more than it does light and air.

Then why so sad? And just a bit afraid?

Clearly what haunts Scannell is a fear of death akin to Larkin’s in ‘Aubade’. Scannell links his impending death to the house that will outlast him, and which represents what it means to be alive: the familiar domestic space that provides a context for his life. Because a house is made of stone, it ‘will neither know nor care’ about his demise, but from the human perspective it’s imbued with emotional weight, given meaning by his existence, like his own flesh and blood; thus the idea of a home being empty after death augments the fear of loss and oblivion (‘Not to be here,/Not to be anywhere’, as Larkin puts it). Elsewhere, such safe spaces are seen to be under threat, their status as safe havens undermined by conflict and darkness, as in the ironically titled ‘Safe Houses’, where bad news encroaches on the domestic sanctuary of the home, interrupting the ‘Scent of coffee and the radio’s/smoothly laundered voice’:

And here it comes: a car-bomb in Baghdad

kills forty-three; a sixteen-year-old lad

shoots woman constable dead;

Keele student raped and strangled in her room;

Russian miners’ workplace now their tomb;

Leeds pensioner stabbed in bed.

This litany of horrors haunts the speaker, despite his efforts to rationalise and make them safe, as suggested in the closing stanza:

And later in the morning, when he goes

along his quiet road to church, he knows

he won’t be mugged or shot;

but as he smiles, from somewhere out of sight

he hears the low and ominous growl which might

be thunder, or might not.

It’s said that Scannell was drawn to poetry after reading Walter de la Mare, and it’s easy to see similarities in style – both have a penchant for dramatic monologues for instance – but de la Mare often feels rather distant from his verse, whereas Scannell’s life and personality are frequently manifest. During the War, Scannell saw significant action, was shot in both legs while on patrol in France, and it doesn’t take a psychiatrist to locate the origin of the fear and paranoia discernible in ‘Safe Houses’. There’s frequently a ‘low and ominous growl’ in his work, which regularly builds to a dramatic climax. This can be seen particularly in poems which reference war directly, such as ‘A Few Words to the Not-So-Old’, which closes:

But certain memories will never die:

Tom Fenton’s smile, part naughty urchin’s

grin yet just a little sad,

before the bomb blew it and him star-high

near Mareth as our Company moved in

and the universe went mad.

It’s fair to say that Scannell’s sense of the universe as a ‘mad’ never completely left him. As Brownjohn says in his introduction, ‘The passing of time has done little or nothing to reduce the pain of having had to live through the experience of war’. The pain is writ large throughout much of his work, and he doesn’t spare us the details, as in war poems like ‘Robbie’ where the eponymous hero ‘Sucked on his rifle-muzzle like a straw’ and blew his brains out, or in a boxing poem like ‘It Should Be Easier’, which ends,

So, no matter what

they say about experience and the need

for skills that veterans alone have got,

how it gets easier, you know that it does not.

It didn’t get easier for Scannell, as these later poems attest; he is still, to use Carey’s words, ‘haunted by memory’, but this very often provides an edge – an authority and authenticity – that adds weight to his ostensibly light verse, making for an absorbing book that I read with great pleasure.

Apr 14 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Vernon Scannell

Poetry review – FAREWELL PERFORMANCE: Paul McDonald looks back with pleasure on the collected later poems of Vernon Scannell

We often hear of poets leading colourful lives, but one who genuinely did is the late Vernon Scannell (1922-2007). A war hero who took part in the D Day landings, he was also a deserter who spent time in an Egyptian military prison and a Birmingham mental institution. There aren’t many poets who can claim to have been professional boxers, but Scannell was one, earning money as a middleweight, and winning championships for Leeds University, before turning to full time writing. Scannell was a contradictory and controversial character: he had a reputation for heavy drinking and violence, but also possessed a capacity for compassion and a deep sensitivity. He is certainly a poet worth reading about, and those who’re interested could look at one of Scannell’s own memoirs, or, for a more objective view, James Andrew Taylor’s 2013 biography, Walking Wounded. Scannell had a long and prolific literary career, winning a hatful of accolades over the years, and a substantial Collected Poems appeared in 1993, containing most of his poetry up to that point. This new volume presents material written after ‘93, including his last six collections, and some uncollected poems. It’s a chunky book, supplemented with a preface from Martin Reed, an introduction from Alan Brownjohn, and a delightful reflection on the writer’s life from his friend and publisher Jeremy Robson.

