Poetry review – ALL THE MEN I NEVER MARRIED: Carla Scarano reviews a collection of challenging and personal poems by Kim Moore

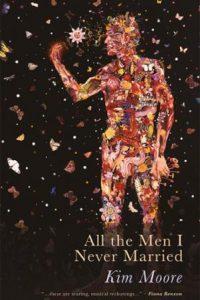

All the Men I Never Married

Kim Moore

Seren Books

ISBN 9781781726419

£9.99

All the Men I Never Married

Kim Moore

Seren Books

ISBN 9781781726419

£9.99

Kim Moore’s brave and honest poems engage the reader in a comprehensive feminist vision that challenges the roles assigned to women in a dominantly patriarchal society and exposes the contradictions and violence in such a society. The collection’s 48 poems sharply and insightfully trace the traumas, constraints and abuse the average woman undergoes from childhood to womanhood. Moore emphasises states of anxiety and guilt and an unsettling sense of estrangement from herself. The body speaks its own language, the language of desire, in an attempt to reconstruct the shattered self, which is confused by the everyday sexism and menaced by implicit or explicit threats made to women by men. The vulnerability of desire has dangerous implications in a man’s world where women are used and abused and their physicality is reduced to objectification.

Moore is based in the north-west of England. Her first full collection, The Art of Falling (Seren Books, 2015), is deeply rooted in her territory and is connected with her people. They are ordinary people ‘who swear without realising they are swearing’ and include ‘a line of women who bring up children and men who go to work’ (‘My People’, The Art of Falling). It also features a compelling sequence about an abusive relationship and the protagonist’s struggle to break free, a topic she develops further in her second collection, All the Men I Never Married, which has a wider breadth. The structure of the poems and the concepts that are elaborated connect to the personal and also to what happens in the actual world in a broader and universal perspective.

Moore also links her thought to the tradition of feminist writing, for example to Virginia Wolf and to Adrienne Rich, and, above all, to Hélène Cixous. These writers struggled to find their voices in a man’s world in which they are told what to say and think and how to behave:

where we are told to keep our legs closed,

where we sat in the light of a window and posed

and waited for the makers of the world

to tell us again how a woman is made.

Even the language they use is the language of men and, as Cixous remarks, in order to rediscover their inner self, women must write from their bodies from which they have become estranged. Their sexual pleasure has been silenced and denied, and to regain power they need to connect with their body in a free, unrestrained way. It is a complex, long process that needs constant self-interrogation as well as witnessing. Moore’s writing from the body is revolutionary and provocative:

[…] When I think

of your voice, my soul drifts downwards inside my body

like a leaf falling side to side through the air.

The poems are not titled but simply numbered and the above quote is from “14”. Poem “15” includes the lines

[…] I thought sex was a promise

that would keep being fulfilled, I thought love was a knife

pressed to the throat. I thought there was a blade

in each of our hands. I am telling this now so he appears,

as real as that first night when he didn’t sleep.

And here is an extract from “25”.

When I tell them about my body

and all the things it knows

they tell me about their guilt

they flourish their guilt

as if they are matadors

in a city where people love blood

Moore finds her voice as a woman and attempts to invert the gaze; she is a woman who looks at men, speaks of men, experiences men. Her poignant and often dramatic stories describe how things are in an apparently objective way without making statements or judgements. Thus, her powerful practice of storytelling unravels the ambivalence of the roles assigned to women in society using a method of showing rather than telling. In her stories, women struggle to break free from a mental dependence on men who shape their lives and subdue their bodies. They are reduced to nothing, split between body and heart by destabilising forces of violence and desire, as is quoted in the epitaph. It is a game of gain and loss in which the risk of abuse and rape constantly emerges because ‘being in public is a dangerous thing’ and ‘our bodies are dangerous things.’

Moore is a master of repetition, especially anaphora and epistrophe, which create an enthralling impeccable rhythm; they allow a deeper exploration of her arguments and provoke the reader in a spiral of self-awareness urging change:

now I’ve said the word whisper it rape,

now I’ve said the word whisper it shame,

will my true ones, my wild, my truth,

will my wild come back to me again?

(“43”)

I let a man into my body and let him sleep

inside my room. I let him in, I let him in,

I said that he could do those things

but only in my mind. I let a man

into my room and took a vow of silence,

took a vow of there’s no turning back,

because a mind is not for changing.

(“46”)

The poems speak of ‘transformation and violence and loss’ but also of the magic of being in a fulfilling relationship that makes us human. A sense of tenderness or longing for a romance of sorts reveals a profoundly empathetic side in Moore’s poems that counterbalances the stark descriptions of domestic violence and abuse. This opens up to hope and possible changes that nevertheless require a constant witnessing in a state of alert and fear of backlashes.

