Poetry review – HI-VIZ: James Roderick Burns finds real depth beneath Ben Banyard’s light-touch observations

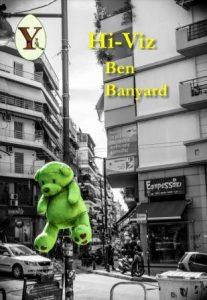

Hi-Viz

Ben Banyard

Yaffle Press, 2021

ISBN 9781913122256

56 pp £10.00

Hi-Viz

Ben Banyard

Yaffle Press, 2021

ISBN 9781913122256

56 pp £10.00

As its title suggests, Hi-Viz jumps right into the action in bright, bold colours, dissecting the ennui of the global industrial (or possibly post-industrial) age with punchy, knowing strokes, as well as vivid splashes of wit. The ‘Catch’, these days, for instance, is fairly typical:

Skinless and boneless in tin,

not what the bear juggles

for fun on the bank,

or teeming silver

in the trawler’s decked nets.

The view from a friend’s hospital room (rendered interestingly as poetic prose rather than in his usual economical free verse) is dismayingly familiar, even down to the sterile surprises of the architecture:

There’s a low window which gapes incredulously at concrete slabs with weeds oozing

between them, a bare tree, an after-thought of grass

(‘Neutropenic’).

We are in the territory of the pound shop, the packaged stag-do, chip shop and crematorium and downbeat office; ‘Since 1976’ might be the only poem in history to make effective use of GDPR, and ‘Historic Market Town’ could be unique in deploying every possible angle on a place abhorred by the tourist board:

There’s a family butcher’s which smells of bleach,

homeware store whose plastic tat froths across

the pavement, a multi-coloured obstacle course …

we swallow our pride, sidle past

six tables of drunk women and dazed toddlers

trading insults on the pretext of a baby shower.

Banyard doesn’t seem to set out to pick out the worst aspects of small-town culture – limited horizons, stunted prospects or the compensations of drink and cheap entertainment – but finding them all about, digs deep for meaning, and discovers it. The night time stars of ‘Red Carpet Street’, for instance, are not deluding themselves as they Laurel-and-Hardy away from the off-licence, or posture like Pacino outside the chip-shop. Rather, they find style and substance in the ordinary, transforming what might feel humdrum into something vibrant and powerful. The poet also locates great dignity in the scene, when evening’s glamour wears off and a harsher day dawns:

Hoffman and Lassie bed down

in the doorway of the pound shop,

a duvet and each other for warmth.

At first light they change back

into scaffolders, brickies, nurses,

half an office of mortgage brokers,

an old man and his dog with a scrap of hope.

It is a fine, lilting line, showing the care with which Banyard approaches his material. There is also more to the collection than these lively working class streetscapes. Many poems find warmth and connection in small, intimate family scenes; in the moments of transition, from singledom to relationship to parenthood; from life into death, and the spaces within which we all must navigate these things. In describing the new learner driver’s fears, for instance, he moves effortlessly into the deeper concerns which underpin his new duties:

You’ll find you can drive to the seaside,

reverse into cars at the supermarket,

notice that even with a satnav you still get lost

and crawl along in terror when you bring

two babies home from hospital as though

the boot is full of a thousand eggs.

(Slow: Learner)

It is an effective technique. Often, the poet yokes together acid observations (pithily expressed) with the softer underbelly of a situation, where we frequently find pathos or humour to lighten the effect: while the ‘Worshippers’ of Majorca “steep [their] bodies in hard-earned rays”, “reptile couples basting leathered hides”, the sun itself “counts towels on loungers/to decide whose shoulders/it will kiss first each morning”. Or placing his hand on his son’s chest after a marathon exercise session, Banyard feels “Beneath the breast bone/a trapped mouse is throwing itself around”. It is the perfect image – bracing yet tender, apposite, fresh without any effort; arresting. In a few lines he pierces to the centre of things.