Both in terms of themes and aesthetics, Farewell Performance resembles his earlier Collected Poems. His key preoccupations are all here, principally love, war, boxing and drinking, albeit with a greater emphasis on infirmity and mortality; likewise, his style remains typically accessible, marked as always by a flair for rhyming metrics, and a playful, often dark wit. John Carey once said that Scannell ‘nearly always works on two levels, one realistic and external, the other imaginative, metaphorical, haunted by memory and desire’, and this is evident throughout his later work. Consider ‘Missing Things’, for instance, which reflects on his house in relation to his own mortality:

Clearly what haunts Scannell is a fear of death akin to Larkin’s in ‘Aubade’. Scannell links his impending death to the house that will outlast him, and which represents what it means to be alive: the familiar domestic space that provides a context for his life. Because a house is made of stone, it ‘will neither know nor care’ about his demise, but from the human perspective it’s imbued with emotional weight, given meaning by his existence, like his own flesh and blood; thus the idea of a home being empty after death augments the fear of loss and oblivion (‘Not to be here,/Not to be anywhere’, as Larkin puts it). Elsewhere, such safe spaces are seen to be under threat, their status as safe havens undermined by conflict and darkness, as in the ironically titled ‘Safe Houses’, where bad news encroaches on the domestic sanctuary of the home, interrupting the ‘Scent of coffee and the radio’s/smoothly laundered voice’:

And here it comes: a car-bomb in Baghdad kills forty-three; a sixteen-year-old lad shoots woman constable dead; Keele student raped and strangled in her room; Russian miners’ workplace now their tomb; Leeds pensioner stabbed in bed.This litany of horrors haunts the speaker, despite his efforts to rationalise and make them safe, as suggested in the closing stanza:

And later in the morning, when he goes along his quiet road to church, he knows he won’t be mugged or shot; but as he smiles, from somewhere out of sight he hears the low and ominous growl which might be thunder, or might not.It’s said that Scannell was drawn to poetry after reading Walter de la Mare, and it’s easy to see similarities in style – both have a penchant for dramatic monologues for instance – but de la Mare often feels rather distant from his verse, whereas Scannell’s life and personality are frequently manifest. During the War, Scannell saw significant action, was shot in both legs while on patrol in France, and it doesn’t take a psychiatrist to locate the origin of the fear and paranoia discernible in ‘Safe Houses’. There’s frequently a ‘low and ominous growl’ in his work, which regularly builds to a dramatic climax. This can be seen particularly in poems which reference war directly, such as ‘A Few Words to the Not-So-Old’, which closes:

But certain memories will never die: Tom Fenton’s smile, part naughty urchin’s grin yet just a little sad, before the bomb blew it and him star-high near Mareth as our Company moved in and the universe went mad.It’s fair to say that Scannell’s sense of the universe as a ‘mad’ never completely left him. As Brownjohn says in his introduction, ‘The passing of time has done little or nothing to reduce the pain of having had to live through the experience of war’. The pain is writ large throughout much of his work, and he doesn’t spare us the details, as in war poems like ‘Robbie’ where the eponymous hero ‘Sucked on his rifle-muzzle like a straw’ and blew his brains out, or in a boxing poem like ‘It Should Be Easier’, which ends,

It didn’t get easier for Scannell, as these later poems attest; he is still, to use Carey’s words, ‘haunted by memory’, but this very often provides an edge – an authority and authenticity – that adds weight to his ostensibly light verse, making for an absorbing book that I read with great pleasure.