The themes of nothingness and violence against women also refer to works such as King Lear and Othello as well as to ancient myths, especially to the stories of Zeus’s rapes of Leda, Europa and Danae, which are revisited by Moore from an ordinary perspective. The god is ‘just a man / like and unlike any other’ and ‘no wife turned up/to take revenge / to transform me into a cow’. However, the abuse is present, just as it is in the myth, and it causes self-effacement and permanent trauma. Moore’s collection hits all the right notes in a wide-ranging view that is both lyrical and actual, as well as relevant to our time. It has that dreamlike quality, which good poetry often has, involving the reader in an imaginary world that is also the world we experience, challenging and reversing common views. Her vision is therefore incisive and crisp and invites us to act and to voice who we are.

Nov 26 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – Kim Moore

Poetry review – ALL THE MEN I NEVER MARRIED: Carla Scarano reviews a collection of challenging and personal poems by Kim Moore

Kim Moore’s brave and honest poems engage the reader in a comprehensive feminist vision that challenges the roles assigned to women in a dominantly patriarchal society and exposes the contradictions and violence in such a society. The collection’s 48 poems sharply and insightfully trace the traumas, constraints and abuse the average woman undergoes from childhood to womanhood. Moore emphasises states of anxiety and guilt and an unsettling sense of estrangement from herself. The body speaks its own language, the language of desire, in an attempt to reconstruct the shattered self, which is confused by the everyday sexism and menaced by implicit or explicit threats made to women by men. The vulnerability of desire has dangerous implications in a man’s world where women are used and abused and their physicality is reduced to objectification.

Moore is based in the north-west of England. Her first full collection, The Art of Falling (Seren Books, 2015), is deeply rooted in her territory and is connected with her people. They are ordinary people ‘who swear without realising they are swearing’ and include ‘a line of women who bring up children and men who go to work’ (‘My People’, The Art of Falling). It also features a compelling sequence about an abusive relationship and the protagonist’s struggle to break free, a topic she develops further in her second collection, All the Men I Never Married, which has a wider breadth. The structure of the poems and the concepts that are elaborated connect to the personal and also to what happens in the actual world in a broader and universal perspective.

Moore also links her thought to the tradition of feminist writing, for example to Virginia Wolf and to Adrienne Rich, and, above all, to Hélène Cixous. These writers struggled to find their voices in a man’s world in which they are told what to say and think and how to behave:

Even the language they use is the language of men and, as Cixous remarks, in order to rediscover their inner self, women must write from their bodies from which they have become estranged. Their sexual pleasure has been silenced and denied, and to regain power they need to connect with their body in a free, unrestrained way. It is a complex, long process that needs constant self-interrogation as well as witnessing. Moore’s writing from the body is revolutionary and provocative:

The poems are not titled but simply numbered and the above quote is from “14”. Poem “15” includes the lines

And here is an extract from “25”.

When I tell them about my body and all the things it knows they tell me about their guilt they flourish their guilt as if they are matadors in a city where people love bloodMoore finds her voice as a woman and attempts to invert the gaze; she is a woman who looks at men, speaks of men, experiences men. Her poignant and often dramatic stories describe how things are in an apparently objective way without making statements or judgements. Thus, her powerful practice of storytelling unravels the ambivalence of the roles assigned to women in society using a method of showing rather than telling. In her stories, women struggle to break free from a mental dependence on men who shape their lives and subdue their bodies. They are reduced to nothing, split between body and heart by destabilising forces of violence and desire, as is quoted in the epitaph. It is a game of gain and loss in which the risk of abuse and rape constantly emerges because ‘being in public is a dangerous thing’ and ‘our bodies are dangerous things.’

Moore is a master of repetition, especially anaphora and epistrophe, which create an enthralling impeccable rhythm; they allow a deeper exploration of her arguments and provoke the reader in a spiral of self-awareness urging change:

now I’ve said the word whisper it rape, now I’ve said the word whisper it shame, will my true ones, my wild, my truth, will my wild come back to me again? (“43”) I let a man into my body and let him sleep inside my room. I let him in, I let him in, I said that he could do those things but only in my mind. I let a man into my room and took a vow of silence, took a vow of there’s no turning back, because a mind is not for changing. (“46”)The poems speak of ‘transformation and violence and loss’ but also of the magic of being in a fulfilling relationship that makes us human. A sense of tenderness or longing for a romance of sorts reveals a profoundly empathetic side in Moore’s poems that counterbalances the stark descriptions of domestic violence and abuse. This opens up to hope and possible changes that nevertheless require a constant witnessing in a state of alert and fear of backlashes.

The themes of nothingness and violence against women also refer to works such as King Lear and Othello as well as to ancient myths, especially to the stories of Zeus’s rapes of Leda, Europa and Danae, which are revisited by Moore from an ordinary perspective. The god is ‘just a man / like and unlike any other’ and ‘no wife turned up/to take revenge / to transform me into a cow’. However, the abuse is present, just as it is in the myth, and it causes self-effacement and permanent trauma. Moore’s collection hits all the right notes in a wide-ranging view that is both lyrical and actual, as well as relevant to our time. It has that dreamlike quality, which good poetry often has, involving the reader in an imaginary world that is also the world we experience, challenging and reversing common views. Her vision is therefore incisive and crisp and invites us to act and to voice who we are.