Overall, it is an impressive performance. Though the casual reader might see Banyard as the laureate of the pound shop, a promenade Larkin nailing prickly caricatures to the page (and he does flesh out Mr Bleaney from his own perspective: “Expect to unfurl for forty years or so,/then curl slowly, neatly, back on yourself”), he achieves far more than this. Blending acute social observation with unflinching realism, a search for meaning and the consistent attribution of dignity to even the most strained of settings, the poet forges his own distinct poetic milieu – Banyardland, perhaps. This reaches its greatest expression in ‘Paignton’, whose five short stanzas cinch together all the strands of the book’s accomplishments into a stirring conclusion. We all partake of the grubbiness, the compromises of life, it suggests, but in doing so we move towards something better, higher, in the end:

Families in matching anoraks

eat chips out of polystyrene trays

on benches in memory of the forgotten.

And yet we flock in thousands,

walk hand in slippery sunscreened hand,

collect sea glass to catch the light.

Apr 24 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Ben Banyard

Poetry review – HI-VIZ: James Roderick Burns finds real depth beneath Ben Banyard’s light-touch observations

As its title suggests, Hi-Viz jumps right into the action in bright, bold colours, dissecting the ennui of the global industrial (or possibly post-industrial) age with punchy, knowing strokes, as well as vivid splashes of wit. The ‘Catch’, these days, for instance, is fairly typical:

The view from a friend’s hospital room (rendered interestingly as poetic prose rather than in his usual economical free verse) is dismayingly familiar, even down to the sterile surprises of the architecture:

between them, a bare tree, an after-thought of grass (‘Neutropenic’).We are in the territory of the pound shop, the packaged stag-do, chip shop and crematorium and downbeat office; ‘Since 1976’ might be the only poem in history to make effective use of GDPR, and ‘Historic Market Town’ could be unique in deploying every possible angle on a place abhorred by the tourist board:

Banyard doesn’t seem to set out to pick out the worst aspects of small-town culture – limited horizons, stunted prospects or the compensations of drink and cheap entertainment – but finding them all about, digs deep for meaning, and discovers it. The night time stars of ‘Red Carpet Street’, for instance, are not deluding themselves as they Laurel-and-Hardy away from the off-licence, or posture like Pacino outside the chip-shop. Rather, they find style and substance in the ordinary, transforming what might feel humdrum into something vibrant and powerful. The poet also locates great dignity in the scene, when evening’s glamour wears off and a harsher day dawns:

It is a fine, lilting line, showing the care with which Banyard approaches his material. There is also more to the collection than these lively working class streetscapes. Many poems find warmth and connection in small, intimate family scenes; in the moments of transition, from singledom to relationship to parenthood; from life into death, and the spaces within which we all must navigate these things. In describing the new learner driver’s fears, for instance, he moves effortlessly into the deeper concerns which underpin his new duties:

You’ll find you can drive to the seaside, reverse into cars at the supermarket, notice that even with a satnav you still get lost and crawl along in terror when you bring two babies home from hospital as though the boot is full of a thousand eggs. (Slow: Learner)It is an effective technique. Often, the poet yokes together acid observations (pithily expressed) with the softer underbelly of a situation, where we frequently find pathos or humour to lighten the effect: while the ‘Worshippers’ of Majorca “steep [their] bodies in hard-earned rays”, “reptile couples basting leathered hides”, the sun itself “counts towels on loungers/to decide whose shoulders/it will kiss first each morning”. Or placing his hand on his son’s chest after a marathon exercise session, Banyard feels “Beneath the breast bone/a trapped mouse is throwing itself around”. It is the perfect image – bracing yet tender, apposite, fresh without any effort; arresting. In a few lines he pierces to the centre of things.

Overall, it is an impressive performance. Though the casual reader might see Banyard as the laureate of the pound shop, a promenade Larkin nailing prickly caricatures to the page (and he does flesh out Mr Bleaney from his own perspective: “Expect to unfurl for forty years or so,/then curl slowly, neatly, back on yourself”), he achieves far more than this. Blending acute social observation with unflinching realism, a search for meaning and the consistent attribution of dignity to even the most strained of settings, the poet forges his own distinct poetic milieu – Banyardland, perhaps. This reaches its greatest expression in ‘Paignton’, whose five short stanzas cinch together all the strands of the book’s accomplishments into a stirring conclusion. We all partake of the grubbiness, the compromises of life, it suggests, but in doing so we move towards something better, higher, in the end: